Pacific leaders called for binding climate obligations, Pacific-led finance mechanisms, and reforms that give small states real influence.

Photo/PMN

UN must adapt to Blue Pacific, not the other way around - leaders

Pacific leaders took the 2050 Strategy to the UN, calling for climate justice, fair finance, and security defined by peace and solidarity.

Christchurch Polyfest celebrates 25 years of Pacific culture in NZ

Food, music, culture return as Pasifika Festival takes over Western Springs

Six in 10 Pacific families struggling to afford food, new report finds

Christchurch Polyfest celebrates 25 years of Pacific culture in NZ

Food, music, culture return as Pasifika Festival takes over Western Springs

Pacific Island leaders addressed the United Nations General Assembly’s (UNGA) 80th session in New York, demanding urgent climate action, fairer finance, and reforms to give small states real power.

From Palau to Kiribati, New Zealand to Tuvalu, representatives struck different tones, but one message was clear: climate change remains the region’s greatest existential threat, and the international community, through multilateral systems, must answer the call for help.

At the UNGA, Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) members presented the 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent and its first Implementation Plan (2023-2030), delivering a unified call for climate justice, resilience, ocean stewardship, and multilateral reform.

The loudest message was climate change. Notably, leaders shifted from pleading for empathy to wielding the authority of international law after the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea issued advisory opinions treating climate action as a binding duty.

Solomon Islands’ Prime Minister and current chairperson of PIF, Jeremiah Manele says “the court has made clear that states carry binding obligations to act on climate change… these duties are legal, moral, and universal.” Sāmoa’s Deputy Prime Minister, Toelupe Poumulinuku Onesemo, called for a 50 per cent cut in global emissions by 2030, saying “climate change is our lived reality, not an abstract debate”.

Vanuatu’s Ambassador to the UN, Odo Tevi, reinforced this shift, noting that his nation led the UN initiative requesting the ICJ advisory opinion and is now moving to operationalise its findings with a follow-up resolution.

Prime Minister of the Solomon Islands, Jeremiah Manele, is also the chairperson of the Pacific Islands Forum. Photo/UN Photo/Loey Felipe

He joined calls to recognise “ecocide” as an international crime, arguing that preventing environmental destruction is as vital as adaptation and mitigation. Tevi highlighted repeated cyclones and a 2024 earthquake, while foreign blacklisting and banking restrictions continue to choke access to finance.

As one of the world's smallest, low-lying countries, Tuvalu acutely feels the existential crisis threatening its people.

Prime Minister Feleti Teo outlined five avenues to support a looming 2026 UN declaration on sea-level rise: statehood continuity, mobility with dignity, cultural protections, rapid finance, and science and data access.

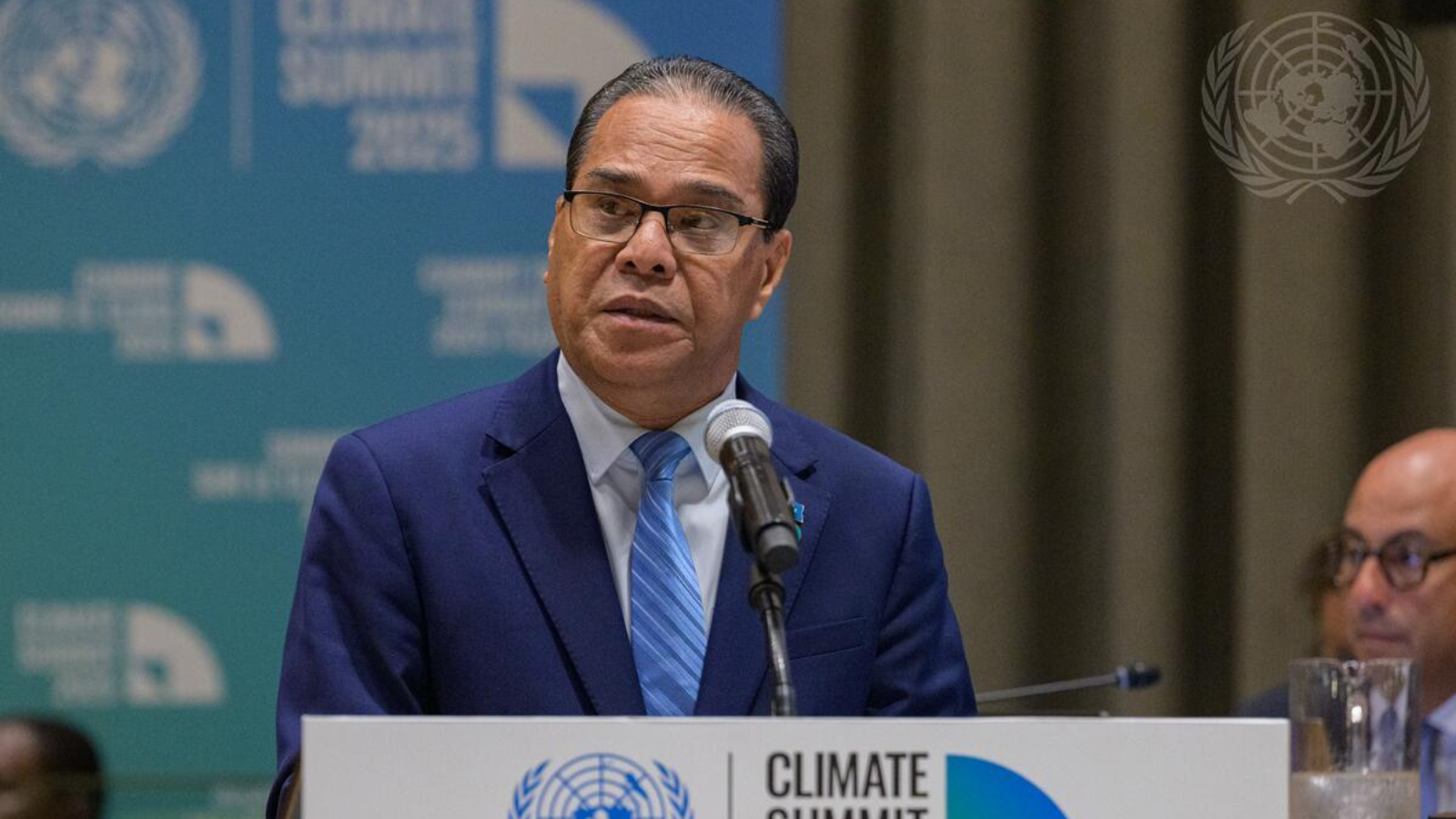

Prime Minister Feleti Teo speaks of Tuvalu's climate change crisis. Photo/Manuel Elias

“Tuvalu has amended its constitution to ensure Tuvalu's statehood in perpetuity, and its maritime boundaries are protected and remain permanent, no matter what happens to Tuvalu's land territory because of climate change,” Teo says.

The President of the Marshall Islands, Hilda Heine, used her address to revisit past injustices, namely the 67 US nuclear tests carried out under UN trusteeship, connecting them to the climate crises of today.

“My low-lying atoll nation bears witness to the sharpest edge of climate change… we need the world to better understand that our security is linked to our fragility cutting across key indicators.

President Hilda Heine greets UN Sec-Gen Antonio Gutteres in New York. Photo Eskinder Debebe

“Perhaps, after 34 years since our admission, the UN can finally bring healing and closure over decisions which never should have been made,” Heine says.

Amid legal and diplomatic pressure, leaders expressed frustration over unmet financial promises. Pledges without access matter little.

The Pacific Resilience Facility (PRF) is a Pacific-owned, led, and designed funding mechanism under PIF that was put forth as a solution.

Tonga, as host to the facility, called it a “Pacific-led mechanism to bridge the gap.” Nauru called it an “investment in stability, not charity”. Solomon Islands’ PM Manele announced a $860 million target by next year.

At a PRF Partners Talanoa last week at the UN headquarters, a capitalisation memorandum for investors was launched. This officially opened the door to pledges from now until December 2026. Pledges from Ireland ($6 million), Portugal ($2 million), and Germany ($10 million) at the Partners Talanoa brings the current total to $286 million.

Equally prominent in the leaders’ statements was the Multidimensional Vulnerability Index (MVI), a tool showing how structural weaknesses and resilience gaps shape sustainable development. Leaders from Fiji, Nauru, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Kiribati demanded its operationalisation.

A new vulnerability index will better support efforts to strengthen sustainable development initiatives. Photo/Anetone Sagaga

The Prime Minister of Fiji, Sitiveni Rabuka, told the assembly that for Fiji, the MVI is a matter of development justice.

President of Nauru, David Adeang, called for it as the new benchmark for concessional finance, warning that GDP figures hide the fragility of small states.

Samoa said the Seville Compromise on development financing was a “missed opportunity.”

The Marshall Islands’ Heine was blunt: “Promises don’t reclaim land in atoll nations like mine.”

The ocean was another recurring theme. Leaders universally backed the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction Agreement (BBNJ), often referred to as the ‘high seas treaty’, which is an agreement that is set to become effective in 2026.

The treaty calls for an urgent response to harmful actions, such as pollution and the unsustainable use of marine resources. In this context, Kiribati’s President Taneti Maamau estimated that IUU (illegal, unreported, unregulated) fishing costs Pacific nations over $1 billion every year, calling it a “moral and economic injustice”.

Watch Kiribati's country statement at UNGA80

There is no consensus on deep-sea mining, with Palau, Tuvalu, the Marshall Islands, and Solomon Islands supporting a moratorium or scientific approach.

Palau’s President Surangel Whipps, Jr. warned, “If we rush forward without understanding the consequences, we risk inflicting irreparable harm”. Nauru defended sponsoring seabed mineral exploration under the International Seabed Authority, insisting these minerals are "vital for the renewable energy transition." Nauru called the criticism unfair and argued that strong regulations, and not delay, are the responsible path.

This split revealed a weakness in Pacific solidarity and raised questions about how to balance urgent climate finance with Blue Pacific stewardship.

Several leaders invoked the Ocean of Peace Declaration, a regional initiative adopted by PIF leaders earlier in September. Broadly, it envisions a peaceful, secure, and harmonious Pacific. At the UN, leaders reframed regional security as stewardship and solidarity, not a tussle between larger powers.

Fijian Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka connected it to the Pacific Way of reconciliation, recalling 45 years of Fijian UN peacekeeping and his own military service. “Peace is the starting point… the Pacific knows its value having lived through its absence.”

Micronesian President Wesley Simina connected the Ocean of Peace vision to nuclear legacies that continue to affect the country. He referred to an oil leak from a sunken WWII US vessel in Truk Lagoon.

The leader of the Federated States of Micronesia, Wesley Simina, says wartime wrecks in their waters pose new dangers as toxic oil spills threaten livelihoods. Photo/UN Photo/Manuel Elias

“This ship, together with more than 60 other wartime wrecks, has rested in our waters for nearly 80 years since the war’s end. But now, these remnants of conflict pose new dangers as toxic oil seeps into our oceans, threatening our fishers, coastal communities, and livelihoods.”

Tonga’s Prime Minister, ‘Aisake Valu Eke, called the declaration “more than symbolism”, stressing its role in amplifying Pacific voices at the UN.

“If the UN is to deliver for our people, it must deliver with us, through us.”

On geopolitical issues, Pacific leaders differed on development partnerships and global conflicts. Ahead of the recent PIF leaders’ meeting, divisions between countries recognising China or Taiwan also played out in their positions at UNGA80.

Nauru and the Solomon Islands stood firm on the One China principle. At the same time, Palau, Tuvalu, and the Marshall Islands openly supported Taiwan’s participation in the UN system, accusing China of misusing Resolution 2758 to silence an entire people.

“Palau believes that inclusivity, which includes Taiwan, strengthens the United Nations, and that no community should be barred from contributing to the solutions of our world,” President Whipps told the UNGA.

Watch Nauru's country address at the UNGA80 below

Nauru’s President Adeang, says China’s partnership has contributed “meaningful opportunities for infrastructure, trade, and development that support Nauru’s progress”.

For Australia and New Zealand, both members of the PIF, their paths diverged on Palestine.

PM Anthony Albanese positioned Australia as an activist middle power, recognising Palestinian statehood and bidding for a UN Security Council seat in 2029-2030. New Zealand’s Foreign Affairs Minister, Winston Peters, argued that early recognition of the territory could "strengthen both Hamas and Israeli hardliners."

“Palestine does not fully meet the accepted criteria for a state, as it does not fully control its own territory or population,” he told the general assembly.

“There is also no obvious link between more of the international community recognising the state of Palestine and the aimed objective of protecting the two-state solution,” says Peters, who also announced a financial contribution to support the humanitarian crisis in Gaza.

Papua New Guinea’s Prime Minister, James Marape, presented his nation as a model of ‘peace through dialogue’, shown by the Bougainville Peace Agreement. He urged warring parties to “give peace a go.”

Watch NZ Foreign Affairs Minister Winston Peters at the UNGA80

Marape also pressed industrial nations to compensate forest and ocean states, such as PNG, which absorb more carbon than they emit.

Across the region, leaders emphasised the importance of sovereignty in the face of sea-level rise.

Tuvalu, Kiribati, and Solomon Islands each highlighted that maritime boundaries and statehood must remain permanent.

“Even if rising seas inundate our islands, our statehood and maritime boundaries will endure,” PM Manele says.

Tuvalu’s constitutional amendment and its treaty with Australia, the Falepili Union, were held up as pioneering steps to guarantee continuity and mobility “with dignity.”

Kiribati’s President Maamau rejected the narrative of “sinking islands,” stressing adaptation through both traditional and modern strategies.

The Marshall Islands, still scarred by nuclear testing, called for closure and accountability from the UN itself, saying small nations deserve justice not just for climate but for historical harms.

President Heine pointed out that a legacy of 67 atmospheric nuclear tests between 1946 and 1958 includes significant disagreements, including responsibility for what remains for the Marshallese today.

“Our communities seek justice, a clean environment, and safe return to their homes,” Heine says.

“Seventy-nine years after the first nuclear test was conducted in my country in 1946, the UN should now be capable of delivering a contemporary acknowledgement and apology for what took place in its name and under its flag.”

Samoa was represented at the UNGA80 by Deputy Prime Minister Toelupe Poumulinuku Onesemo. Photo/UN Photo/Laura Jarriel

Away from climate interventions, leaders also highlighted crises of human development.

Health issues such as non-communicable diseases were described as a regional epidemic by the Marshall Islands, Fiji and Micronesia. Samoa commented on the burden of disasters and debt on health systems.

Fiji highlighted transnational drug trafficking as a rising threat; an issue intimately tied to the methamphetamine crisis in the country and in the neighbouring countries of Tonga and Samoa. Micronesia and Palau both flagged cyber and AI governance, with Micronesia co-sponsoring the first-ever UN resolution on Artificial Intelligence.

These issues are directly tied to the 2050 Strategy’s theme of People-Centred Development and to the Implementation Plan’s actions on health security, technology, and inclusion.

Nearly all of the UNGA country statements referred to the UN80 Initiative, a new process launched in March this year, touted as ‘a system-wide push to streamline operations, sharpen impact and reaffirm the UN’s relevance for a rapidly changing world’.

Tonga and Samoa argued that the UN80 Initiative must align with the Pacific’s 2050 Strategy and not duplicate or undermine regional architecture.

UN Sec-Gen meets with leaders from the Pacific at the 80th session of the general assembly. Photo/UN Photo/Evan Schneider

The Solomon Islands and Micronesia called for a reform of the UN Security Council, with Micronesia backing new permanent seats for Japan, India, Brazil, Germany, and Africa.

The Pacific’s 2050 Strategy sets out a vision for peace, security, and prosperity. The Implementation Plan calls for strengthening architecture, securing finance, embedding culture, and building resilience.

At UNGA80, the Pacific did not just plead for survival; it set out a blueprint, backed by law, finance, and regional strategy, demanding that the UN system adapt to the Blue Pacific, not the other way around.