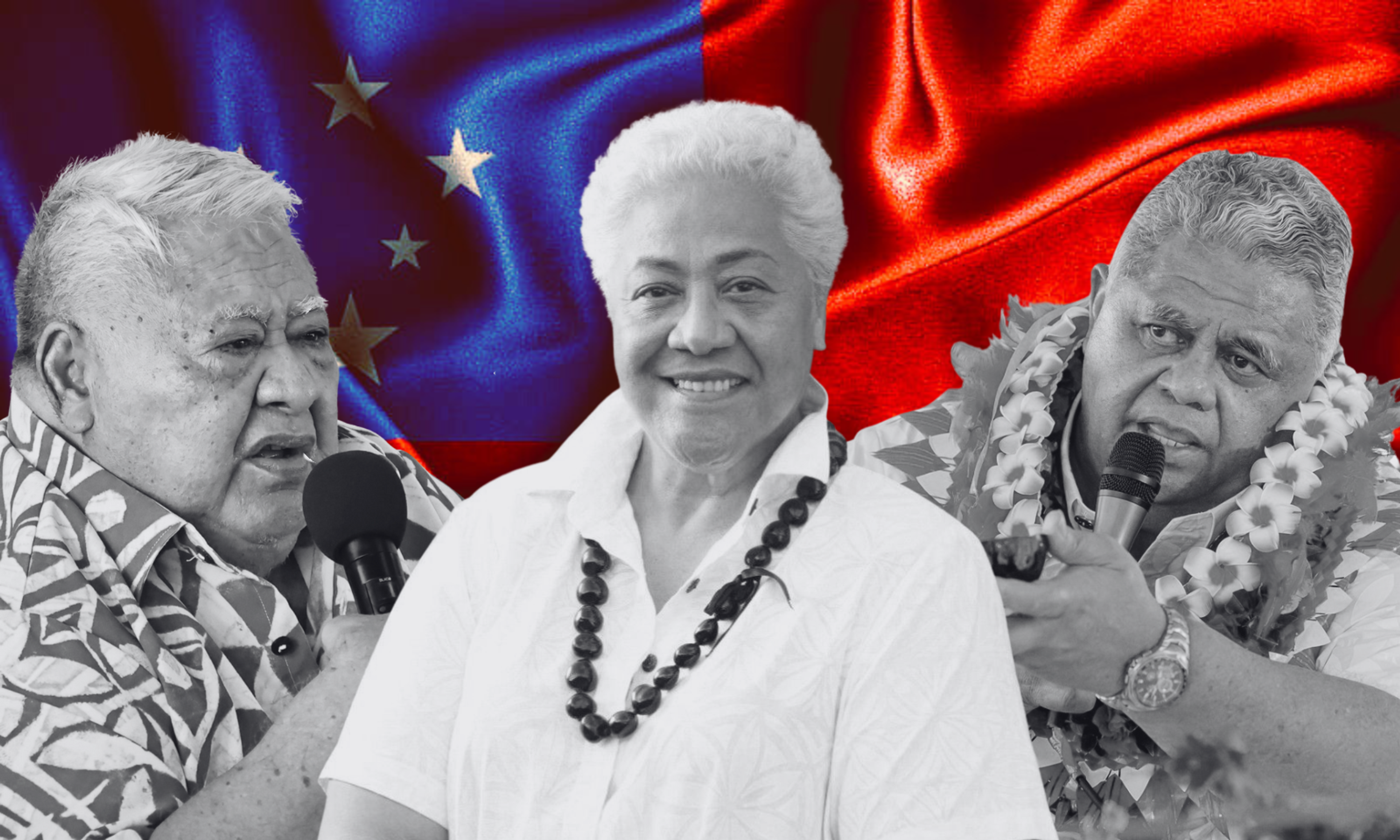

Who will hold the power after Sāmoa's election on 29 August? It is a battle between three major players - Tuila'epa, Fiamē, and Laauli..

Photo/PMN

All you need to know about the Sāmoa 2025 general elections

In the first of a two-part series, PMN News Senior Reporter Renate Rivers explains who the key players are, the issues, and voting process of this election.

Peters backs visa reforms for Pacific nationals ahead of petition handover

From development squad to World Series: Teenager earns Black Ferns Sevens contract

Peters backs visa reforms for Pacific nationals ahead of petition handover

On 29 August, Sāmoans will go to the polls to elect their parliamentary representatives for the next five-year term.

This guide provides an overview of Sāmoa’s government, the main political players, and the contentious issues of the upcoming election.

In May, Prime Minister Fiamē Naomi Mataʻafa’s minority government was unable to secure parliamentary support for its 2025/2026 budget, prompting her to seek a dissolution of Parliament.

The budget defeat followed months of political turmoil. Fiamē and several MPs split from their ruling party, Fa’atuatua i le Atua Sāmoa ua Tasi (FAST), due to internal disputes over her leadership and police charges against FAST Chair Laaulialemalietoa Leuatea Polataivao Schmidt.

After a cabinet culling and reshuffle, and failed attempts at inter-party negotiations, Laaulialemalietoa expelled Fiamē and five Cabinet ministers from FAST, effectively creating a third, unofficial bloc in Parliament - a minority government led by Fiamē.

On 25 February, the opposition Human Rights Protection Party (HRPP) introduced a no-confidence motion against Fiamē, which failed with a vote of 34-15. Notably, FAST voted against the motion despite publicly declaring no confidence in the Prime Minister.

Prime Minister Fiamē Naomi Mata'afa is facing one of the toughest challenges in her political career. Photo/Government of Sāmoa

Nine days later, FAST filed its own no-confidence motion, which also failed, 32-19, with HRPP voting to keep Fiamē as leader, citing unfavourable motion terms.

The twin no-confidence motions in February and March signalled the likelihood of a snap election, further fuelled by escalating tensions between Fiamē’s camp and FAST.

At the May budget session, Fiamē warned that failure to pass the bill would trigger early elections. When the bill was voted down, she confirmed that she would advise the Head of State, Tuimaleali’ifano Va’aletoa Sualauvi II, to dissolve Parliament, which came into effect on 3 June.

FAST Party leader Laaulialemalietoa Leuatea Polataivao Schmidt is welcomed at one of the district roadshows on the campaign trail. Photo/FAST

Government structure

Sāmoa operates under a parliamentary democracy that blends Westminster principles with the fa’amatai chiefly system. The unicameral Parliament has 51 seats, with a 10 per cent quota reserved for women, a constitutional amendment first introduced at the 2016 general election. Among other conditions, all MPs must hold a matai (chief) title within their districts and meet residency and monotaga (service)requirements.

The Head of State is a largely ceremonial position generally held by a paramount chief elected by parliament every five years.

The Prime Minister usually emerges from the party with majority support. Once appointed, the Prime Minister selects Cabinet ministers, typically 14, who then direct the administration and policy of the executive government.

The third branch of government, the judiciary, includes the District Court, Supreme Court, Court of Appeal, and the Land and Titles Court. The Land and Titles Court, established under Sāmoa’s Constitution, governs a legal system that is separate from civil and criminal courts. This uniquely Sāmoan judicial body has special jurisdiction on matters related to matai titles and customary lands.

On a local level, councils oversee village affairs under customary law, working alongside national governance mechanisms such as the district development committees or fono faavae, and through government-paid roles like the sui o nu’u (community liaisons).

Opposition leader and former Prime Minister Tuilaʻepa Saʻilele Malielegaoi, at a Human Rights Protection Party (HRPP) rally. Photo/HRPP

How the electoral system works

General elections are held every five years using a first-past-the-post system across 51 electoral districts in Upolu, Manono, Apolima, and Savaii. A quota ensures that at least 10 per cent of the seats are reserved for women.

Members of Parliament are elected from districts largely based on traditional village boundaries. To qualify as a candidate, individuals must meet cultural criteria, such as holding a matai (chief) title and fulfilling monotaga (community service). Candidates can run as Independents or align with a party for pre-election campaigning. Political parties must have a minimum of eight members to be officially recognised in Parliament.

Once candidate registrations are closed but before election day, challenges can be filed with the Electoral Court (the Supreme Court temporarily assigned to handle electoral cases). For the current election cycle, challenges have centred mainly on disputes over monotaga.

Post-elections, there is a period allowed under the law for petitions to challenge the winning candidates. These petitions can be lodged by the Electoral Commissioner or candidates who received at least 50 per cent of the winner’s total vote count. For example, a candidate with fewer than 50 votes cannot petition a candidate with 100 votes, but someone with 51 or more votes is allowed to do so. Petitions, and counter-petitions, generally address allegations of corrupt practices such as bribery or treating, which the law defines as when a person provides food, drink, entertainment or provision to influence a voter’s choice, induce them to vote/not to vote, or reward them for doing so. This also applies to the person who accepts the ‘treats’. If found guilty, individuals may lose their recently-won seats and could be banned from contesting for a seat for five years, which could mean missing out on the next election cycle and potentially waiting 10 years to run again.

The party that secures the majority of seats forms the government.

Who can run for office?

To contest a seat in Parliament, you must be a citizen and registered to vote in the district you wish to represent. You also need to hold a matai title from that same district and have fulfilled your monotaga for at least three years. Monotaga refers to your service or contributions to your village, church, or family - whether through active help, financial support, or other forms of assistance.

Candidates must have lived in Sāmoa for at least 10 months each year during the three consecutive years before nomination. Those who are bankrupt or have certain criminal convictions are barred from running. A key requirement for anyone employed as a public or civil servant is that they must resign from their position before registering as a candidate.

How do political parties work in Sāmoa?

Anyone can launch a political party in Sāmoa, but it gains official recognition in Parliament only after at least eight members win their district seats in an election. Once candidates declare allegiance to a party, they are required to remain with that party for the entire five-year parliamentary term.

Leaving the party mid-term will result in the seat being declared vacant and triggers a by-election. Candidates who run and win as Independents can choose to join a party or remain independent after the election. Every party must appoint a leader and a deputy and is eligible for government grants to support its activities.

The House of Parliament at Mulinu'u holds 51 seats for each of the districts across the island nation. Photo/Junior S Ami

What are the key issues in this election?

The party that wins Sāmoa’s 2025 general election will not only govern for the next five years, but it could also set the tone for politics in the country for years to come. The outcome will decide who holds the confidence of the people and who can maintain it.

FAST heads into the race weighed down by internal rifts that have split its core support. The HRPP, recovering from its 2021 defeat, has rebuilt momentum by tapping into voter frustration over FAST’s performance, while rallying a loyal base still aggrieved by the results of the last election. The Sāmoa Uniting Party (SUP) is pitching itself as a party with an unwavering respect for the rule of law, grounded in principled leadership and guided by community-based values entrenched in Sāmoan aganu’u (culture/custom).

All three parties are campaigning on similar promises to increase pensions for the elderly, enhance disability allowances, cut or remove the cost of schooling, and improve healthcare by upgrading hospitals at both national and district levels. They have also put the cost-of-living crisis at the centre of their campaigns.

The election on 29 August is a highly-contested one with three major political parties vying for control of parliament. Photo/Junior S Ami

However, they differ in how they propose to deliver economic relief:

FAST wants to raise the minimum wage to ST$6 per hour, scrap VAGST and duties on certain essentials, and lift the tax-free income threshold to ST$20,000.

HRPP is offering a ST$500 allowance to every Sāmoan each year, a five-year tax holiday for new small businesses, and a cut to the top income tax rate from 27 per cent to 25 per cent.

SUP is promising to reduce VAGST from 15 per cent to 12 per cent, remove it completely from freezer goods, scrap tax on electricity, and give a 20 per cent refund to all income taxpayers.

On the uglier side of the political games, Laaulialemalietoa is awaiting judgement on a slew of charges, including conspiracy to pervert the course of justice related to an unsolved hit-and-run case from 2021. He has also made claims on the campaign trail, connecting Fiamē to an ongoing murder case involving Sāmoan novelist and poet Sia Figiel. These accusations have been refuted by the police commissioner and Fiamē.

One issue largely missing from party manifestos is the growing methamphetamine problem. Even with a 26 per cent drop in overall crime this year, the police commissioner has called it an “epidemic” and linked it to organised crime, social harm, and violent offending.

Watch Renate Rivers' chat with Pacific Mornings' host, William Terite, on the upcoming Sāmoa general elections.