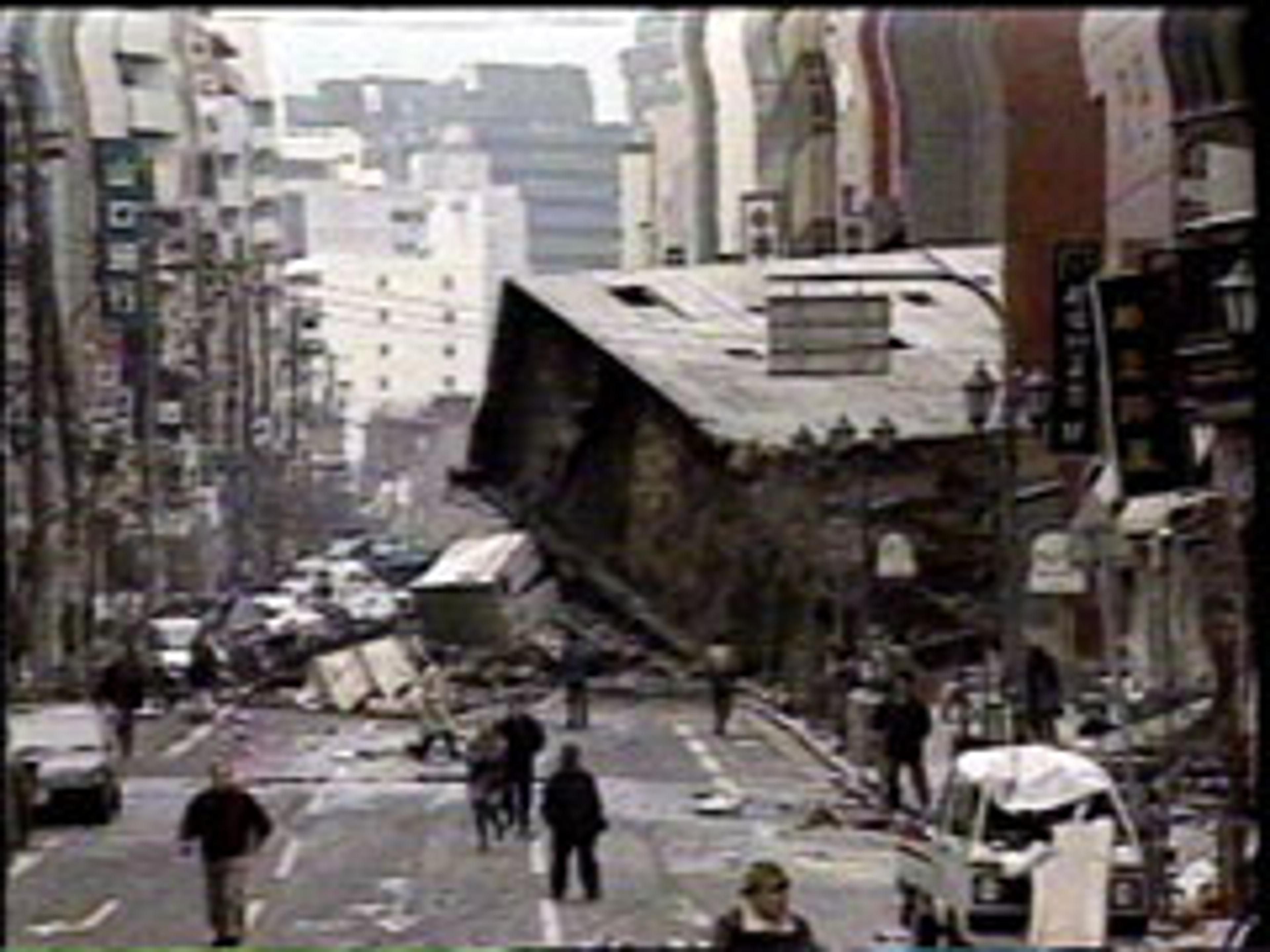

More than 170,000 buildings were destroyed during the Kobe earthquake in January 1995..

Photo/Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan

Kobe, Japan: Thirty years after the shake

Officials reflect on how tragedy shaped a city's resilience and a nation's readiness.

US funding cuts threaten to 'dry up' future of Pacific scientists - expert

Fiji’s former Prime Minister and police chief charged with inciting mutiny

Inked across lands: How Pacific tattoo art is thriving in Germany

US funding cuts threaten to 'dry up' future of Pacific scientists - expert

Fiji’s former Prime Minister and police chief charged with inciting mutiny

Early this year, exactly three decades to the day after one of the most devastating earthquakes in Japan’s modern history, snow settles quietly on the black stone of the Earthquake Memorial in Higashi Yuenchi Park in the city of Kobe.

Around a flickering remembrance flame, paper lanterns sway gently in the winter breeze, each one carrying the name of a life once lived and a memory still cherished.

It was 5.46am on 17 January 1995 when the 7.3-magnitude Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake struck Kobe in western-central Japan. Kobe is about 520km from Tokyo.

More than 6400 people lost their lives, thousands of buildings collapsed, and a community changed forever. There were no New Zealanders recorded among the victims.

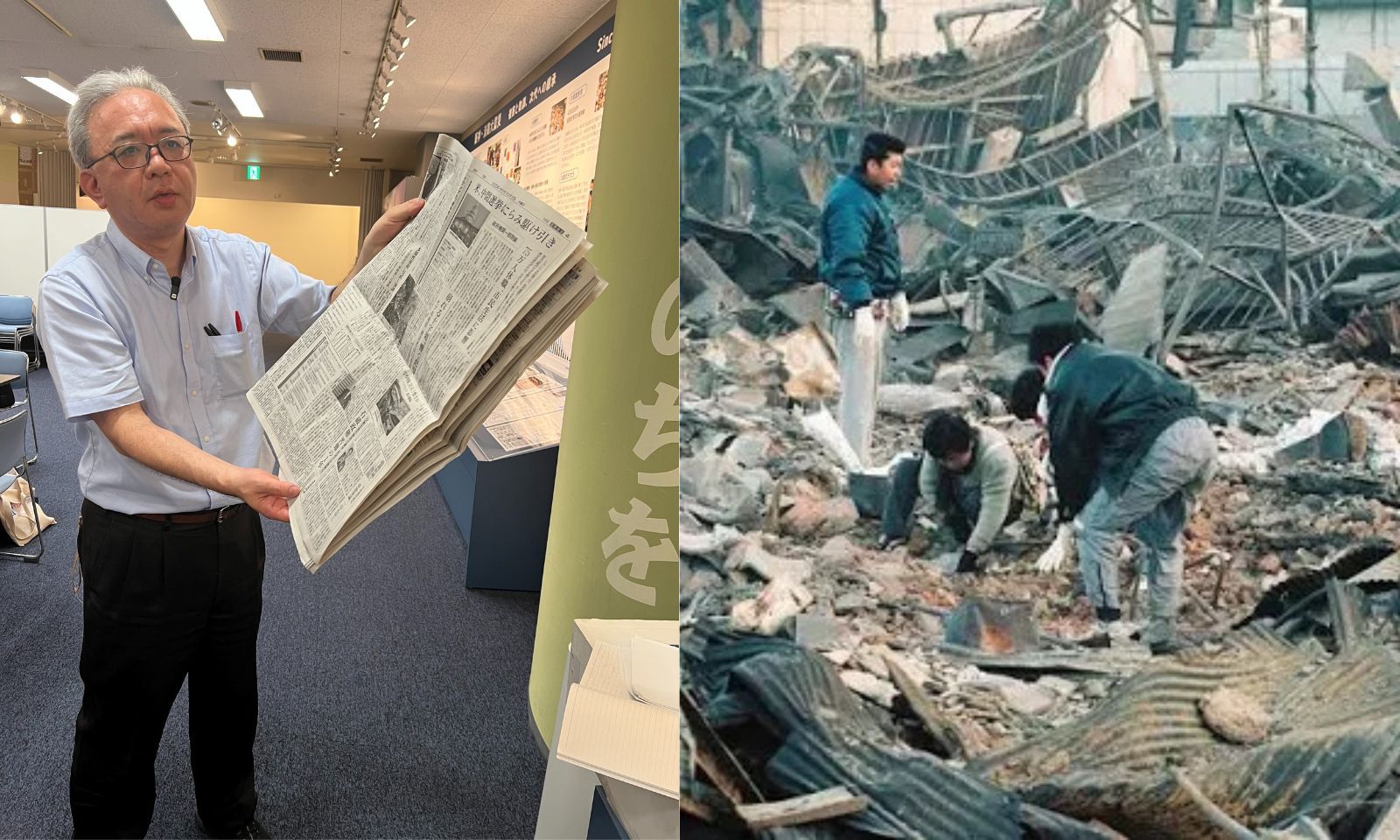

For newspaper journalist Katsunobu Ishizaki, the earthquake was more than just a news story for a budding reporter. It was the day his life and his career took a turn he never expected.

“I was in my 20s, and not long into my job at the Kobe Shimbun,” he recalls. “I thought I’d be covering city council meetings or court or something else. Instead, I was standing in front of a collapsed building, holding a notebook with shaking hands.”

Kobe Shimbun Managing Editor Katsunobu Ishizaki was in his 20s when the earthquake struck. Photo/Supplied/Kobe Shimbun

This week, at the age of 55, Ishizaki stands before a group of visiting journalists from the Pacific and Caribbean - this time by choice, not by catastrophe - to share his experience about one of the "darkest days" in Japan's history.

For 30 years, his newsroom has recorded how the city remembers, rebuilds, and learns from that tragedy.

“In those early days, everything was chaotic. Phones didn’t work, and roads were gone. We had to rely on people delivering messages on foot. I remember a woman who lost her whole family saying, ‘Please write this down. I want the world to know we existed.’ That has stayed with me.”

A school gymnasium was turned into an evacuation centre in Kobe. Photo/Supplied/Kobe Shimbun

Today, Kobe is a different city. It has been rebuilt, streets have been repaired, and neighbourhoods revitalised.

But the memories of that day still linger in the hearts of its residents. Even for those who were just children at the time, the stories have been passed down - of collapsed homes, of strangers helping strangers, of long nights without electricity or water.

For the older residents, the memories are deeply rooted in the sound of breaking concrete, the bitter cold, and the silence that followed the shaking.

In Kobe, the earthquake is historic, a living thread woven into daily life, visible in the disaster drills, reinforced buildings, and the quiet reverence with which the anniversary is observed each year.

Ishizaki feels that the earthquake shaped his career and deepened his understanding of community resilience.

“There’s a Japanese word, kizuna, that means bonds. After the quake, neighbours became like family. Strangers shared food and blankets. It showed me what real community is."

Ishizaki has also seen how journalism itself has changed. In 1995, reporters relied on old-fashioned tools like fax machines and landline phones. Today, news spreads instantly on social media, which means reporters have to act quickly but also carefully with their words and images.

“The way we report has changed so much,” he says. “We have to be fast, but we also need to be responsible. What we show and say can shape how people view a tragedy. Back then, we were the only ones sharing the news; now everyone is watching in real-time.”

The earthquake also brought about important changes in Japan’s disaster management systems, especially within the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), which monitors earthquakes and issues warnings.

At the JMA headquarters in Tokyo, Takashi Ueno discusses how the Kobe quake highlighted major gaps in their systems. He says the earthquake exposed the department's blind spots.

"We had seismometers, but no early warning system. That changed everything.”

In the years following 1995, Japan has built one of the most advanced early-warning earthquake systems in the world. Sensors placed throughout the country can detect an earthquake just seconds after it starts and can send alerts to smartphones, TVs, and speakers.

The Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake Memorial - Disaster Reduction and Human Renovation Institution in Kobe. Photo/PMN News/Christine Rovoi

“While we can’t predict earthquakes, we can definitely prepare for them,” Ueno says. “Our focus is on preventing loss of life and damage by rapidly alerting people and teaching communities how to respond.”

Since the Kobe earthquake, the JMA has worked with local governments, schools, and communities to conduct drills nationwide. Emergency kits are now common in homes and schools, and disaster preparedness is taught in their lessons.

The quake, Ueno says, has taught Japan to look at disasters as something that can happen at any time, not just as rare events.

“Every major disaster teaches us something. Kobe taught us that urban areas are not immune to these issues. That timing, early morning in winter, increased the toll. We’ve used those lessons to shape every protocol we have today.”

Both Ishizaki and Ueno were also deeply affected by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami that ravaged the Tōhoku region of northeastern Japan. But they agree that Kobe marked the beginning of Japan’s modern approach to dealing with disasters.

Every year on 17 January, as the sun rises over Kobe, volunteers extinguish the lanterns at the park as a school choir sings softly near the flame.

“We don’t come here just to mourn,” Ishizaki says. “We come to remember what we’ve learned and what we still need to do.”

Ueno and other officials at the JMA share similar thoughts. “The earth will shake again, that is certain. What matters is how ready we are, not only in terms of our systems, but also in our hearts.”

It has been 30 winters since the ground split open beneath Kobe. In that time, the city has rebuilt and adapted. But the stories of its people remain rooted in that early morning moment when everything changed.

PMN News Senior Reporter Christine Rovoi is in Japan on an Association for Promotion of International Cooperation (APIC) Japan Journalism Fellowship. During her time there, she will engage in hands-on experiences to learn about how Japan takes on challenges such as natural disasters, climate change, and sustainable living.