Photo/Screenshot/Victoria Baldwin/NZ Herald Doug Sherring

Advocates push for healing as redress debate continues for Lake Alice survivors

Tigilau Ness says recognition matters for the families as the government reveals new pay bands for victims.

Naval officers face charges over sinking of HMNZS Manawanui

Realm relations in focus as Tokelau-NZ marks 100 year history

The Sāmoan Tenor named Pati who turned disadvantage into an operatic destiny

Pacific-led building company redesigning the intergenerational housing deficit in NZ

Naval officers face charges over sinking of HMNZS Manawanui

Realm relations in focus as Tokelau-NZ marks 100 year history

The Sāmoan Tenor named Pati who turned disadvantage into an operatic destiny

Human rights advocates say the recently released redress payment bands are a step towards healing for abuse survivors, but social awareness of intergenerational trauma remains limited.

Last week, the Government confirmed compensation ranges for survivors who endured torture at the Lake Alice child and adolescent unit. Payments range from $160,000 to $600,000, depending on the severity of harm.

One of the survivors who gave evidence to the Abuse in Care Inquiry was Hakeagapuletama (Hake) Halo, a Niuean-born boy who was sent to the unit in the 1970s. At the 2021 hearing, he described the terror and agony of electric shock treatment.

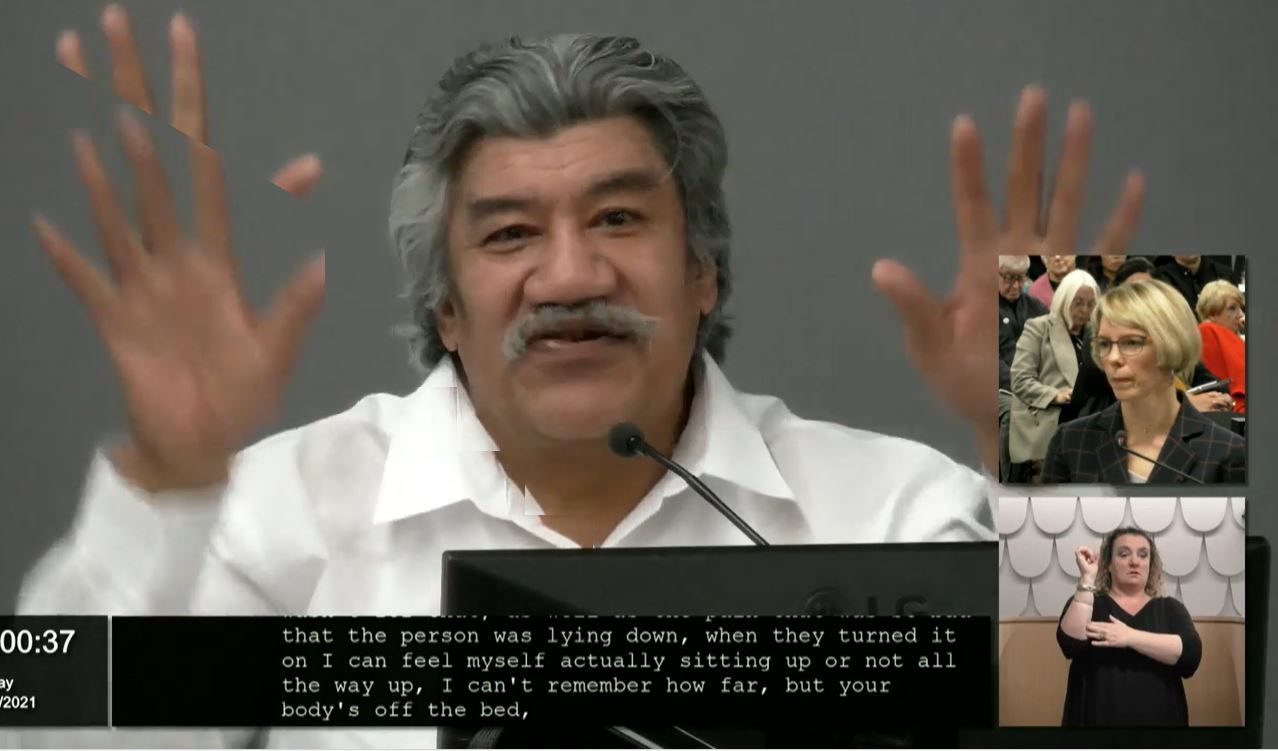

“The pain was so bad that when a person was lying down, when they turned it on, I could feel myself actually sitting up. Your body is off the bed ... you're straining to raise your arms but they’re holding you down. And they turn it off, that’s when you’re crying … without the mouthguard, a person would end up biting his tongue off because of the pain.”

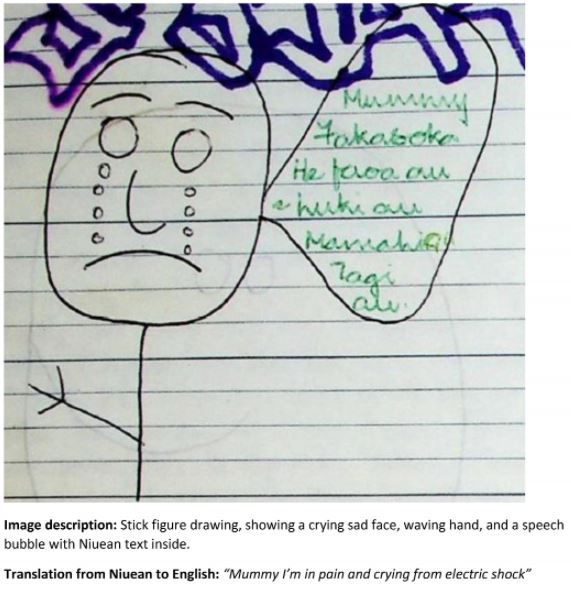

Hake tried to alert his family to the abuse he was experiencing by embedding messages in Niuean into drawings featuring smiling stick figures, which was his way of getting the truth past the staff. He died in September 2025, but his evidence and advocacy were instrumental in exposing the abuse at Lake Alice.

Tigilau Ness, a member of the Polynesian Panther Party and long-time social activist, supported Hake through the inquiry and remembers him fondly.

Hakeagapuletama 'Hake' Halo demonstrates how his hands would come up when he received electric shock treatment. Photo/Screenshot

“After all his trauma and experiences growing up, he was a gentle person, proud of his Niue heritage, and the most important message he wanted to get across was that what had happened to him should never happen again to any other children.”

Hake chose to receive an earlier payout before the new payment bands were introduced. Ness says it mattered for Hake to see some form of recognition before his death.

“There’s never enough money that could heal or fix…it’s people’s lives. [But] in Hake’s case, more should have been due, but if we hadn’t have got his money, he would have died without ever seeing any form of justice for what had happened to him.”

Year later, Hake Halo tried to recreate his coded drawings to his mother. Image/Supplied

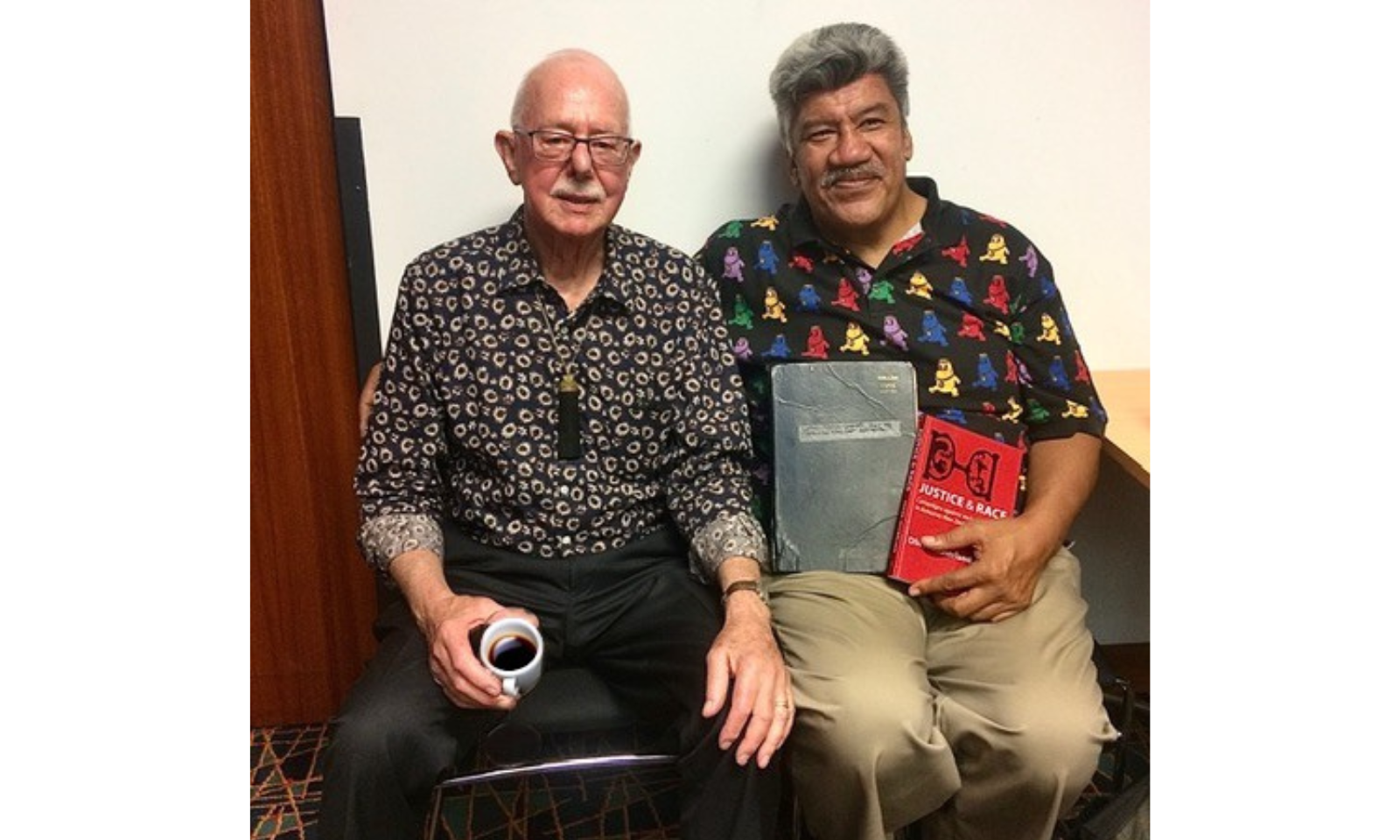

Dr Oliver Sutherland, a key member of the Auckland Committee on Racism and Discrimination, played a role in bringing Hake’s story to the public’s attention. He remembers meeting Hake as a teenager.

“He found a lot of comfort from the church that he belonged to. He was a lovely and thoughtful man, and he could have had perhaps a career in many directions, but what happened to him as a boy and as an adolescent really sort of militated against that.”

Listen to Tigilau Ness' full interview below.

Wider impact of abuse

The Abuse in Care Inquiry revealed decades of mistreatment in both state and faith-based care facilities between 1950 and 1999. It found that Pacific survivors were disproportionately harmed, denied cultural identity, prevented from speaking their languages, and subjected to overt racist abuse and harsher treatment than other children.

Ness says parents entrusted their children to state and church care, not knowing many would return changed or not at all.

“I remember my friends while I was at school; a lot of them disappeared. One minute they were with us, and were in the community, the next minute they were gone, and we heard, ‘Oh, they've been sent to a boy's home’.

“Now I understand what had happened to them; I could see the criminal involvement and the beginnings of how they ended up in prisons eventually.”

The Lake Alice Hospital has been abandoned since its closure in the late 1990s. Photo/Fergus Cunningham 2011

The Government formally apologised in 2024. In his speech, Prime Minister Christopher Luxon acknowledged the abuse documented by 2400 people who shared their experiences during the inquiry.

“Māori and Pacific children suffered racial discrimination and disconnection from their families, language and culture… places where you should have been safe and treated with respect, dignity and compassion. But instead, you were subjected to horrific abuse and neglect and in some cases, torture.”

In October, the Redress System for Abuse in Care Bill passed its first reading, which will require an independent review of financial payments for survivors who have committed serious sexual or violent offences, rather than automatically granting those payments.

Crowd at Due Drop Events Centre watch the apology Photo/Joseph Safiti

Ness says the redress must be accompanied by long-term, practical support, such as counselling, employment opportunities, and stable housing, to address the deep-rooted harm survivors continue to carry.

“The majority of gangs come from boys' homes... Of course, if they've committed crimes, yes, they're punishable for that, but the underlying thing is they've got to know and look at why they did those things.

“It's not that they just up and did it, it's because that's the only example they know, and they're hurt,” he says. “The majority of New Zealanders don’t really care or understand, not until their children get into trouble or trauma happens in their lives.”

Hake Halo (right) and Oliver Sutherland at his book launch in 2020. 'Hake is holding a copy of my book, and also his journal of his experiences at Lake Alice'. Photo/Supplied

A legacy of resistance

For long-time advocates, the fight to protect Māori and Pacific children from systemic racism has spanned generations. Sutherland’s advocacy, detailed in his autobiography, Justice and Race: Campaigns Against Racism and Abuse in Aotearoa New Zealand, continues this important work.

“We investigated government departments and bureaucracies and systems that were impacting Māori and Pacific children and their families.

“Although we were criticised for being rather too strident at the time, and the Minister of Justice or several of them didn't like being criticised, they did bring about some changes we had wanted. We argued for 10 years that children should not be remanded to prisons like Mount Eden… and a stop was put to that, and we achieved a duty solicitor scheme, which provided lawyers for children and adults going through the courts.”

This article has been corrected to state that the compensation rates were released by Erica Stanford in her role as Minister for the Government's Response to the Abuse in Care - Royal Commission of Inquiry, and not the Ministry of Social Development, as earlier reported.