An estimated 2.6 million people in the Pacific and Asia are stateless or lack a recognised nationality, the UNCHR says.

Photo/US committee for refugess and immigrants

Pacific urged to tackle homelessness as region hosts most stateless people, report reveals

More than half of the world's stateless population lives in Asia-Pacific, which the experts warn leaves children and adults without access to education, healthcare or legal rights.

‘Don’t suffer in silence’: Pacific families see spike in violent crime

The time when aunty, at age 11, threw a knife at grandpa over mum

NRL’s record millions but what does it mean for the Pacific Islands' other rugby code?

‘Don’t suffer in silence’: Pacific families see spike in violent crime

The time when aunty, at age 11, threw a knife at grandpa over mum

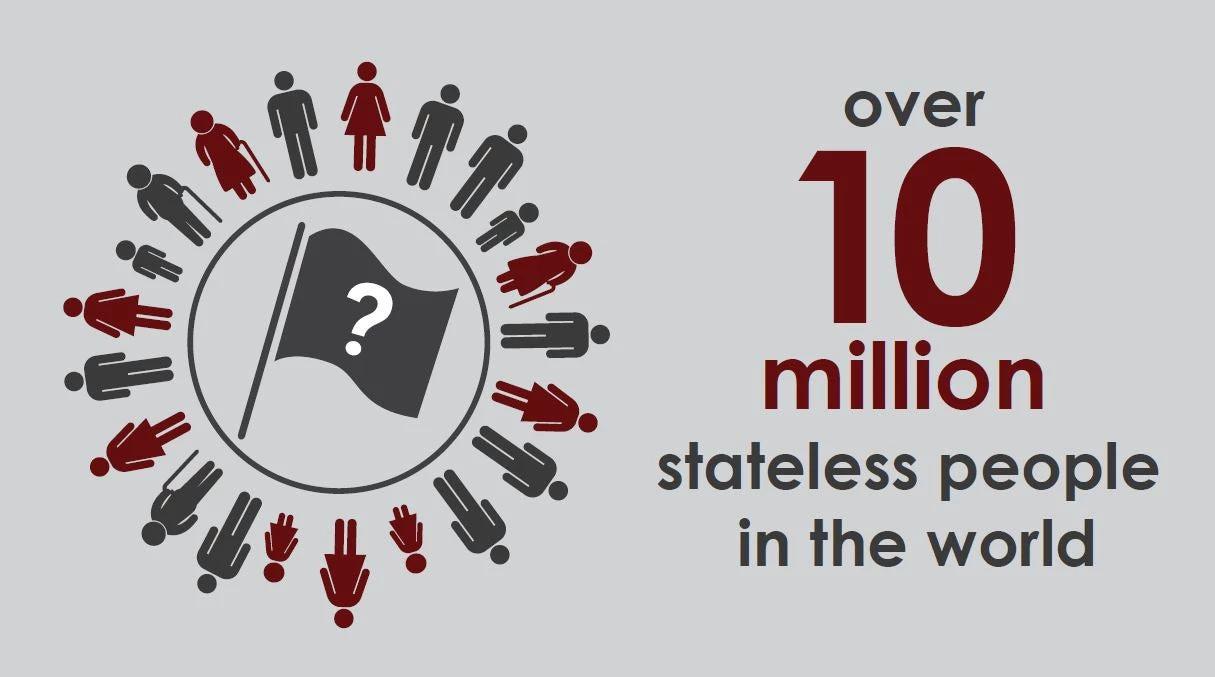

The Pacific is home to more than half of the world’s stateless population, leaving children and adults without access to education, healthcare, and legal rights, according to a new report by the United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR.

Communities in the Pacific are being urged to strengthen birth registration and nationality laws to ensure no one is left without citizenship.

An estimated 2.6 million people in the Pacific and Asia regions are stateless or lack a recognised nationality, the UNCHR says.

The Rohingya in Burma account for a large proportion, but statelessness also affects smaller Pacific populations, particularly in remote islands where births may go unrecorded.

“When a child is born without identity papers or a recognised nationality, they can be invisible to systems that provide education, healthcare, and a future,” a Pacific legal expert on nationality documentation highlights the challenges for families across the islands.

Statelessness occurs when a person is not considered a national by any country under its laws. Without nationality, people often cannot access vital services or assert legal identity.

Photo/World Bank

Infants may be denied vaccinations, children can be turned away from school, and adults may face barriers to employment, housing, and legal marriage.

The UNHCR says these outcomes harm both individuals and communities, undermining social cohesion and economic development.

In the Pacific, statelessness may be less visible, but risks are growing. Remote communities in Tuvalu, Kiribati, and parts of Papua New Guinea face gaps in civil registration, leaving children without legal documentation.

“Without recognised legal status, people are left on the margins unable to fully belong or claim their rights,” a regional human rights advocate, speaking on the need for robust documentation systems in the Pacific, says.

Climate change adds another layer of risk. Rising sea levels and severe weather are already threatening villages and entire islands in low-lying nations, forcing relocation.

Displaced families may struggle to maintain nationality, especially if births occur during migration or in temporary settlements abroad.

Loss of government offices, land records, and civil registries in disasters can further prevent residents from proving citizenship.

The UNHCR warns that without preemptive legal protections, climate displacement could create a new wave of “climate statelessness” in the Pacific.

Pacific governments are beginning to respond. New Zealand, for example, ensures children born on its territory can acquire citizenship, reducing the risk of statelessness.

Tens of thousands of people in New Zealand still live without stable housing, including in emergency shelters or on the streets. Photo/thequo.com.au

But tens of thousands of people in New Zealand still live without stable housing, including in emergency shelters or on the streets.

Advocates warn this shows how housing insecurity and legal identity challenges can intersect.

Other island nations are improving birth registration, though gaps remain in remote areas.

Experts say stronger legal frameworks, mobile civil registration outreach, and better disaster-preparedness measures could prevent future statelessness.

Indrika Ratwatte, UNHCR’s regional director for Asia and the Pacific, emphasised that statelessness is solvable.

“Ending statelessness restores dignity, unlocks opportunities, and allows people to fully belong in the communities they call home,” she says.

Listen to Will's Word on Pacific Mornings below.

Hundreds of asylum seekers remain in offshore detention centres in Nauru and Papua New Guinea, many living in limbo for years with limited rights, documentation, or certainty about their future.

Some face more risks of statelessness - children born in detention or those with unclear legal status highlight the displacement and nationality challenges in the region.

Pacific civil society and legal experts are calling on governments to act now to safeguard children and families at risk from both administrative gaps and climate-related displacement.

They say that by ensuring every child is registered at birth and nationality laws are inclusive, Pacific nations can protect vulnerable populations and prevent lifelong exclusion.

The UNHCR report serves as a stark reminder: statelessness is not only a legal problem but a human one.

In the Pacific, addressing it is increasingly linked to responding to climate change and preserving the futures of communities facing environmental and administrative challenges.