Deep sea mining extracts minerals used in technologies like electric vehicle batteries, solar panels, and smartphones.

Photo/SPREP

Deep sea mining: What it is and why the Pacific is at the centre of it

As demand for green tech metals grows, island nations are central to a global scramble that may reshape international law and marine ecosystems.

Artist brings Pacific weaving to New Zealand’s deep south

New Attorney-General as Sāmoa reviews national legal system

Will’s Word: The new statewide political poll points to a cliffhanger

Artist brings Pacific weaving to New Zealand’s deep south

New Attorney-General as Sāmoa reviews national legal system

Deep sea mining has grown to become both a contentious and polarising practice in the Pacific. It is viewed as either a pathway to economic prosperity or a source of environmental devastation.

Deep sea mining extracts minerals like cobalt, nickel, manganese, and rare earth elements from the ocean floor, often several kilometres beneath the surface. These metals are used in various technologies such as electric vehicle batteries, solar panels, and smartphones.

The demand for these minerals is driven by global efforts to move towards green energy, which has been a driving point that deep sea mining supporters have advocated as a major advantage.

The Pacific region includes the highly-valued Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), which is a mineral-rich area between Hawaii and Mexico. In 1994, the United Nations established the International Seabed Authority (ISA) to oversee mining activities in international waters such as the CCZ.

Countries seeking to mine in the CZZ must apply for an exploration contract through the ISA. If approved, they are given a portion of the deep sea, but must reserve an equivalent portion for a developing country.

Other countries or companies can also access this reserved area by partnering with developing nations. The Canadian-based The Metals Company (TMC) has sponsored projects through Nauru, Tonga, and Kiribati. So far, the ISA has issued 31 exploration licences, 17 of which are located in the CCZ.

Bypassing the ISA

Nauru recently signed a contract with TMC that aligns it with US deep sea mining legislation, effectively bypassing the ISA. Nauru will pay TMC up to US$515 million (NZ$862m) upfront, with the option to buy shares in its own company.

Tonga has drawn a similar response from legal expert Lori Osmundsen, who attended a recent parliamentary talanoa on deep sea mining in the island nation. Osmundsen praised Tonga for hosting the open discussion.

But she warned that Tonga’s long-term mining contract with Tonga Offshore Mining Limited, a subsidiary of the US-based Metals Company, could impact international law. Environmental concerns surrounding this practice also loom large, as some Pacific nations struggle with the ethical versus economic considerations.

Environment and economy: The Pacific wrestle

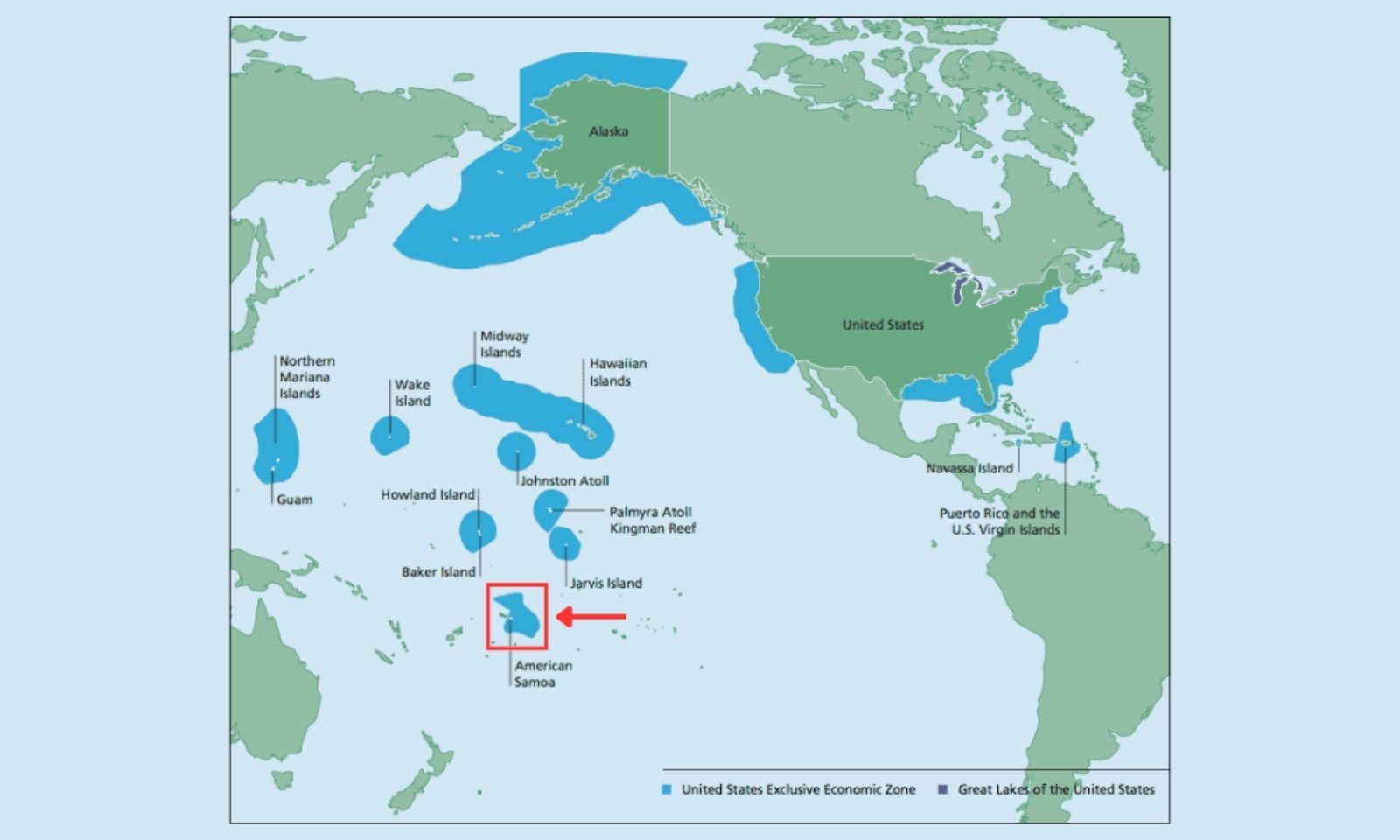

One concern is how deep sea mining disrupts ocean life through noise and light pollution, as well as by stirring up sediment plumes. In April, the US-based Impossible Metals company requested a commercial auction from the US government to mine polymetallic nodules near American Sāmoa.

Since the site lies within US territorial waters, it does not require ISA approval. The company aims to use autonomous underwater vehicles to selectively harvest nodules while minimising harm to marine life.

The company has also committed to local investment, agreeing to pay American Sāmoa one per cent of its profit share while involving the potential for US Federal government investment in critical infrastructure, job training, and capacity-building opportunities.

In April, the US-based Impossible Metals company requested a commercial auction from the US government to mine polymetallic nodules near American Sāmoa. Photo/Impossible Metals

Meanwhile, Cook Island residents are concerned about deep sea mining impact on fish stocks and ocean health, which are vital for the livelihoods of outer island communities. In an RNZ report, Opposition Leader Tina Browne criticised her government’s “aggressive promotion of mining” despite scientific evidence being inconclusive.

As the Pacific navigates the pros and cons of deep sea mining, it finds itself at the centre of geopolitical tensions among superpowers striving to improve the ocean.

Whichever way it unfolds, it is clear that the Pacific’s most contentious issues are complex and multifaceted.