Dr Monica Tromp leads a team of researchers analysing ancient DNA and other evidence from early Pacific cultures.

Photo/Supplied/Amuraworld.com

Ancient DNA study reveals unique history of Pacific migration

The ground-breaking research challenges the idea of a single ancestral culture and sheds light on the social dynamics of the region’s ancient people.

From development squad to World Series: Teenager earns Black Ferns Sevens contract

Pacific champions eye place on football’s biggest Oceania stage

From development squad to World Series: Teenager earns Black Ferns Sevens contract

A recent analysis of ancient genomes is transforming our understanding of the origins and migration paths of early Pacific people.

The ground-breaking international study examined ancient DNA from Papua New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago, a chain of islands off its eastern coast.

The findings suggest that early Pacific cultures were much more diverse and complex than previously believed.

Dr Monica Tromp, a co-author and researcher at Otago University’s Southern Pacific Archaeological Research (SPAR), says the study challenges the idea of a single ancestral culture.

“Rather than being one unified group, these ancient communities represented a rich tapestry of different cultures and peoples,” she tells William Terite on Pacific Mornings.

“There were groups with distinct languages and customs living alongside each other several thousand years ago, but many were so different they didn’t really want to hang out with each other.”

The research combines ancient DNA (aDNA), archaeological evidence, dietary data, and linguistic analysis to trace the movements and interactions of early Pacific cultures.

Tromp says the team found major cultural differences among groups in southern Papua New Guinea.

“One group showed signs of skull modification. They were binding their skulls, which would have created a very distinct look and strong cultural identity. Meanwhile, a nearby group practised cave burials. These contrasting traditions were right next to each other.”

Watch the full interview with Dr Monica Tromp below.

Close, but separate

Dr Rebecca Kinaston, research co-lead researcher and director of archeology consultancy BioArch South, says that despite living side by side for centuries, the groups did not intermarry for long.

The genetic findings also help settle a long-standing debate about the order of settlement in remote Oceania.

“They were there at the same time, but they were so distinct they didn’t really interact … which is quite unusual for human encounters,” Kinaston says.

“The delay in intermarriage and the presence of people with Papuan ancestry suggest the first settlers likely arrived unmixed and were later joined by Papuan groups.

“Surprisingly, their ancestries started diverging 650 years ago, despite the absence of geographical borders.”

Excavation site on Watom Island, PNG, in 2009. Photo/Rebecca Kinaston

New clues from old pottery

Tromp says genetic and pottery evidence reveals that the Lapita people, who are considered ancestors of many Pacific nations, kept their distance from the earlier Papuan culture that arrived about 50,000 years earlier.

She says the Lapita people were some of the world’s greatest explorers. The study identified individuals with Papuan ancestry on Watom Island, where Lapita-style pottery was first discovered in 1909.

“They [Lapita] were sailing into the endless blue horizon centuries before Europeans ever dared to leave their coastlines,” Tromp says.

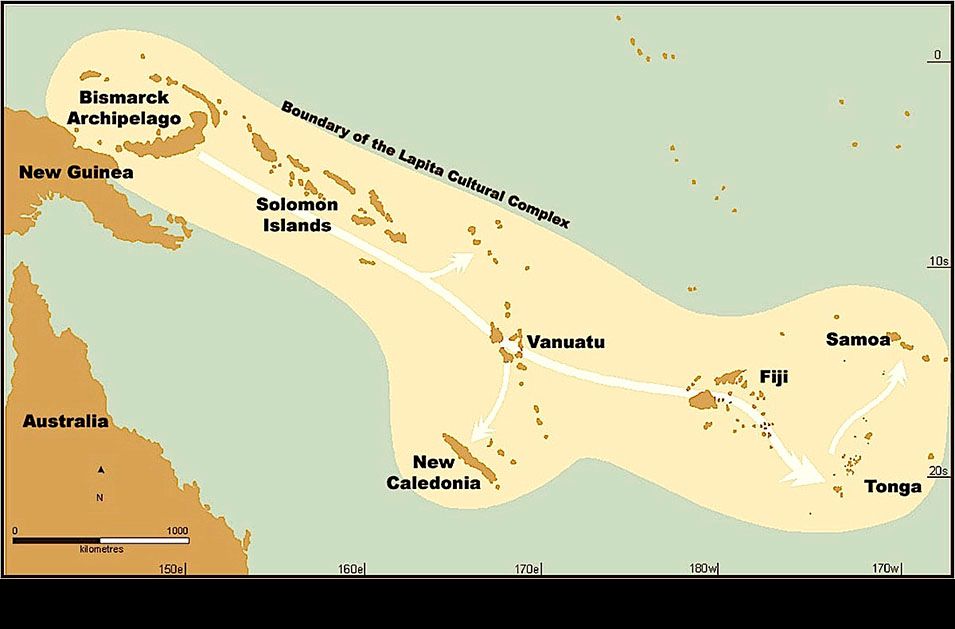

“You don’t see much of the pottery and cultural items until you get to that area. They seem to have stayed there for a while before spreading further, to Vanuatu, Tonga, and Sāmoa, and eventually across the wider Pacific.”

Migration pathway of the Lapita population. Image/Matangi Tonga

In Vanuatu, Tromp reported evidence of a unique cultural crossover.

The findings enrich oral traditions that have passed down through generations, but Tromp stresses that they should not be used to challenge modern cultural identities.

“A few thousand years later, people with Papuan ancestry came in and completely replaced the genetic makeup of the population, but the Austronesian language remained. The genetics changed, but the language of the Lapita people survived,” she says.

“We don’t try to link these ancient populations to specific groups today, because they’re likely ancestors of all Pacific peoples. Trying to pin them down to one modern community isn’t helpful.”

Research co-author Dr Rebecca Kinaston with local potter in the Reber-Rakival village, Watom Island, 2009. Photo/Kasey Robb

Ethics and collaboration

The study, co-led by the Max Planck Institute in Germany, involved more than a decade of collaboration among experts in archaeology, genetics, chemistry, linguistics, and cultural history.

Tromp says technological advances have recently made such genetic analyses possible, particularly in tropical climates where DNA typically degrades quickly.

“This project has taken well over ten years - just to gather the data and get the right people involved,” she says. “It’s exciting to finally share it and see what we can explore next.

“The DNA analysis that made these discoveries possible would’ve been impossible just a decade ago.”

Professor Glenn Summerhayes overseas surveying in Bilbil, Madang Province PNG. Photo/Supplied

The project also reflects a shift in archaeological practice, emphasising ethical research.

Otago University is now focused on growing the next generation of Pacific researchers to carry this work forward.

“We work closely with the communities connected to these archaeological sites and urupā [burial grounds]. They’re given access to the data before it’s published,” Tromp says.

“There’s a lot more discussion between researchers and local communities these days.”

“We have a really strong Pacific student cohort here,” Tromp says. “We’re committed to training Pacific archaeologists so they can go back and work in their communities.”