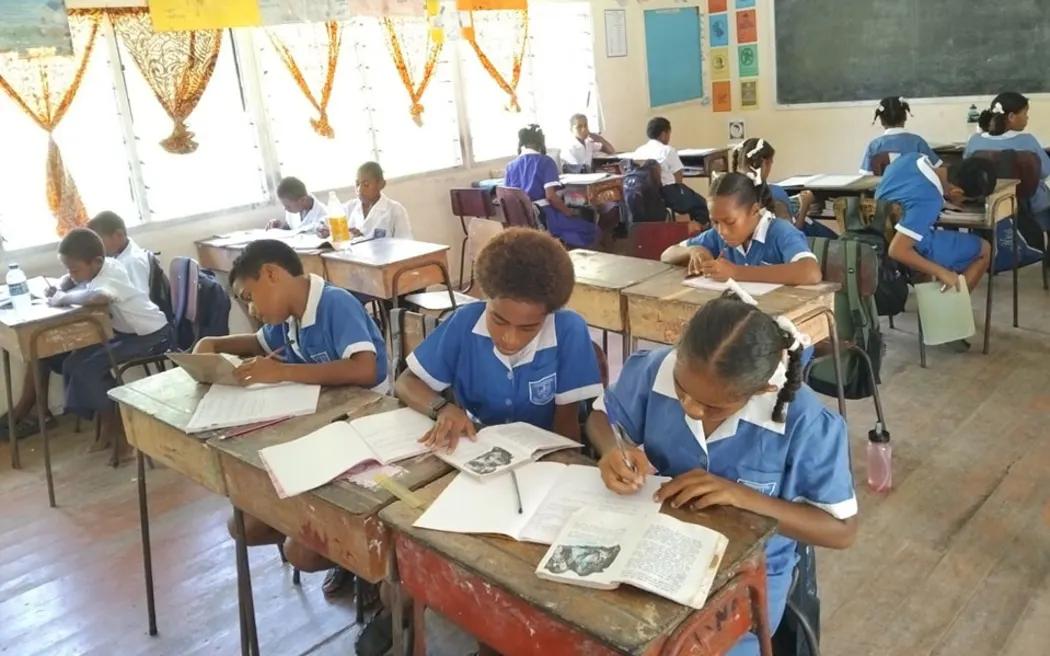

Overcrowded classrooms in Fiji are placing significant stress on teachers, impacting their ability to manage student behaviour effectively.

Photo/Ministry of Education

Beyond the Belt: Fiji schools struggle with teacher stress and behavioural crisis

Advocates are urging systemic reforms, including counselling and support services, to tackle the root causes rather than resorting to punishment.

‘Shot put queen’ Dame Valerie Adams leads Pacific pride at NZ's Halberg Awards 2026

Pacific digital-finance push continues despite global crypto volatility

Fiji fast-tracks needle programme as new study shows HIV cases surging at record pace

‘Shot put queen’ Dame Valerie Adams leads Pacific pride at NZ's Halberg Awards 2026

Pacific digital-finance push continues despite global crypto volatility

Content warning: This article discusses violence against children.

Fiji is witnessing a heated debate over the reintroduction of corporal punishment in schools, but experts say the discussion is only scratching the surface.

While headlines have focused on whether teachers should be allowed to use physical discipline, a deeper issue is emerging: teachers are overburdened, student behavioural challenges are escalating, and schools lack adequate support systems to manage both.

The debate reignited after the Fijian Teachers Association (FTA) called for the legal return of corporal punishment, citing increasing classroom disruptions and declining student respect for authority.

Paula Manumanunitoga, the FTA General Secretary, argued that teachers, particularly in rural boarding schools, are stretched beyond their capacity.

“Teachers are facing unprecedented stress, and the current disciplinary framework does not equip us to manage complex behavioural issues,” Manumanunitoga says.

He also raised the question of teachers’ classification as civil servants, suggesting that their work in schools, often in remote areas and with residential responsibilities, is not comparable to traditional office-based roles.

While the FTA framed corporal punishment as a practical solution to maintain order, child protection advocates, legal experts, and international organisations have uniformly condemned the proposal.

Save the Children Fiji called the suggestion “illegal, unconstitutional, and unsafe,” emphasising that Fijian law prohibits physical punishment in schools and that any violation of this law breaches both national child protection statutes and international commitments.

Disruptive student behaviour is on the rise in Fiji's schools, prompting discussions about discipline methods. Photo/Facebook

“The return of corporal punishment is not just a policy issue. It’s a child safety issue,” Shairana Ali, chief executive of Save the Children Fiji, says.

“Advocating for belts and physical discipline exposes children to harm and undermines the very purpose of education: to foster learning and development in a safe environment.”

Adding a new dimension to the debate, education authorities and child development specialists argue that the focus should shift from punishment to systemic support.

Michael Copland, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) Pacific’s Chief of Child Protection, stressed that the conversation should centre on creating safe, structured learning environments and equipping teachers with the tools to manage student behaviour without resorting to violence.

“This isn’t simply about punishment,” Copland says. “It’s about why students are misbehaving, how schools are responding, and whether teachers are getting the professional support they need to succeed.”

Several participants in a recent talanoa (dialogue) organised by the Ministry of Women, Children and Social Protection echoed these concerns. Abhay Chand, founder of the Influence Global Network, highlighted the potential of school-based counsellors and behavioural specialists to address the root causes of classroom disruptions.

“Counsellors can help students navigate emotional and social challenges, giving teachers the bandwidth to focus on teaching rather than policing behaviour,” Chand says.

Metuisela Gauna, head of Planning, Policy, and Research at the Ministry of Education, says some teachers have already received training in counselling techniques, and that the ministry plans to gradually expand these roles across schools.

The approach represents a shift from reactive punishment to proactive support, signalling a potential long-term solution to classroom management issues that are driving calls for corporal punishment.

Parents have also been drawn into the discussion. Minister for Education, Aseri Radrodro, reminded families that child discipline begins at home. “Teachers teach, they are not part of the disciplinary forces,” Radrodro says, urging parents to take primary responsibility for their children’s behaviour. “School is for learning; home is for guidance.”

Observers say that framing the debate solely around corporal punishment risks missing the bigger picture.

Fiona Reddy, a sociologist specialising in education in the Pacific, argues that the discussion highlights structural problems within the education system.

“Teachers are under stress, classrooms are crowded, and support services are minimal,” Reddy says. “Calls for corporal punishment are a symptom of systemic failure, not a genuine solution.

Investing in teacher training and support is crucial for addressing classroom management challenges in Fiji. Photo/Ministry of Education, Fiji

"Without addressing teacher workload, student counselling, and classroom resources, any discussion of discipline is incomplete.”

The debate also exposes a generational and cultural tension. Older practices, including corporal punishment, remain embedded in some traditional communities, while modern child protection laws and international conventions increasingly shape expectations of safe schooling.

Experts warn that failing to navigate these tensions carefully could undermine both student well-being and public trust in the education system.

As the government and educators continue to discuss policy options, international observers and local advocacy groups are pressing for solutions that prioritise student safety, teacher support, and positive behavioural interventions.

The outcome of this debate may determine not only whether corporal punishment ever returns to Fijian schools, but also whether systemic reforms are implemented to support teachers and students alike.

Child advocates say collaboration between parents, teachers, and the community is essential for creating a positive learning environment in Fiji's schools. Photo/RNZI/Sally Round

For now, Fiji’s classrooms are at a crossroads. The conversation has moved beyond the narrow question of whether a belt or a cane should be used.

It is now about reimagining the educational environment to address behavioural challenges, protect children, and empower teachers to teach effectively without fear, stress, or violence.

The latest discussions highlight that the most urgent need is not punishment, but professional support for teachers and structured behavioural guidance for students - an angle that may finally move the debate beyond the headlines into concrete policy solutions.