Travellers at Nadi International Airport in Fiji where new US visa restrictions have disrupted travel and family visits across the Pacific.

Photo/The Fiji Times/Baljeet Singh

US visa crackdown leaves Pacific families in limbo, experts warn

The travel restrictions affecting island nations are raising fears about family separation, migration pathways, and long-standing regional ties.

Cook Islands Prime Minister to visit New Zealand amid lingering diplomatic rift - report

French Polynesia urges Pacific to unite amid rising global tensions

Tennis with purpose: Taleia Tuatao uses sport to serve others

Cook Islands Prime Minister to visit New Zealand amid lingering diplomatic rift - report

French Polynesia urges Pacific to unite amid rising global tensions

Pacific political analyst Tess Newton-Cain says new United States visa bonds and travel restrictions risk reshaping how Pacific people move, migrate, and maintain family ties.

She warns the policies could have long-term consequences across the region.

In an interview with Pacific Mornings host William Terite, Newton-Cain says the measures are already causing concern for Pacific communities. “Obviously, it’s going to cause significant concerns for particular Pacific Islanders that come from these countries.”

Pacific Islanders and diaspora communities are facing mounting frustration and uncertainty after the US introduced sweeping changes to its visa system, including a pause on immigrant visa processing for citizens from 75 countries and the introduction of costly visa bonds.

Under the new measures, which began taking effect at the start of 2026, nationals from affected countries are unable to obtain new immigrant visas while the suspension remains in place, a change that could endure indefinitely.

In the Pacific, Tonga’s travel restrictions officially began on 1 January this year, with visa issuance for short-term visits, tourism and business purposes also suspended for Tongans.

Fua’amotu International Airport, Tonga’s main gateway for international travel, now under the spotlight as US visa bond rules place new financial and logistical pressures on Pacific travellers. Photo/wikimedia/lirneasia

The clampdown has stirred anger and anxiety among both locals and the American Tongan diaspora, many of whom have close family, church and cultural ties spanning the Pacific and the US.

Newton-Cain says measures such as visa bonds affect Pacific families wanting to travel.

“These measures affect not so much the people that live there, but the people that want to visit - for family events, weddings, funerals, just holidays in general,” she says. “There’s obviously a significant financial burden as well with the introduction of bonds.”

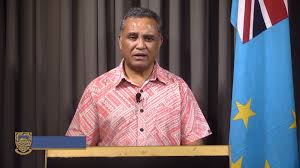

Fiji Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka says his country faces US visa policy changes and “we brought it on ourselves” because of high rates of unlawful immigration to the United States. Photo/Fiji government

Fiji has also been directly affected. Under the new visa bond scheme, Fijian passport holders applying for US visitor visas may be required to post bonds ranging from US$5000 (NZ$8656) to US$15,000 (NZ$25,968) before approval, a cost many say will put travel out of reach.

Fiji's Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka has addressed the issue publicly, telling local media his country “brought it on ourselves” because of high rates of unlawful immigration to the United States.

“We rank very highly. They are illegal immigrants. They are there without authority and must be dealt with according to the law of the United States,” he told the Fiji Sun.

Rabuka’s comments have drawn criticism from Fijians at home and abroad, who argue the new rules unfairly punish families and law-abiding travellers.

Concern is also growing in Tuvalu after the island nation was flagged in earlier US assessments. The Tuvalu government has described its inclusion as a “systemic error”, warning that the impact would be severe for citizens seeking mobility amid rising sea levels.

Tuvalu’s High Commissioner to New Zealand, Tapugao Falefou, says his government is seeking written assurances that Tuvaluans will not be unfairly barred.

Tuvalu High Commissioner to New Zealand, Tapugao Falefou, says his government is seeking assurances from the US that their citizens will not be fairly barred after visa restrictions were announced. Photo/Facebook

Newton-Cain says restricting migration pathways for climate-vulnerable nations runs counter to global discussions about climate displacement and responsibility.

According to US State Department guidance, the visa pause targets those considered likely to become a “public charge”, citing overstays and welfare use as factors.

Newton-Cain says the lack of transparency around how Pacific countries were assessed has added to mistrust, with governments left unclear about what steps could lead to restrictions being lifted.

As the policy takes effect this week, families across the Pacific are racing to finalise travel plans while diplomatic discussions continue.

For many Pacific Islanders, uncertainty and frustration now loom as they wait for answers from Washington.

This article has been updated to correct quotes previously misattributed to Newton-Cain. We apologise for the error.

Listen to Tess Newton-Cain's full interview below.