Pacific Islands Forum Secretary General Baron Waqa, left, and Asian Development Bank President Masato Kanda sign a partnership agreement to strengthen regional cooperation and integration. Photo/Pacific Islands Forum

Photo/PIF

Asian Development Bank expands Pacific footprint with Suva hub and new PIF agreement

ADB is deepening its Pacific engagement having already invested billions of dollars across the region. But who is the bank, how does it work, and what exactly does it do for island nations?

UK royal arrest sends shockwaves as Jeffrey Epstein files reference Pacific islands - reports

Second Apology: Fijian artist’s bold new film demands more for Pacific communities

UK royal arrest sends shockwaves as Jeffrey Epstein files reference Pacific islands - reports

Second Apology: Fijian artist’s bold new film demands more for Pacific communities

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is growing its presence across the Pacific by expanding its office in Suva, and formalising a new partnership agreement with the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF).

ADB President Masato Kanda and Forum Secretary General Baron Waqa signed what they described as a ‘landmark agreement’ in Suva on Friday, to accelerate regional cooperation on economic development.

On the same day, Kanda joined Fiji Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka to open ADB’s expanded office in Suva. The office will serve as a regional hub for seven countries: the Cook Islands, Fiji, Kiribati, Niue, Sāmoa, Tonga, and Tuvalu.

The new PIF agreement aims to align ADB financing and technical expertise more closely with regional priorities agreed by PIF leaders, coordinating support for climate finance, fiscal resilience and disaster risk funding mechanisms at a regional level.

Officials say the goal is to improve efficiency and ensure funding matches long-term Pacific strategies, including work on the blue economy.

But what does the ADB do in the Pacific, how is it funded, and why does its role matter to island countries?

President of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) Masato Kanda, left, and Fiji Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka at the official opening of the bank’s Pacific Subregional Office in Suva. Photo/Fiji Government

Where the money goes

The ADB was established in 1966, when many Asian and Pacific nations were newly independent and seeking long-term development financing. Based in Manila, the bank was created to reduce poverty and support economic growth through infrastructure investment and policy support across the Asia-Pacific region.

In the early 1970s, the ADB began expanding its operations into Pacific island countries. Fiji joined in 1970, followed by other Pacific members over subsequent decades, including Papua New Guinea, Sāmoa, Tonga, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu.

The ADB manages more than US$250 billion (NZ$418 billion) in total assets and provides about US$30 to US$40 billion (NZ$50 to NZ$67 billion) each year in loans, grants and other forms of financing across Asia and the Pacific.

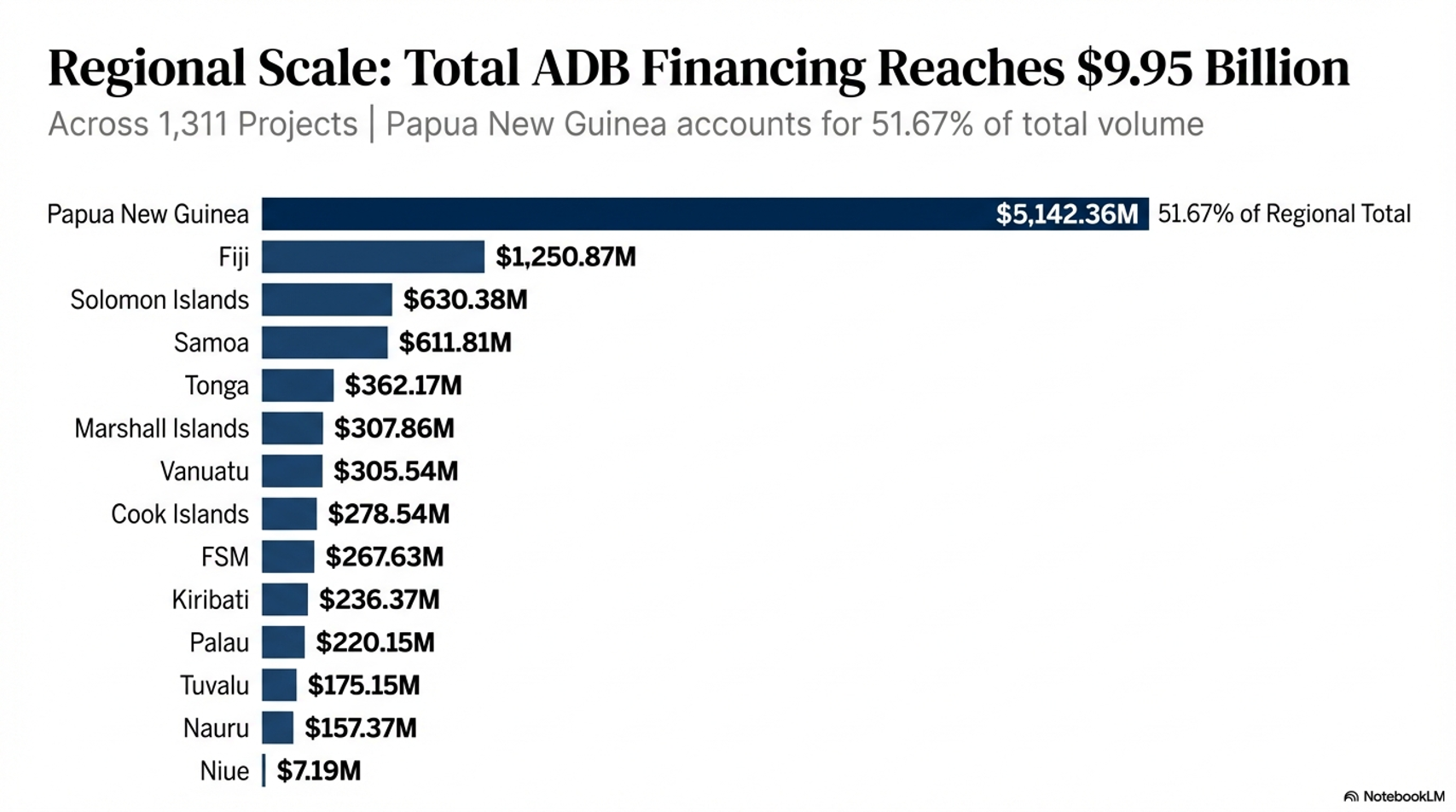

This chart was created by PMN News based on the latest data set available from ADB using AI tool NotebookLM.

Since 1972, the ADB has committed about US$10 billion (NZ$16.7 billion) in total financing across the Pacific, including direct loans and funds managed alongside international partners, making it one of the region’s largest multilateral lenders.

Papua New Guinea remains the bank's biggest Pacific client, receiving roughly US$5.1 billion (NZ$8.5 billion), about half of the regional total. Fiji is the second largest, with about US$1.3 billion (NZ$2.2 billion) in total commitments, accounting for approximately 12.6 per cent of the bank's Pacific portfolio.

In its early years in the Pacific, ADB funding focused heavily on core infrastructure such as roads, ports, power generation and telecommunications. As Pacific economies evolved, their role broadened to include public sector reform, private sector development, and more recently, climate adaptation and disaster resilience.

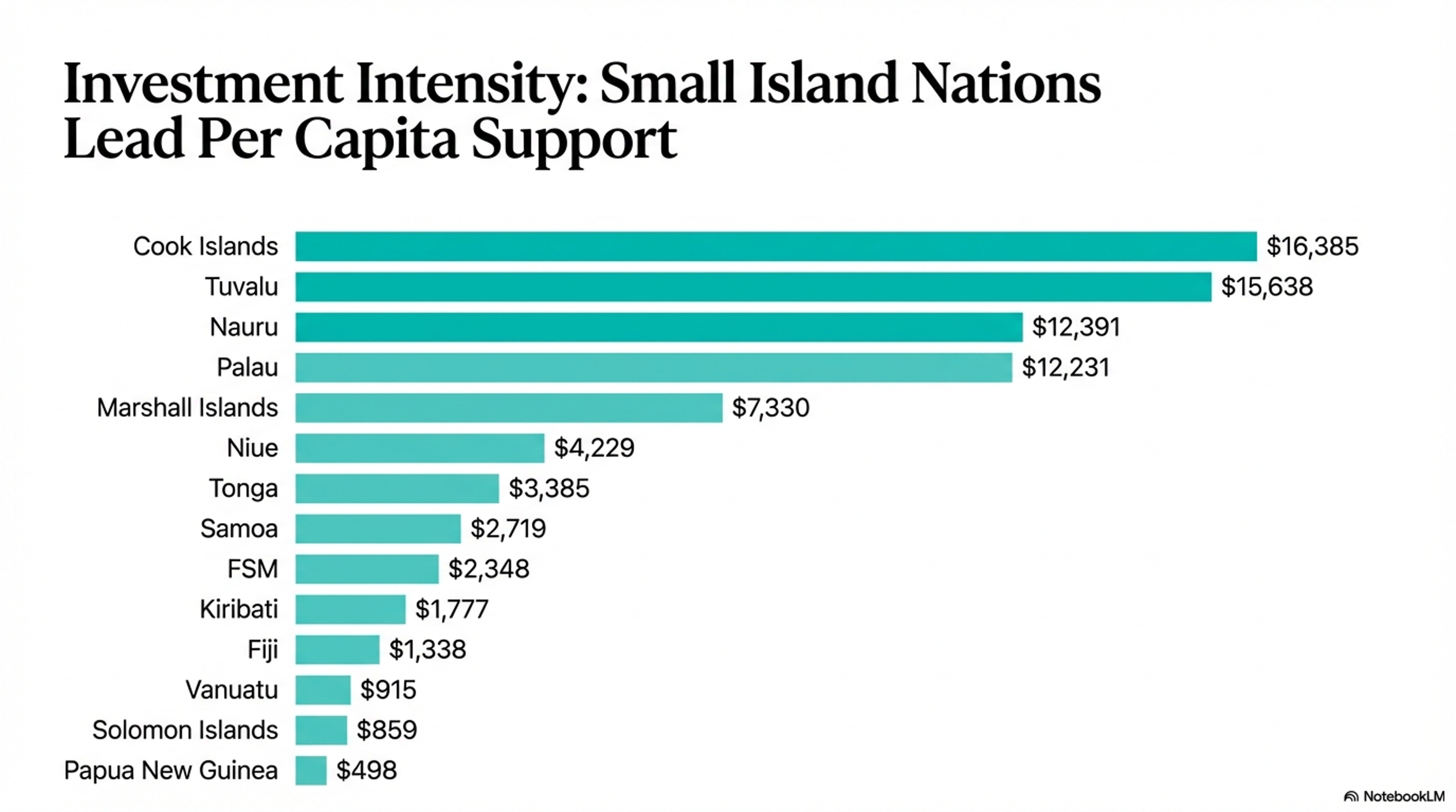

This chart was created by PMN News based on the latest data set available from ADB and 2024 population figures using AI tool NotebookLM.

Following major natural disasters, including cyclones in Tonga, Vanuatu and Fiji, ADB has played a key role in post-disaster reconstruction financing, often providing rapid-response funding alongside grant support. Over the past two decades, climate change mitigation and resilience have become central pillars of its Pacific strategy.

Today, the ADB works with 14 Pacific developing member countries. While the scale of its lending in the Pacific is modest compared with its operations in larger Asian economies, its relative importance is considered significant, given the limited domestic revenue and borrowing capacity of many island states.

How ADB is funded

The ADB raises most of its lending funds by issuing bonds on global financial markets, supported by shareholder capital that underpins its credit rating.

It then lends that money to developing member countries, often on concessional terms with low interest rates and long repayment periods. Lower-income Pacific countries receive a higher proportion of grants, which do not need to be repaid, through the Asian Development Fund and climate-focused trust funds supported by donor governments.

For many Pacific island states with small domestic revenue bases, multilateral development financing is central to funding major infrastructure.

In addition to loans and grants, ADB provides technical assistance. This can include support for project design, procurement processes, fiscal management reforms and policy advice in sectors such as energy and transport.

The bank often co-finances projects with institutions such as the World Bank to assemble larger funding packages.

Who funds the bank?

Donor countries including Japan, Australia and New Zealand contribute capital and funding to ADB’s concessional windows. Their support helps determine how much grant and soft-loan financing is available to Pacific countries, particularly for climate resilience and public sector reform.

Approved in 2014, with US$5 million in grant funding from ADB and an additional US$750,000 from the Government of Australia, the Sāmoa Agribusiness Support (SABS) Project is helping commercial agribusinesses recover from the pandemic and grow sustainably, including the family-run business of Jennifer and Mary Howman, who produce Sāmoa’s Favourite Chips using local breadfruit, banana and taro, with improved access to finance and markets. Photo/ADB

Japan is the single largest ADB shareholder, holding about 15.6 per cent of total shares, the same as the United States. Japan is also the largest contributor to the Asian Development Fund (ADF), which provides grants and highly concessional loans to lower-income member countries, including many Pacific island states.

Australia ranks among ADB’s top 10 shareholders, with around 5.8 per cent of shares. It is also one of the largest contributors to the ADFs. New Zealand is a smaller shareholder, holding just under one per cent of ADB shares, but it is considered a significant Pacific-focused donor.

Challenges and transparency

However, the ADB’s role has not been without scrutiny.

In June 2025, Australian officials raised concerns about infrastructure projects in Papua New Guinea funded by the ADB that were publicly branded by Chinese state-owned contractors, creating confusion over who financed the works. The ADB is reviewing its branding and communication practices.

A project backed by the Asian Development Bank, Australia and the PNG government has improved rural health care across eight provinces, building 38 new facilities, strengthening frontline services and launching a digital system covering 840 health clinics. Photo/ADB

Late last year, the ADB faced further questioning after reports that contracts had been awarded to Chinese firms alleged to have links to forced labour practices in Xinjiang, prompting the bank to strengthen its safeguard and due diligence framework.

As the ADB deepens its regional partnership with the Pacific Islands Forum and expands its Suva presence, its influence in shaping infrastructure and development financing across the Pacific is likely to grow.

The question for governments and communities will be how effectively that funding translates into resilient infrastructure, sustainable growth and transparent delivery.