A descendants of Ro Veidovi Logavatu, Ro Alivereti Doviverata, carries his remains during a traditional ceremony in Lomanikoro Village, Rewa, as the chief was finally laid to rest on ancestral land. At left is Ro Teimumu Kepa, the current Marama Bale na Roko Tui Dreketi.

Photo/The Fiji Times/Jonacani Lalakobau

After 186 years, a Fijian chief comes home

Ro Veidovi Logavatu, who was taken overseas by American naval officers, has been laid to rest in Fiji.

Vanuatu cabinet convenes emergency meeting over escalating Ambae volcano

New generation of Pacific midwives strengthens Wellington maternity care

From the cradle to the grave: Cook Islands modernises civil registration process

Vanuatu cabinet convenes emergency meeting over escalating Ambae volcano

New generation of Pacific midwives strengthens Wellington maternity care

After nearly two centuries, the remains of Fijian chief Ro Veidovi Logavatu have finally been laid to rest in his homeland, in a ceremony that for many in Fiji marks both closure and a quiet reclaiming of history.

What remains of the chief - his skull, long held at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC - was flown to Nausori Airport on the weekend and carried with ceremony to Lomanikoro Village in Rewa, about 10 miles from the capital Suva, before being laid to rest in the chiefly burial grounds of Narusa.

For the Rewa Province and the wider iTaukei (indigenous) community, it was an emotional moment.

“Today [Saturday] was a complete cycle for Ro Veidovi as he was finally laid to rest with his family at our chiefly burial grounds,” Ro Teimumu Kepa, the current Roko Tui Dreketi and one of Fiji’s high chiefs, told The Fiji Times. “186 years later, he can now rest peacefully.”

Accompanying the remains were traditional rites and a short church service, blending spiritual and cultural meaning into a long-awaited homecoming.

Fiji’s Ambassador to the United States, Ratu Ilisoni Vuidreketi, was also part of the delegation that brought Veidovi home.

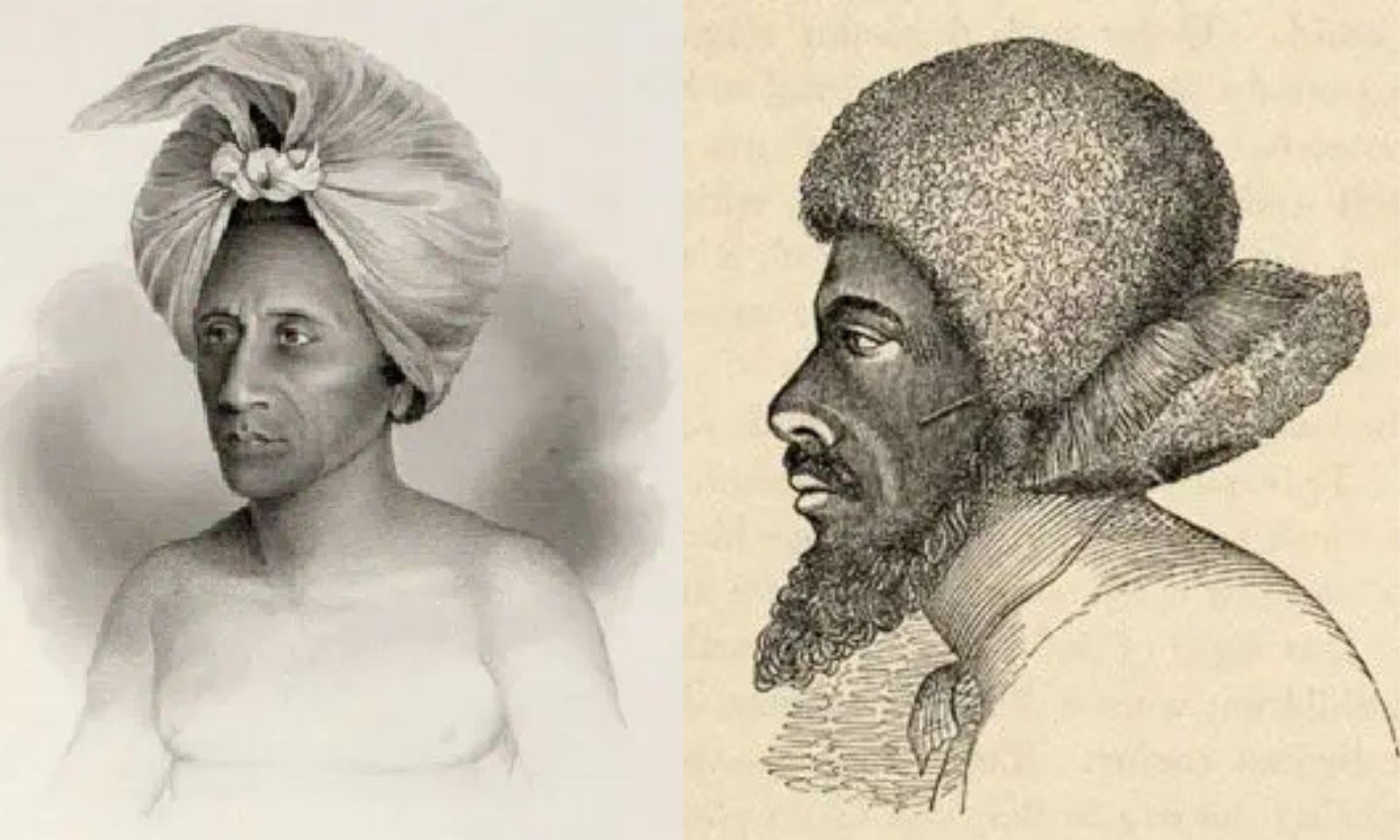

Ro Veidovi Logavatu, a chief of Rewa, who was taken from Fiji in 1840 and died in the United States two years later. His remains were returned to Fiji nearly 186 years after his exile. Photo/American Historical Society/Alfred T Agatei

For diasporic and local Pacific readers alike, the return speaks to the importance of place, belonging and the ties between land and identity.

In many Pacific cultures, being buried on ancestral soil is not just tradition, it is a profound expression of belonging.

“It’s one of the most respectful things,” John Degory, the Deputy Chief of Mission at the American Embassy in Fiji, told the Times, describing the repatriation as symbolic of strong ties between Fiji and the United States.

Vendovi Island, in the San Juan Islands off Washington State, was named by American naval officer Charles Wilkes after Ro Veidovi, the Fijian chief he took prisoner in the 1840s. Photo/San Juan Preservation Trust Archive

“We can build on this partnership and may his memory be a blessing.”

But buried within the burial are questions of history and power.

The government says Ro Veidovi was taken from Fiji in 1840 after being arrested aboard the US naval ship USS Peacock and tried at sea over the deaths of American beche-de-mer traders on Kadavu Island.

Many today question the fairness of his capture and trial, suggesting he may have been used as a pawn amid early power plays by foreign navies in the Pacific.

Decades after his death in 1842, Ro Veidovi’s story lives on in unusual ways. An island in the San Juan Islands off Washington State is named Vendovi Island after him, a lasting if unusual reminder of Fiji’s early encounters with the US.

For his descendants and clan members, not all details of his life were vividly passed down, but the weight of his return still stirred deep feelings.

“We know that he was our chief in the 1800s, but the story of his life we don’t clearly know,” Peniasi Qoloutawa, a member of Ro Veidovi’s clan, tells the Times, underlining how oral histories carry both memory and mystery.

For many in Fiji and across the Pacific watching from afar, the moment resonated beyond history books and museum displays. It was about healing a long-standing separation between a chief and his land.

After over 180 years, Ro Veidovi’s journey home served as a reminder of the enduring ties between place and identity in the Pacific, and the power of communities to bring their own histories back into the light.