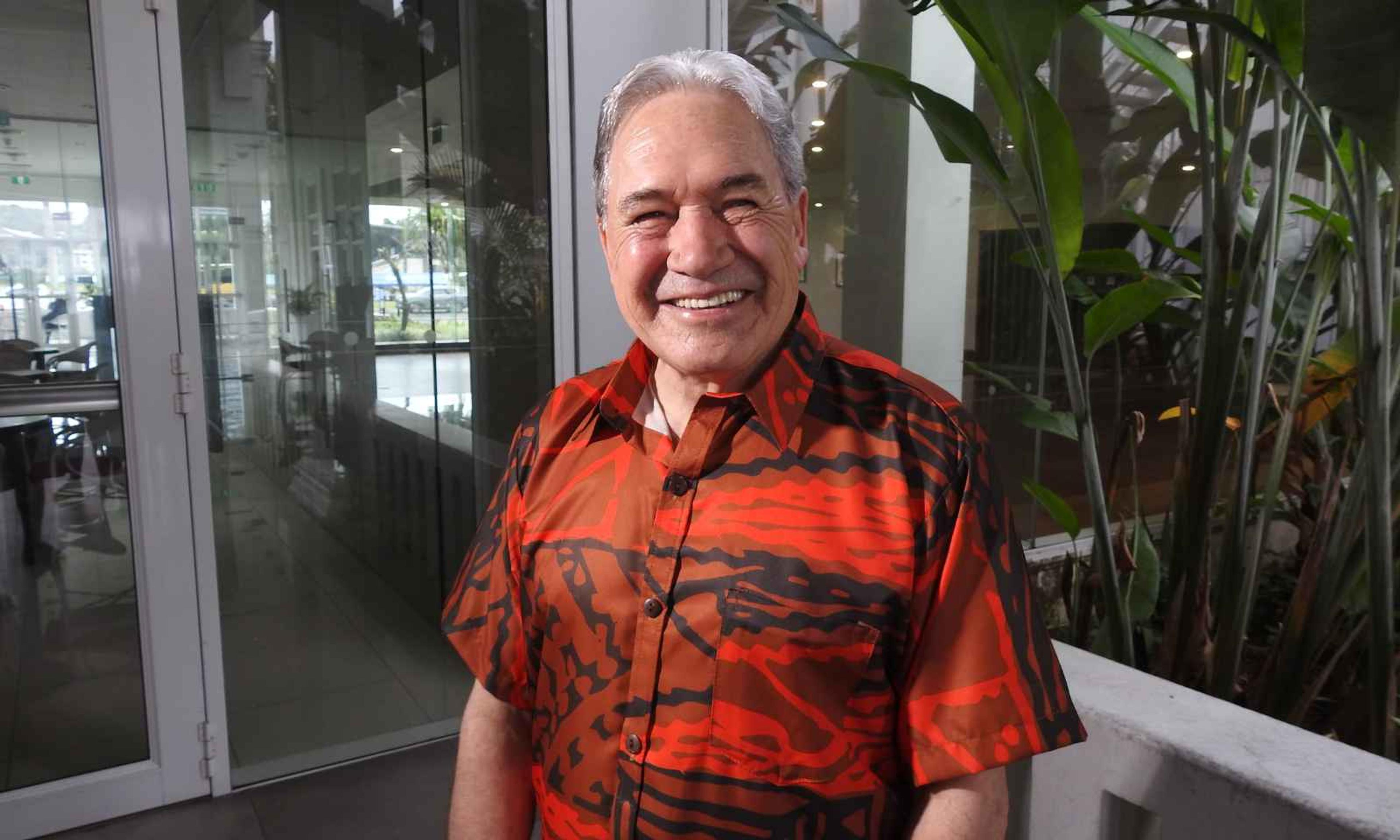

Sylvia Cocker, Citizens Advice Bureau Papatoetoe coordinator, urges people to have conversations before a loved one dies.

Photo/PMN News/Khalia Strong

Cultural traditions leave families vulnerable after the loss of a loved one

Advocates say raising the threshold will ease pressure on Pacific and Māori families, who often face difficulties when cultural inheritance practices clash with New Zealand law.

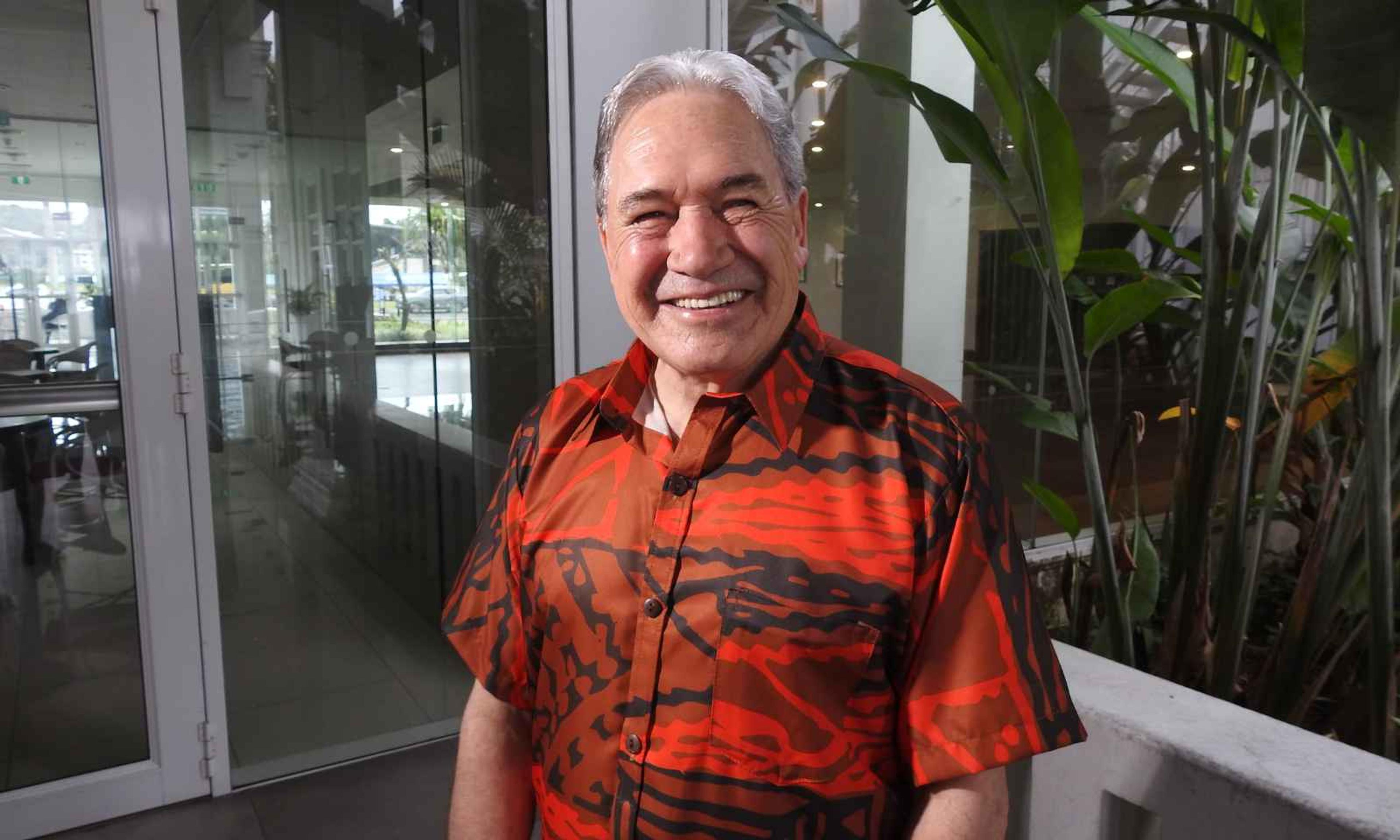

Winston Peters signals support for visa-free travel petition for Pacific nationals

‘The region needs to care about statistics’: Expert on tackling inequality through data

Winston Peters signals support for visa-free travel petition for Pacific nationals

Community advocates and academics warn that some families are at a higher risk of facing legal and financial challenges after a loved one dies.

Sylvia Cocker, coordinator of the Citizens Advice Bureau Papatoetoe branch, says cultural traditions lead many Pacific people to believe that inheritance happens automatically.

She says tensions run particularly high in blended families.

“In most Pacific islands, if your partner or your father passes away, straight away the eldest son would inherit everything, because that's how it's done in Tonga,” she says. “When we come from the islands, we bring the same idea here, not knowing that New Zealand has a process for everything.

“If you have a first wife with kids and a second wife with kids, a family war is bound to happen because each family would like to do it their way.”

Dr Alexander Stevens II, a Senior Māori Academic at Auckland University of Technology’s School of Acute and Primary Health, says traditional inheritance in Māori families goes beyond material possessions.

“Inheritance isn’t just about money or property, it’s also about passing on family roles (and titles), responsibilities, and connections to the land. Things like taonga (treasured items) or land might be passed on based on whakapapa (genealogy), age, or the person’s role in the family or community,” he says. “There can be tension between the legal system (law) and tikanga (lore), especially if they lead to different outcomes.”

Upcoming changes to probate threshold

Currently, if someone dies without a will and has more than $15,000 in assets, the High Court must oversee the distribution of funds to ensure that they are not misappropriated due to dishonesty, fraud, or do not follow the deceased person’s wishes. An estate can include bank accounts, KiwiSaver funds, and personal possessions.

Cocker says this also creates long delays for families, as the funds can be consumed by court costs.

“It will take months, depending on the High Court, as there’s a backlog … it could take up to two years. They’re going to have to accrue more debt paying lawyers’ and legal fees, just to get that little amount. And if they get it, they won’t be able to cover anything at all.”

Waikumete Cemetery. Photo/Auckland Council

In July, Justice Minister Paul Goldsmith announced that Cabinet had approved raising the probate threshold for court approval from $15,000 to $40,000.

In a statement, he says, “Most estates now include KiwiSaver balances well over $15,000, but still have to go through the High Court process. This results in a significant proportion of smaller estates being eaten up in court costs and legal fees.

“Executors need to be able to distribute lower-value assets, ensuring more of an estate goes to the beneficiaries, helping grieving families. The last thing they need is a costly legal process with extra paperwork to deal with.”

The changes will take effect on 24 September 2025, and Stevens says this will help many families.

“The raised threshold means smaller estates under $40,000 can be managed without court involvement, saving families money. This is particularly impactful for Māori and Pasifika whānau and aiga, who may have limited disposable income.”

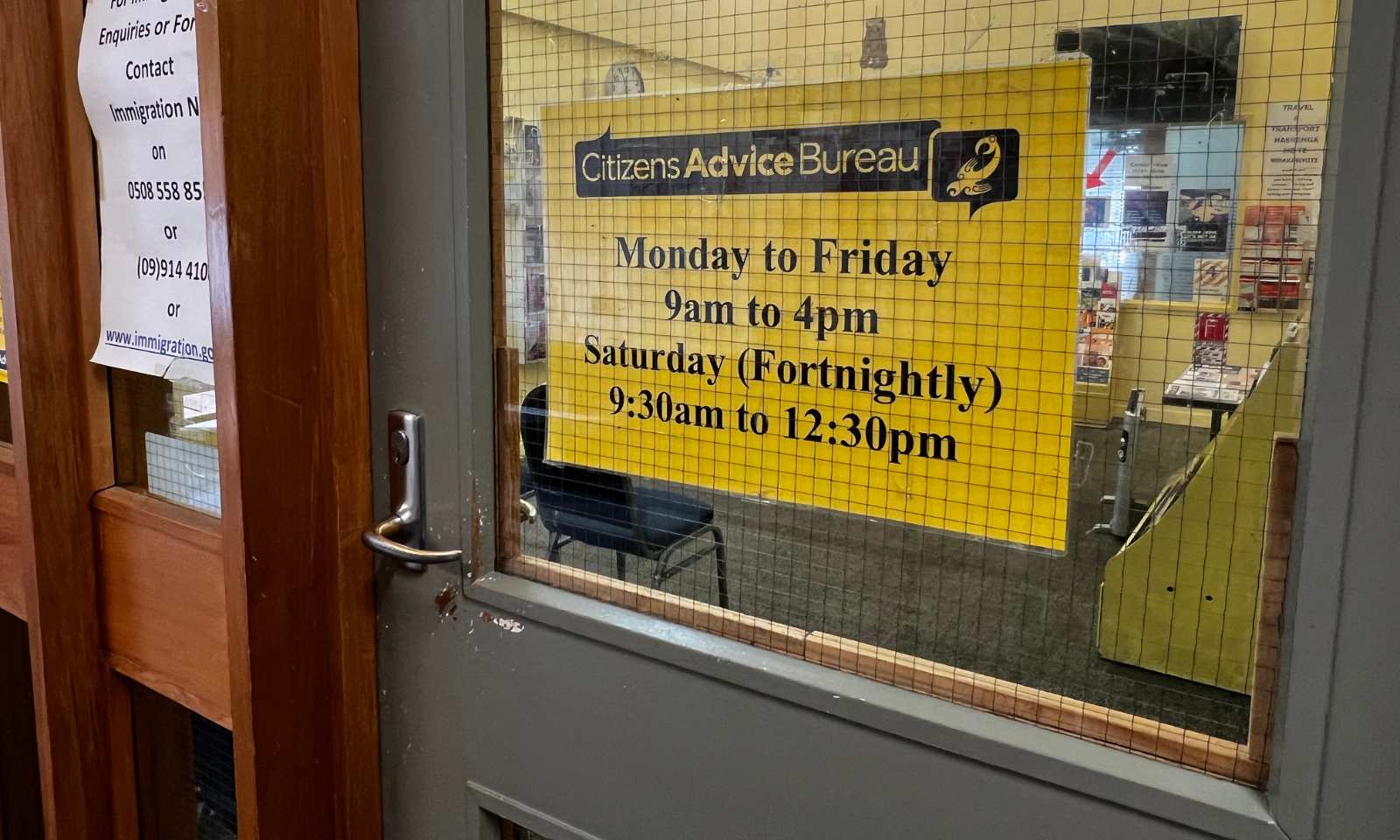

There are more than 80 Citizens Advice Bureau branches across the country. Photo/PMN News

Legal matters and cultural expectations

Cocker says Pacific families also face pressure to meet cultural expectations around funerals.

“Tongans cannot bury their deceased without a pastor or a priest because … the belief is if there's no priest or pastor to do the process, your deceased is not going to heaven.

“You have to prepare an envelope of money to give to the pastor and the church and the congregation,” she says. “Then we have our Tongan traditions with fine mats, which are not cheap, around $1000 to $4000, and you have to prepare the nicest one for the church to take.”

She says younger generations who suggest more affordable options are often met with outrage, and some families would prefer to borrow from loan sharks than break these traditions.

Cocker says people are also wary of potential scams when seeking help.

“These are people in very trustworthy positions. In one case, they ended up transferring their KiwiSaver to the [scammer’s] own bank account, or they had been lied to about how much KiwiSaver they had. We have people that come to the Bureau with receipts of what they're paying people to help them, but later found out they’d been scammed.”

A burial package, including a coffin and funeral service, can cost families thousands of dollars. Photo/Unsplash

Stevens says financial advice on retirement and drafting a will can also be accessed through resources like Sorted.org.nz and Community Law NZ.

“Some charitable organisations also partner with online platforms to offer free or discounted will-writing during limited-time campaigns. Free and low-cost templates are available online for those with straightforward needs, making it easier for individuals to create a legally valid will without needing to engage a lawyer. However, it's best to seek legal guidance, so start with your local Citizens Advice Bureau.”

A change of tradition

Each year, the Citizens Advice Bureau receives about 6000 inquiries related to death, dying, and estates, providing support on issues such as immigration, KiwiSaver hardship withdrawals, tenancy, and budgeting.

Rabia Banu, chair of the bureau’s Māngere branch, says death remains a taboo topic in some cultures.

“They think if they talk about death, they will die quickly. But having a will simplifies life for those left behind when a person dies, helping avoid misunderstandings and unnecessary arguments in the family.”

Banu says in the Muslim faith, burial arrangements are handled quickly. “They pay the council fees, wash the body, dress the body, and it’s taken for the funeral. If the family is really poor, they have the option of paying it back little by little. Or if someone doesn’t have any dependents, it’s free.”

While Work and Income offers a maximum funeral grant of $2616.12, Banu says access to these funds needs to be made simpler, taking into account culturally relevant funeral-related expenses.

Both Cocker and Banu agree that changes are necessary to prevent families from falling into debt. They are advocating for cheaper or free will-writing services, simplified legal processes, and increased availability of information in Pacific languages.

Rabia Banu is chair of the Māngere branch. Photo/PMN News

“The process and the service of writing up a will should be publicly funded,” Cocker says. “Because they have to see a lawyer or Public Trust to do that, it costs money. That's what’s pushing them away, because of how expensive it is.”

Banu says it is never too early to start planning. “As soon as you start a job and you start earning, you should prepare a will. If your life circumstances change: you enter into a relationship, a child is born, you travel overseas, be prepared.”

Cocker offers clear advice for Pacific families: “Look at low-cost burial or cremation options, be prepared, save for a rainy day, and write a will.”

Public Trust offers online will kits ranging from $85 to $219.

Dying Matters Awareness Week in New Zealand runs from 1-7 September, featuring events, workshops, and resources to help families navigate important conversations and decisions.