Pregnancy places major stress on the heart, and specialists warn that gaps in cardiac care are putting some women, especially in rural communities, at risk.

Photo/Raising Children Network

Gaps in heart care put pregnant women in danger, experts warn

Dr Sarah Fairley says uneven access to specialist heart services is putting mothers and babies at risk. And Pacific women could be hit the hardest.

New generation of Pacific midwives strengthens Wellington maternity care

Pacific heritage heralded a strength with Rennie at All Blacks helm

Music of a disruptor: A masterclass in identity, honesty, and resilience

New generation of Pacific midwives strengthens Wellington maternity care

Pacific heritage heralded a strength with Rennie at All Blacks helm

Music of a disruptor: A masterclass in identity, honesty, and resilience

Pregnancy should be a time of hope. But for some women in Aotearoa New Zealand, it can also carry hidden danger.

A leading heart specialist is warning that gaps in cardiac care are putting pregnant women, especially those outside major centres, at risk of serious harm.

Dr Sarah Fairley, Medical Director of Kia Manawanui Trust - The Heart of Aotearoa and Interventional Obstetric Cardiologist, says the issue is not about a lack of skill, but about access and awareness.

The problem, she says in a statement, is not a lack of expertise. "It is less awareness of what constitutes a high-risk pregnancy, issues with access to streamlined funded services and awareness of the importance of post-partum follow-up for women who have had cardiac issues during pregnancy."

Health experts say pregnancy places major stress on the heart. For women with known or undiagnosed heart disease, that stress can quickly become dangerous without specialist support.

Fairley says women who experience cardiac complications during pregnancy are at an increased risk of heart problems later in life, making follow-up care crucial.

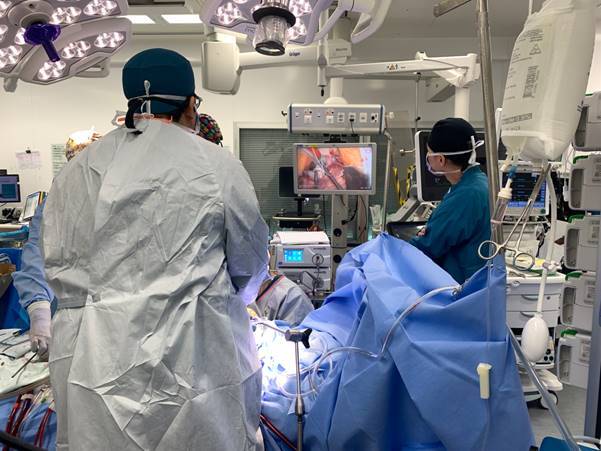

Experts say New Zealand has the expertise to support high-risk pregnancies, but access to specialist Pregnancy Heart Teams remains uneven across the country. Photo/Auckland Hospital Foundation

She says this includes conditions such as pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, hypertension, and fetal growth restriction.

International guidelines recommend what are known as Pregnancy Heart Teams, specialist groups that support women before, during and after pregnancy.

While some major hospitals in New Zealand have these teams, access is uneven.

Health advocates warn that where a woman lives can determine the level of cardiac care she receives: a “postcode lottery” that may put mothers and babies at risk. Photo/NZDoctor

Letitia Harding, the Trust Chief Executive, says where a woman lives should not determine the care she receives.

"Right now, some women get world-class multidisciplinary care, and others don’t - not because their risk is different but because of the postcode lottery," she says in a statement.

"Delays and ad-hoc referrals can have life-threatening consequences for both mother and baby."

For Pacific families, this warning carries extra weight. Pacific communities already face higher rates of conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure, both risk factors for heart disease and pregnancy complications.

Many Pacific families also live in crowded housing or areas with limited access to specialist services.

For Pacific families, protecting mothers is about more than medicine. It is about safeguarding the wellbeing of entire communities. Photo/Rotary South Pacific

In an interview with William Terite on Pacific Mornings, Soteria Ieremia, the co-director Pacific at Pūtahi Manawa, said: “Cardiovascular disease worldwide is the leading cause of death, particularly for our people Māori and Pasifika. We have a much heavier burden than other populations."

Emerging researcher Jackson Murphy-Winterstein also told Terite: “By speeding up our genetic research, we're putting more research out there that is then available for people who are developing treatments and medications.

"And with more research, we have more vast medications. And with more vast medications, we're able to cater to the issues and additional sorts of diseases that may come along with a particular heart disease.”

Health experts say pregnant women in rural New Zealand face particular risk because there is no clear, nationally consistent pathway to access specialist heart care.

“The importance of setting the scene for our Pacific population, ensuring that our Pacific young people can come up through these areas of Pacific research excellence and contribute to the solutions that we need, is just an incredible thing for us to be doing across New Zealand and internationally,” Ieremia says.

Watch Sote-reea Ieremia and Jackson Murphy's full interview below.

As Dr Collin Tukuitonga, Associate Dean Pacific at the University of Auckland, has previously said in reporting on Pacific health inequities: “We know that Pacific people experience higher rates of many long-term conditions, and we must design services that meet their needs.”

Community leaders have long raised concerns about unequal access to care. Gerardine Clifford-Lidstone, Secretary for Pacific Peoples, said in a previous housing and wellbeing report: “These homes are more than buildings, they are places where children will grow, where parents can plan for the future, and where communities will thrive.”

Health experts say the same principle applies to healthcare: safe mothers mean stronger families.

Harding adds women outside major centres face particular risks because there is no clear, nationally consistent pathway to access specialist heart care.

"That is why the Trust is calling for a nationally mandated referral pathway so women with known or suspected cardiac risk can access care rapidly, no matter where they live."

Globally, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in women. For Pacific communities, where family sits at the centre of life, protecting mothers is not just a medical issue, it is a community issue.

When gaps in care leave women vulnerable, the effects ripple through entire families.

The message from heart specialists is simple: the expertise exists, but the systems must catch up. Because when it comes to Pacific mothers and babies, there should be no postcode lottery.

This story has been updated to correct Ieremia's first name Soteria and not Sote-reea as published earlier. We regret the error.