"When given the choice between being right or being kind, choose kind."

Photo/Sariah Magaoa

Walking backwards into the future: Reflecting, relearning, and reconnecting

PMN multimedia journalist Atutahi Potaka-Dewes on her journey to re-indigenising herself.

From the friendly isles to Koroneihana: The Tongan hairstylist trusted with a Queen

Ancient DNA shows how Pasifika carried pigs across the ocean

Pacific Warned: Global powers will act if island nations remain weak

From the friendly isles to Koroneihana: The Tongan hairstylist trusted with a Queen

Ancient DNA shows how Pasifika carried pigs across the ocean

As another year on the Gregorian calendar arrives, the “new year, new me” posts are filling up my newsfeed.

I’ll admit that I used to be one of those people.

But if I’m being honest, a few months would pass, and I would have already broken my New Year’s resolution. I realised that I didn’t actually like the idea of reinventing myself.

Keeping up with that expectation was exhausting. Before the Covid pandemic hit, I decided to turn to my ancestral teachings to find ways to ground myself better.

Like the Māori whakataukī or proverb says, “Titiro whakamuri, kia anga whakamua” (Look to the past in order to move forward).

I grew up totally immersed in te reo Māori, and my kura followed Te Aho Matua (a philosophy of learning and teaching principles). We learned holistic ways of caring for the land, water, people, and spirit, and much of our education was centred around Māori astronomy, such as Matariki.

Our little family unit is four generations strong.

I was raised by my grandparents, who were staunch in their Anglican and Catholic beliefs. So, yes, Christmas, New Year, and Easter were common celebrations in our home, just as much as Halloween.

Koro (grandfather) was a historian, actor, activist, and teacher of Tino Rangatiratanga. He also followed an Indian spiritual master and was very ritualistic with chants, prayers, and karakia.

My grandmother sat on every governance table in Te Arawa and would tell me ghost stories before bed. Nan is a firecracker; she’s vocal, a feminist, and a rebel at heart.

They taught me gentle strength and intentional love and that Māori are not above anyone; we are definitely not at the bottom of the heap either.

Marae were my playgrounds, and during tangihanga (funerals), tikanga and kawa (customs and protocols) would determine my behaviour.

So, you could say I had an eclectic upbringing.

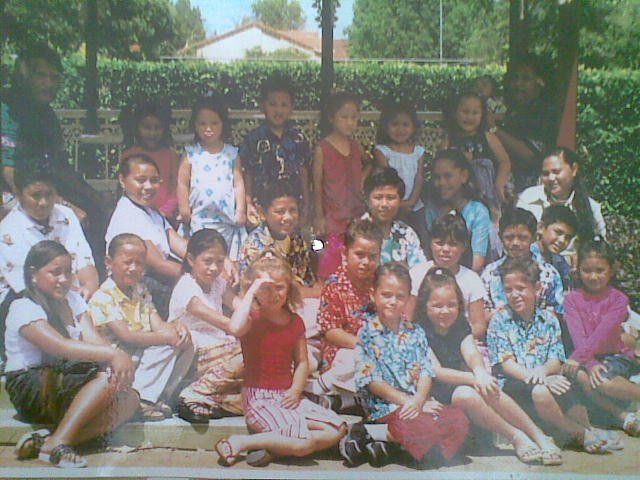

That's 11-year-old me in blue, second row from the back, and second one in from the right.

When I was 10, I moved to Brisbane with my parents and had to adapt from being an only child to the oldest of eight. I was overwhelmed and overjoyed to be a part of such a strong family unit.

My Sāmoan family were devoted members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS), and within a few months, I had converted too. It felt like the spiritual teachings from my childhood had become distant memories.

There are no marae in Logan City, so my Māoritanga took a backseat, and I didn’t even realise that my name could be mispronounced until I enrolled in a mainstream school.

The Fa’a Sāmoa way taught me obedience and reverence. I learned to dress respectfully and was shown my place in the family hierarchy.

But behind closed doors, drugs, alcohol, violence, and abuse were daily visitors. These were shameful secrets that the few who knew worked hard to keep hidden.

Most of my cousins were born and raised in Australia, and when they were spoken to in gagana Sāmoa, they responded in English. I barely spoke either language, so I learned to blend in.

I vividly remember a big family New Year’s lunch where I was asked to bless the food. When I started in te reo Māori, people sniggered, and someone whispered in my ear, “English”.

I went from being the Māori girl who connected deeply with everything around her to the Māuli girl with a long name in a foreign place.

Back then, I didn’t know many afa kasi or people with mixed heritage, and as a result, not many understood how those worlds could coexist. There wasn’t any nurturing guidance to help me understand cultural values. Not everyone was like my Koro and Nan.

There was no transitional period between what was and what is - between who I was and who I was expected to be. It wasn’t a choice. I was told, “This is who you are now”.

I grew accustomed to masking and hiding my real feelings. Maybe that’s why I struggle with the notion of a “new year, new me”.

Frankly, I carried so much hurt from my Sāmoan side and suppressed it all through my teenage years into my twenties. When I returned to Aotearoa, I had forgotten much of my reo and felt defeated.

Performing on the Lincoln Memorial Steps in Washington DC.

I thought I could flush out the ugly feelings by overdosing on dopamine and only engaging in things that made me happy. But chasing temporary gratification only provided superficial happiness.

The pandemic paused my thrill-seeking ways and allowed me to slow down and reevaluate my life’s purpose. I realised that I needed to relearn and reconnect with my indigenous foundations, including both te ao Māori and Fa’a Sāmoa.

I also began therapy.

Moving away from Rotorua has taught me to nurture relationships from my past while living in Tāmaki Makaurau has shown me the importance of making meaningful connections as an adult.

I’m learning to let go of things that have served their time, even if that means releasing some people from my life.

Following te maramataka is beautifully balanced in Māori spaces. But outside of those walls, it’s like playing tug-of-war. The benefit of working in places dominated by individualism and capitalism is that it challenges me to hold strong to my beliefs.

New year, same me.

There are so many strong Pacific knowledge holders around me now that I treat every conversation as an opportunity to learn and hopefully share knowledge in return. There are so many paths that intersect for people of the Moana that I’m having light bulb moments all the time.

As we welcome the Pākehā New Year and find ourselves halfway through the maramataka Māori, I’m walking into 2025 with a good reminder of what it has taken for me to get here. I’m still very much the little Māori girl, and I’m embracing my identity as a teine Sāmoa, too.

Much like the Sāmoan proverb, “E sui faiga ae tumau fa’avae” (Ways of doing may change but the foundations remain the same).

I won’t say “Happy New Year” because, to me, it feels one-dimensional and fleeting, like your true feelings are irrelevant. It feels like a “fake it ‘till you make it” attitude.

So how about instead, let’s go forth and prosper, people.