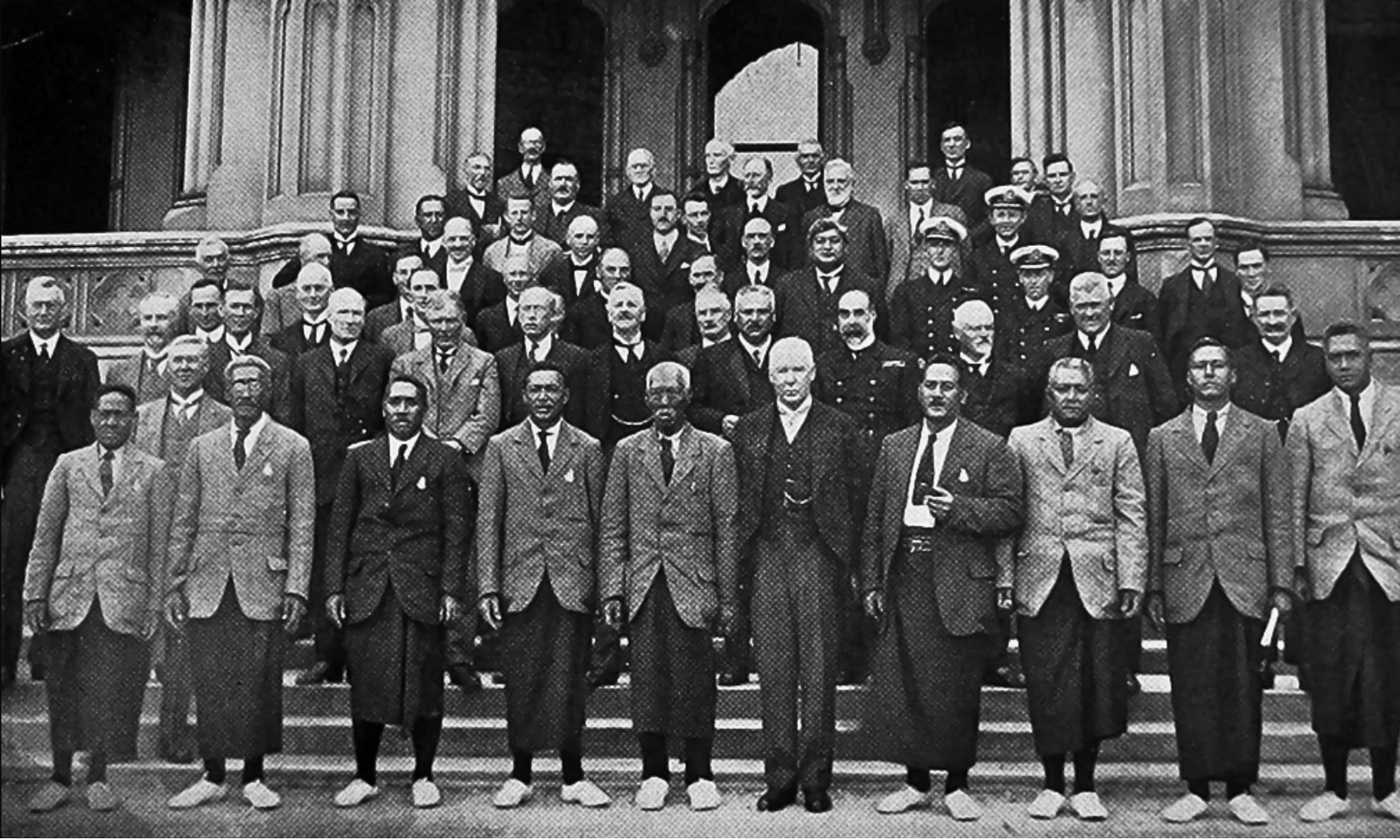

Nine Sāmoan faipule and colonial masters travelling to New Zealand on the Tofua for a carefully staged three-week 'goodwill mission'.

Photo/Published by Otago Witness/A. W. Jones.

NZ-Sāmoan bridge-building: From colonial ‘goodwill’ to citizenship restoration

Exactly 100 years after a Sāmoan “goodwill” tour to NZ, a new citizenship law addresses some colonial harm but fails to completely bridge the divide.

Inspiring coach helping young rugby stars change their lives

Will’s Word: Tory Whanau showed leadership to the end

ADB: Slower economic growth for Pacific amid tourism challenges, global uncertainties

Inspiring coach helping young rugby stars change their lives

Will’s Word: Tory Whanau showed leadership to the end

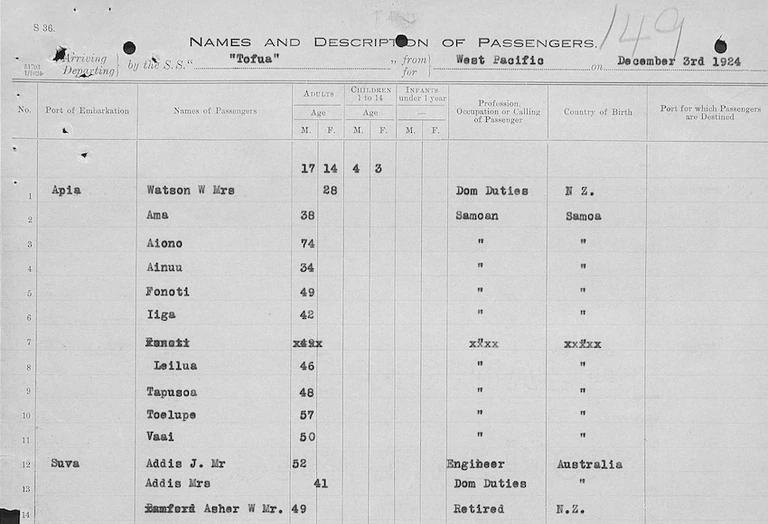

Dressed in what local newspapers called their ‘national kilt’ or lavalava, nine Sāmoan faipule (state councillors) disembarked from a ship in December 1924, stepping into the spotlight of New Zealand.

They were on a three-week tour orchestrated by Major-General George Spafford Richardson, Sāmoa's League of Nations-appointed administrator.

The tour was touted as a "goodwill mission" to mend the frayed relationship between Sāmoa and its colonial overseer.

In reality, the journey was a meticulously staged display of New Zealand's purported "happiness and prosperity", designed to persuade the faipule, and by extension, other Sāmoans, to accept continued New Zealand oversight.

One century later, echoes of that choreographed tour resonate in unexpected ways, particularly as Wellington passes new citizenship legislation aimed at rectifying some of the damage inflicted by the infamous 1982 Act that stripped many Sāmoans of their rightful New Zealand citizenship.

Some hail the new legislation as a partial bridge-building measure because it offers only limited relief: It fails to extend citizenship rights to their descendants or provide automatic pensions for the elderly Sāmoans who take up New Zealand citizenship.

The Sāmoan faipule are hosted to a luncheon at parliament in December 1924. Photo/A.J. Tattersall, ANZ IT9 box 21 7/19.

Compromised bridge-building

The 1924 visit of the faipule served as a bridge-building gesture, albeit a heavily compromised one, as it occurred against a backdrop of colonial mismanagement.

Amongst a long list of examples of colonial ineptitude was the impact of the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918 that led to the deaths of 22 per cent of the Sāmoan population when the New Zealand administration failed to quarantine a virus-stricken ship at Apia

Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Logan's negligent response shattered Sāmoans' trust, and a subsequent royal commission cited "administrative neglect and poor judgement".

Despite this fraught atmosphere, Richardson hoped to showcase how aligning with New Zealand might benefit Sāmoa.

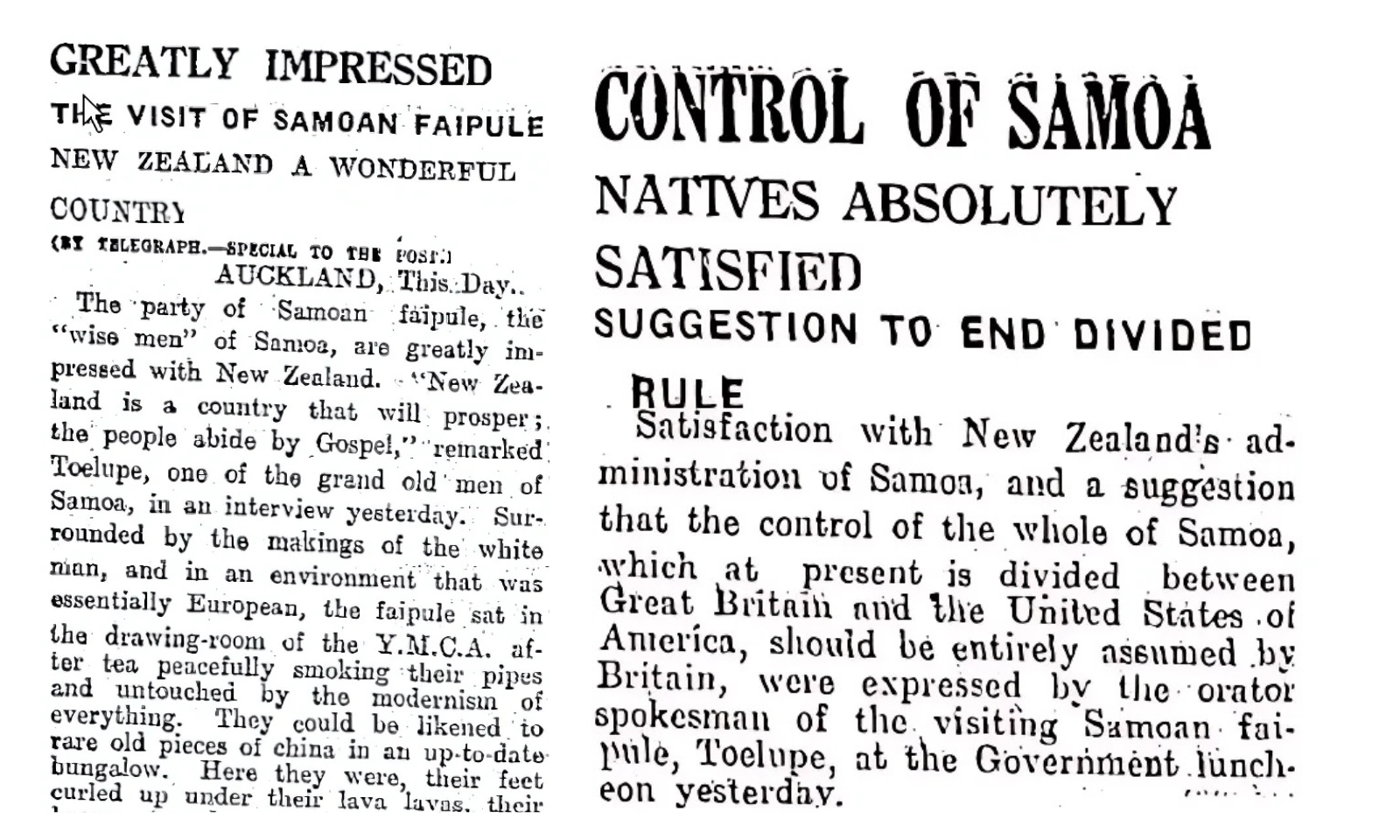

Newspaper reports, including a 26 December 1924 piece in the Auckland Star, dutifully chronicled the faipule’s receptions in Wellington, Masterton, and Rotorua.

Māori leaders in Rotorua, most notably Dr Peter Buck (Te Rangi Hīroa), welcomed the Sāmoan visitors as part of the broader Polynesian family.

Newspaper coverage from December 1924, including these headlines from the Evening Post, suggest the goodwill tour was successful as a PR exercise. Photo/National Library/Papers Past.

Buck invoked shared wartime sacrifices, removing the German flag from Sāmoa during the Great War to highlight supposed bonds of unity.

Yet, beneath the fanfare lay a strategic motive: all nine faipule had been personally selected by Richardson. Their perspectives, popular or not, were deemed the “official” Sāmoan voice by colonial authorities.

Traditional leaders and grassroots activists back home, many of whom longed for genuine self-determination, had little to no say. Although they would eventually prevail when Western Sāmoa became an independent nation in 1962.

Real people with real aspirations

Meanwhile, the 1924 tour was designed less to listen to Sāmoans and more to soothe and shape public opinion in New Zealand.

It introduced many New Zealanders to living, breathing Sāmoan voices, shifting the narrative from tropical outpost to real people with real aspirations. Some even hoped for a time when Sāmoans could have their own seats in the New Zealand parliament, alongside their 'Māori cousins'.

The 1924 passenger's manifest of the faipule who travelled to NZ. Photo/Supplied.

For some Sāmoans, it was the first time their concerns had been aired before a broader public, even if they were filtered through the lens of colonial authority.

Fast-forward to 2024, and thanks to Green Party MP Teanau Tuiono, the New Zealand Parliament has unanimously passed legislation that restores New Zealand citizenship to individuals born in Western Samoa between 13 May 1924 and 1 January 1949, who were not in New Zealand in 1982 and whose citizenship was removed by the 1982 Citizenship (Western Samoa) Act.

The new law, while a step towards reconciliation, echoes the limitations of the 1924 tour.

Just as the faipule's visit was carefully curated to present a specific narrative, the 2024 legislation pragmatically addresses only a subset of those affected by past injustices.

It's estimated that 5000 people may be eligible to apply for New Zealand citizenship under this new law.

Critics argue that because of the law's short-comings, it's a hollow victory. But it's also another admission that New Zealand's past policies were both discriminatory and ill-advised.

Green MP Teanau Tuiono navigates his amended citizenship bill through Parliament which passes its third reading. Photo/PMN News/'Alakihihifo Vailala.

In 2002, New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark formally apologised to Sāmoa for the wrongs committed by the colonial administration.

In 2021, another Labour PM, Jacinda Ardern, apologised to Pacific communities impacted by the 'dawn raids' immigration policy.

Neither apology covered the racist 1982 Act pushed through by the Robert Muldoon government, that the Labour Party also supported while in opposition.

An uneasy partnership

Despite these criticisms, the 2024 citizenship law does demonstrate that conversations, once suppressed or ignored, are finally being addressed at a legislative level.

It underscores a willingness to acknowledge the historical injustices Sāmoans faced at the hands of New Zealand officials.

Looking back to 1924, when the faipule were paraded through New Zealand’s towns and cities, we can see another example of this uneasy 'partnership' in action.

Governor-General Dame Cindy Kiro signs the Sāmoa Citizenship bill into law in November 2024. Photo/Facebook.

The goodwill tour was a PR exercise riddled with half-truths. Yet even then, it opened a narrow channel of engagement between Sāmoans and New Zealanders.

That channel, broadened by decades of struggle and advocacy, has led us to this moment, where a new law aims to restore at least some measure of dignity and justice to those hurt by earlier injustices.

One hundred years on, Sāmoa and New Zealand are still negotiating the terms of their relationship.

One plank at a time

The legacy of 1924 reminds us that bridge building often proceeds in imperfect increments, sometimes motivated by political calculation more than genuine empathy.

The 2024 citizenship law carries that same duality: it mends a fragment of the wound inflicted by the 1982 Act while leaving many still disenfranchised.

Yet, the fact that such a law exists at all is progress compared to a time when Sāmoans had little recourse but to rely on a tightly choreographed “goodwill tour” for any hope of being heard.

If the journey of the nine faipule was a tentative step in bridging a divide, then this new legislation, for all its flaws, is another plank laid across that bridge.

So, as we mark the centenary of the 1924 faipule visit and reflect on this latest legislation, let us remember that real healing demands more than surface gestures.

Bridges are built one piece at a time, but they must be solid enough to carry everyone across.

Some articles and photos have been reproduced under the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 3.0 New Zealand licence.