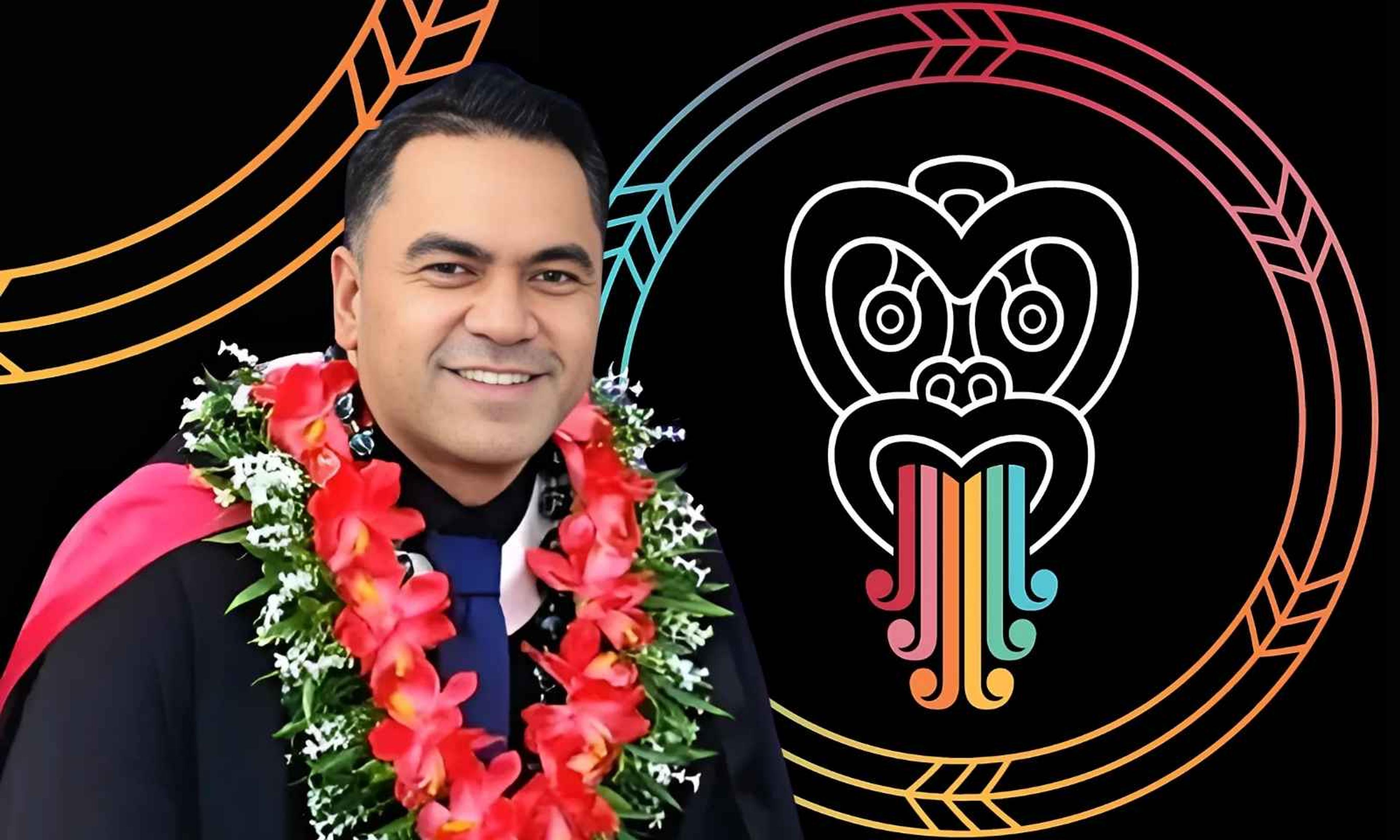

Dr Will Flavell dreams of a day when the Māori language is the main means of communication across the motu.

Photo/Facebook/Will Flavell/Reo Māori

50 years of te Wiki o te Reo Māori: From the loss of language to championing its revival

As we mark 50 years of Te Wiki o te Reo Māori, Dr Will Flavell reflects on his and his family’s journey with the Māori language, urging Aotearoa to embrace te reo everyday.

Celebrating Fijian Language Week: Honouring identity, culture and connection

Will’s Word: Why we might be writing off leaders too quickly

Mils Muliaina joins Auckland Business Chamber as first Pasifika director

Green MP questions Sāmoa shipwreck payout, warns peace declaration at risk

Celebrating Fijian Language Week: Honouring identity, culture and connection

Will’s Word: Why we might be writing off leaders too quickly

Mils Muliaina joins Auckland Business Chamber as first Pasifika director

Te Wiki o te Reo Māori has begun across Aotearoa, marking 50 years of the nationwide movement dedicated to revitalising and celebrating the Māori language.

This year's Māori Language Week celebrates half a century since New Zealand first recognised Māori Language Day in 1972, following a petition signed by more than 30,000 people calling for te reo Māori to be taught in schools.

By 1975, the event expanded into a week-long celebration. This year’s theme follows from previous years, which is “Ake ake ake - a forever language”. The weeklong event ends on Saturday.

Led by Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori, this week encourages people across the motu to embrace and use te reo Māori through community events, online campaigns, and educational activities. Celebrations include a reo parade along the Wellington waterfront, a webinar series, and the launch of Pūtahi Mahara, a digital time capsule for messages to be opened in 2075.

Speaking with Tofiga Fepulea’i on Island Time, Dr Will Flavell (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Whātua, Ngāti Maniapoto) acknowledges the 50-year milestone. Flavell is an Auckland councillor for the Henderson-Massey Ward and a long-time advocate for te reo Māori.

He points out that there are still obstacles to overcome, some of which inspired his doctoral research in exploring why many non-Māori students choose to learn te reo, showing that it is a language for all New Zealanders.

Te Wiki o te Reo Māori marks 50 years of the country’s movement dedicated to revitalising and celebrating the Māori language. Photo/Reo Māori

“Other challenges we have is te reo Māori being used as a political football. Every election time, particularly central politics, we constantly see te reo Māori kicked around. Our rangatahi [youth] see that,” Flavell says.

“They notice when our community or national leaders are hurling abuse at te reo Māori, or not recognising its importance. Our young people are saying, ‘hang on, what are you doing? Why are you treating te reo Māori like this? It's a taonga for all of us’.

“So 50 years since te Wiki o te Reo Māori was made a language week, and we've still got many more hurdles and challenges.”

Watch Dr Will Flavell’s full interview below.

He says his passion for revitalising te reo Māori was shaped by his whānau’s history, explaining that his parents and grandparents do not speak Māori.

“No fault of their own. Back in the days, the Government pushed for English first. My grandfather's generation would be physically punished if they ever heard te reo Māori spoken in the playground or at school.

“That’s why he didn't have the reo. That carried on with my parents' generation. My generation, myself and my siblings, thought te reo is central to our identity so it's important for us to normalise te reo Māori back in our whānau.”

As a councillor for 12 years, Flavell has helped implement bilingual announcements on Auckland trains and buses, and worked with mana whenua to restore authentic Māori names for streets, parks, and reserves.

He recalls a conversation from a decade ago where he questioned why European public transport systems operate with announcements in three different languages while Aotearoa did not have te reo Māori.

“They first said to me, ‘we can't do that, Will, that's way too hard’. But I kept pressing and pressing, and finally, we got it done. I want the Māori language to be a language that's accessible in the community and public spaces.”

Tamariki at te Wiki o te Reo Māori parade in Wellington, 2019. Photo/RNZ/Rob Dixon

Flavell encourages whānau to start their reo journey at home by using language apps, practising karakia and labelling everyday household items with their Māori names. Looking ahead, he hopes to see a future where te reo is used naturally in daily life.

“I've got big hopes and dreams for te reo Māori. I have hopes that I could visit my doctor and I could ask them what's wrong with me in te reo Māori. I could go to the fish and chip shop and order in te reo Māori.

“I could go to the pharmacy and chemist to get my medicines and use te reo Māori as the main means of communication. That's my hopes and dreams about really naturalising and normalising te reo Māori throughout our community.”