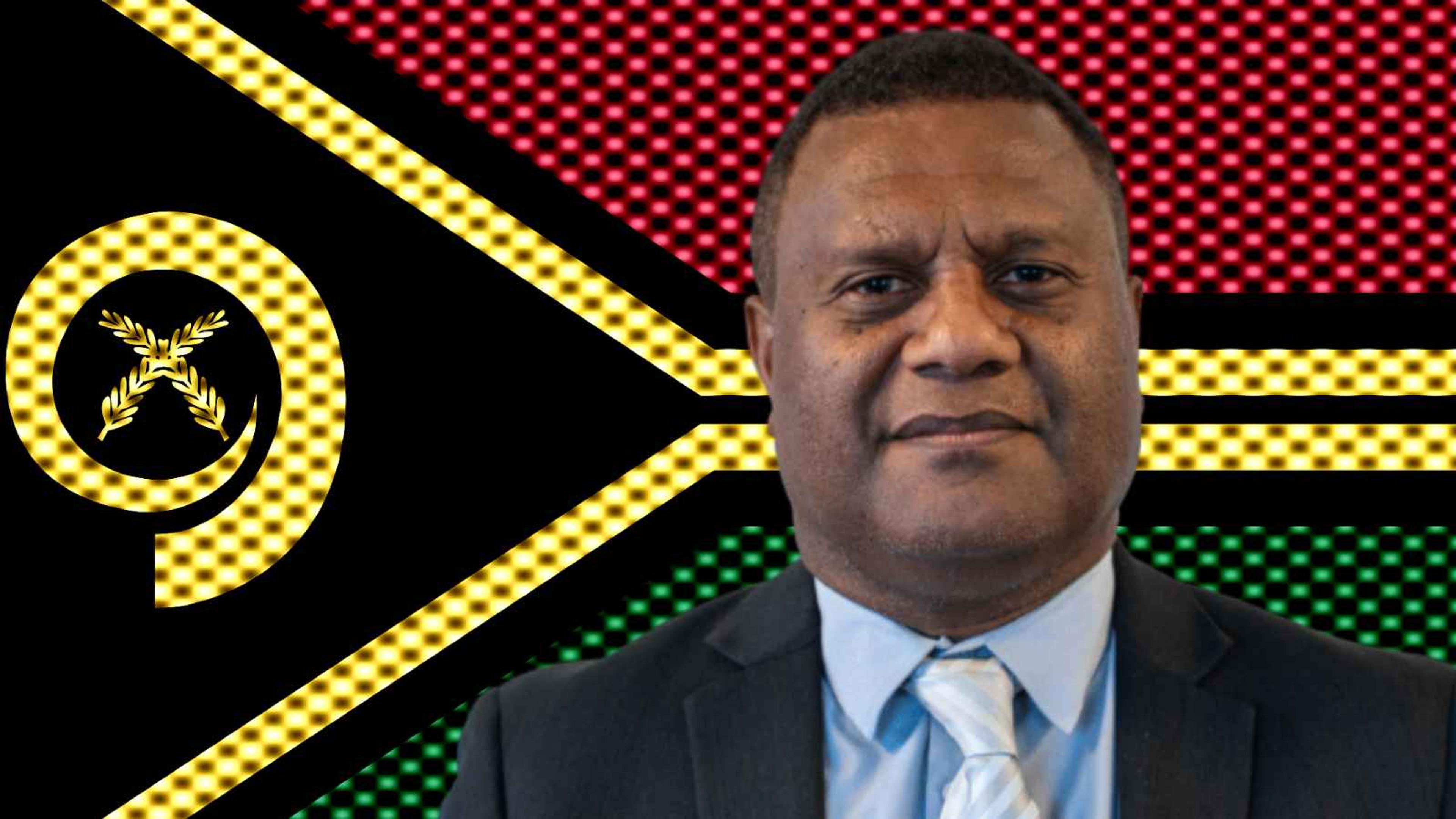

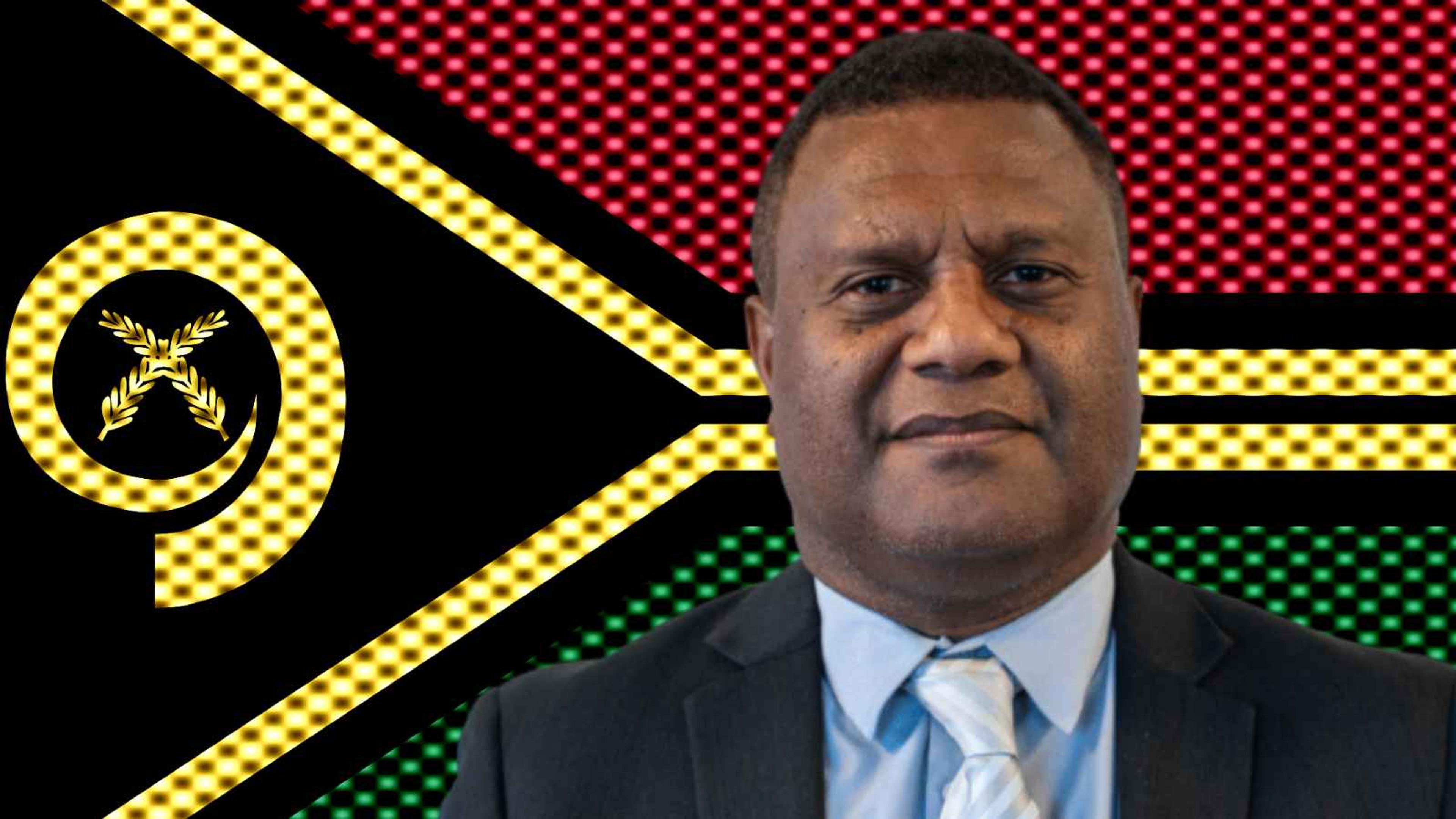

Dr Sonny Natanielu advocates for unity beyond national boarders when discussing shared Pacific knowledge and ancestral links.

Photo/RNZ

‘It was ours as an extended family’: Tatau, Pacific kinship, unity

Amidst the Tongan tatau controversy, Dr Sonny Natanielu challenges modern national divisions, urging stewardship and oral history.

Manurewa charity requests $30,000 to keep Pacific seniors monthly gatherings

Blacklisting squeeze hits Vanuatu families and businesses, the regulator VFSC warns

Pageant talk: Pacific queens on colourism, transparency, and online backlash

Manurewa charity requests $30,000 to keep Pacific seniors monthly gatherings

Blacklisting squeeze hits Vanuatu families and businesses, the regulator VFSC warns

Discussions about the origins of tatau have been going on for decades, especially during various revival stages of Pacific cultural practices and traditions.

Recently, the concept of a “Tongan malu” has caused controversy online after two women - both of Sāmoan and Tongan heritage - received a tatau featuring Tongan motifs and symbols.

Cultural consultant Dr Sonny Natanielu, who holds a PhD in Sāmoan traditions related to tatau, argues for a broader approach to nationhood in this discussion.

“The divisiveness that’s in the discussion is, ‘It’s a Sāmoan this, it’s a Tongan that’.

“So the question for me is, who is a Sāmoan that they are entitled to or not entitled to whatever is the clear Sāmoan?

“If we let these western national boundaries tell us who is a Sāmoan, then that’s where I think we get into trouble.”

Natanielu says the arbitrary borders imposed by Western powers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries have divided the Pacific people, disregarding their deep genealogical ties.

He advocates for genealogical and ancestral definitions of identity rather than the nationhood imposed by Western ideologies.

“Ancestrally, genealogically, they are us. We are them.”

Western national boundaries vs genealogical ties

He further explains the historical relationship between Sāmoa, Tonga, Tokelau, and even the Solomon Islands, highlighting the complex ties between Tonga and Sāmoa.

“The story of Tonga and Samoa is not one people ruling over another people… The story of Tonga and Samoa is one people divided by class.”

Ian C Campbell, a former history professor at Canterbury and South Pacific universities, supports this view in his book Island Kingdom: Tonga Ancient and Modern.

He discusses the historical unity between Tonga and Sāmoa before European colonisation, acknowledging that while class division played a role, regional and political tensions also contributed.

“A ruling class and a working class. And after a few generations of cruel leaders or dictators, the working class became a slave class. And what history tells us about slavery, rebellion always follows slavery,” Natanielu said.

Shared unity and cultural exchange

He says that historically, Tonga did not possess a distinct “Tongan tatau" as royalty would travel to Sāmoa to receive it since Sāmoa was the primary continuation of the practice.

Natanielu emphasised that tattooing was part of a shared Pacific cultural heritage.

“There was no such thing as a Tongan tatau... It was ours as an extended family of the Pacific... The patterns are seen all over the Pacific.

“Now, the so-called Tongan tatau is a fairly new way of expressing Tonganess… cultures adapt. Cool. And because it's now different, they want to call it a Tongan tatau.”

He connects traditional malu patterns to star maps, symbolising ancient navigational knowledge.

“The original malu was the star map because we all used the star map. We all used the same stars to navigate the Pacific until colonisation brought an end to it.”

Oral traditions vs written traditions

“Long live the written tradition, and long may it continue, and we should read and be literate and all of that. Long may that live,” Natanielu said.

“But beyond that, we also have other ways of storing knowledge, other ways of knowing, other ways of learning.”

Oral traditions prevalent across the Pacific were disrupted during colonisation, as Western educational systems prioritised written records over oral storytelling, systematically marginalising indigenous ways of knowledge transmission.

Natanielu highlights the importance of oral traditions in preserving Indigenous Pacific knowledge while also acknowledging the value of written accounts in academia.

Epeli Hau'ofa.

"In our cultures, we store our knowledge in song and dance, on our bodies, in the stars, in the forest, in the mountains. That's our library. And so if you want to learn about us, you sing, you dance, you voyage, you get a tatau, you spend time in the forest.”

Tongan and Fijian writer and anthropologist, Epeli Hau'ofa, discussed these themes in his essay, "Our Sea of Islands", critiquing the richness of Pacific knowledge systems.

Hau'ofa emphasised how colonial rulers often sought to confine Pacific Islanders, both physically and metaphorically, thus limiting their worldviews and understanding of their heritage.

Natanielu encourages a balanced and shared understanding of both worlds, while he admits his bias leans towards oral history and traditional customs.

“One of the weaknesses of oral traditions (is) once you stop singing, once you stop talking, once you stop sharing stories, you start forgetting."

Held knowledge and the responsibility to share

Natanielu recounts the story of Mau Piailug, a master navigator from Satawal, Micronesia, who shared his navigation knowledge with Hawaiians in the 1970s.

Despite initial resistance from the Satawal elders, Mau recognised the impact of colonisation on Pacific people and chose to teach others.

This initiative led to a revival of traditional navigation practices across the Pacific.

“Imagine if he took that same divisive approach and said, no, we're going to keep traditional navigation to ourselves. If you lost it, that's your fault. It's your problem. It is a Satawali, it's a Micronesian thing. But he didn't do that.”

Pius Mau Piailug. Photo/Twelve Explorers

Unity beyond national boundaries

Natanielu is proudly patriotic but says this should be balanced with unity.

He encourages stewardship over ownership and promotes diving deeper into traditional histories.

He invites everyone to engage in thoughtful discussions, collaborate, and share cultural knowledge.

“Yes, I'm Sāmoan, Manu Sāmoa forever… and long may the Red Sea, the Tongan Red Sea, long may that live. We also have connections beyond those boundaries. And so let's not forget that. Let’s not let these national boundaries divide us.”