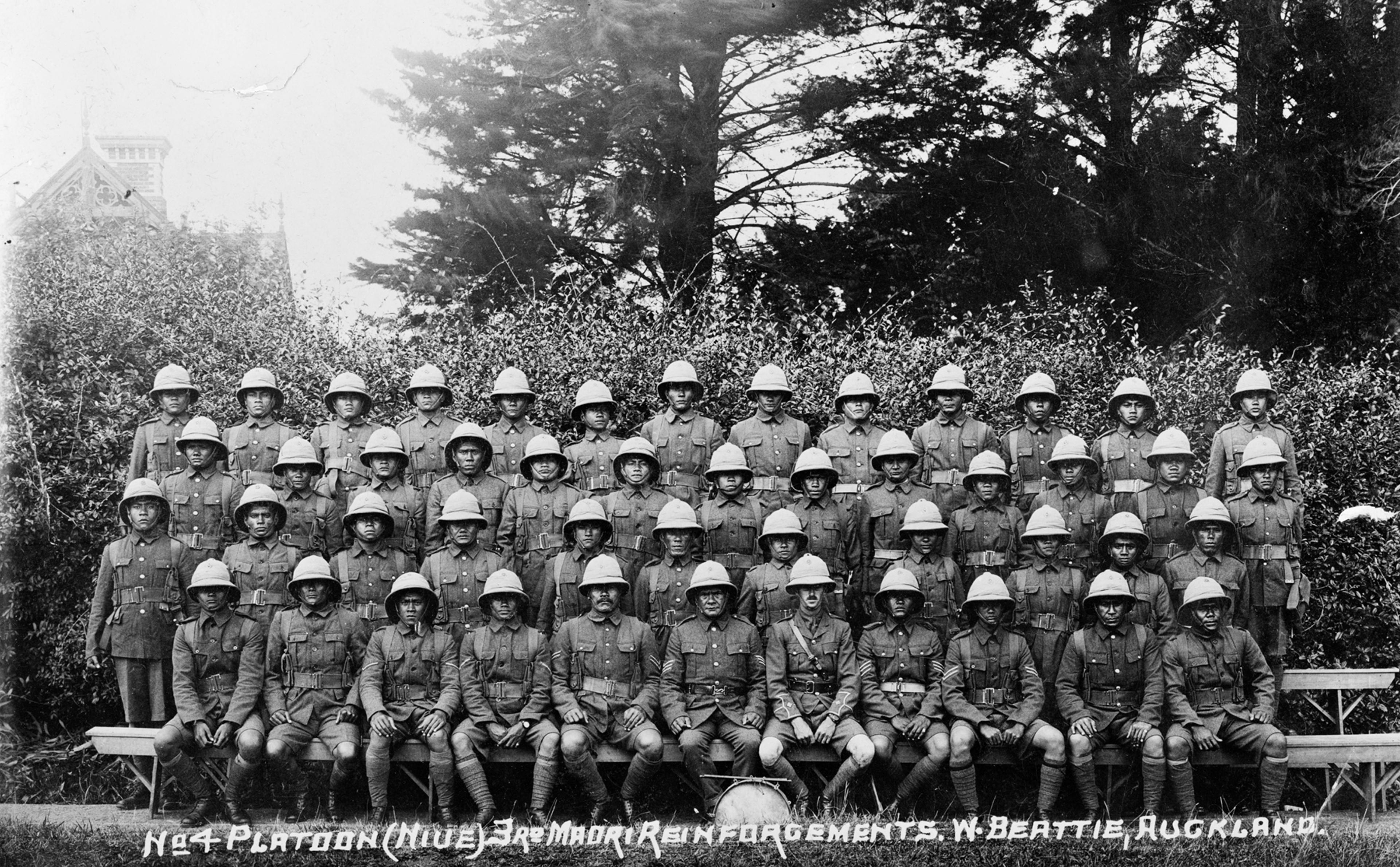

A group portrait of No 4 Platoon (Niue) 3rd Maori Reinforcements, by P J Gordon.

Photo/ Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: 1/2-042997-F.

The Forgotten Soldiers of Niue: My tupuna is buried 17,000 kilometres from his home

My great-great-grandfather was one of one-hundred and fifty soldiers plucked from Niue Island and sent to the frontlines in World War 1 over 100 years ago.

Christmas under the sun: How Pasifika are celebrating amid rising heat, extreme weather

Christmas under the sun: How Pasifika are celebrating amid rising heat, extreme weather

My tupuna (ancestor) is buried over 17,000 kilometres from his home, Niue Island. He was one of 150 soldiers plucked from Niue and sent to the frontlines in the First World War.

Private Mitikele 16/1087 served in the NZ Māori Battalion - Niue contingency. He trained at Narrowneck, Devonport before heading to Egypt on the SS Navua to join the newly formed Pioneer Battalion.

Egypt would become my tupuna’s final resting place for the next 100 years. Private Mitikele died from heatstroke on sentry duty in the fierce Egypt sun.

I often think of these 150 soldiers, my tupuna, their sacrifice in the lead up to Anzac Day and beyond. What was going through their minds? Why did they get on that boat and leave home? Did they think they would ever return?

Those questions manifested in a unique opportunity I was given to feature in a documentary telling the story of our forgotten soldiers.

Untold Pacific History, Season 2, Episode 1: The Forgotten Soldiers of Niue

RNZ’s Untold Pacific History series is dedicated to telling unique histories from the Pacific. The first episode for season two titled 'The Forgotten Soldiers of Niue' is in-depth retelling of the 150 Niue soldiers who fought in WW1.

In the video, there was a group of soldiers re-enacting the experiences of our Niue soldiers experienced over 100 years ago. I was one of them.

I joined my three cousins Topui Junior Talagi-Ikiua, Kenrick Viviani-Tanuvasa and director Leki Bourke-Jackson as three tama Hakupu (Hakupu men) part of this story. We arrived early to a small inlet near Piha beach in West Auckland and put on our costumes.

Getting changed into the costumes, reminiscent of what the soldiers wore in WW1 was quite surreal. Putting on these pale beige, green shirts, jackets, overalls. Heavy boots. At that moment, I thought of our tupuna when they were putting on these gears for the first time.

Some of them had never worn boots, or shoes, never wore these types of clothes. We were asked to line up on the beach, and begin marching looking towards the water. Standing in line, waiting for the director to call action - I was thinking of how our boys would have been.

As we stood there, ten actors were in line, some of us laughing, some silent and serious, I could just imagine how that was for our soldiers hundred years earlier. Despite being thousands of miles from home, the mixed emotions they must have felt became so evident to me.

Sickness strikes Niue soldiers

The documentary also highlights the Niue soldiers' adjustment to the different environment. Due to sickness and death, only 140 of the 150 Niue soldiers would leave New Zealand to Suez, Egypt.

It was many of the Niue soldiers' first time leaving their small island home, and being exposed to the different sicknesses, different climates and different foods, it proved a challenge to adjust.

Moving through Egypt, into France and England, many of the soldiers would fall ill and die. I can’t imagine the completely different world they were exposed to, being plucked from their small island and taken across the world. For all we know, Niue was the only world they knew.

And sickness would be the influencing factor that led to the Niue soldiers being sent back to Niue. Too many of our boys fell sick, or died from sickness, and the decision was made to send them home.

During filming we moved into camping grounds up in the Waitakere Ranges to continue filming. For one scene, we were put into beds and asked to look sick and distraught when the camera came around. Walking into the room of beds, I saw an actress dressed as a nurse from the early 1900s. This part of the documentary brought home to me, the deathly silence it must have been, for the remaining soldiers on their trip back home. Leaving the battlefield confused, maybe sick, probably worried and potentially ashamed.

In the scene where we are all in beds, laying in our war clothes and acting sick, it once again put me in the shoes of our tupuna, who would have been bed-ridden and sick. What was the fear they were going through? Did they regret their decision? What were their final thoughts?

One of the actors would reenact a death scene dying on the bed, we weren’t allowed to look up at him, just lay and stare at the ceiling. Hearing him screaming for help, struggling for air, and the silence that followed - while we were only acting - it suddenly felt all too real.

A nurse tends to a wounded soldier (re-enactment). Photo: Tikilounge Productions / Tuki Laumea

Niue’s involvement in World War 1

Niue received news of the war five weeks after the battle had begun. A vessel carrying newspapers for the small European population delivered the news that war had broken out.

Niue was a former colony of Britain, and was annexed to New Zealand in 1901. The Patuiki (King) of Niue at the time was quick to offer Niue’s support to the Crown’s efforts in the war.

The Togia, Patuiki (King) of Niue's declaration on September 1914 read:

To King George V, all those in authority and the brave men who fight. I am the island of Niue, a small child that stands up to help the Kingdom of King George. There are two portions. We are offering 1. Money, 2. Men.

Two-hundred men were selected to begin training for the war in Alofi and Hakupu. It wasn’t sure if the offer would be accepted by the Crown, but, following the considerable loss of soldiers in the Maori Contingent at Gallipoli - the offer was accepted by Member of Parliament Dr Māui Pōmare to help with reinforcements.

Pōmare arrived in Niue on the 12th October 1915 to collect the Niue soldiers. Inspections were done to see if the soldiers were medically fit to go to war. A church service and several village feasts were put on for our soldiers before going on to the ship.

The men were dressed in the church whites (clothes), and were given a copy of the Niue New Testament bible. Mothers, wives, and families of the soldiers stood at the Alofi Wharf, watching the ship head off into the horizon.

I wonder what it was like for those families standing on the cliffside watching their men go to war. What was it like for those men, looking back at their families, watching their island grow smaller and smaller in the distance.

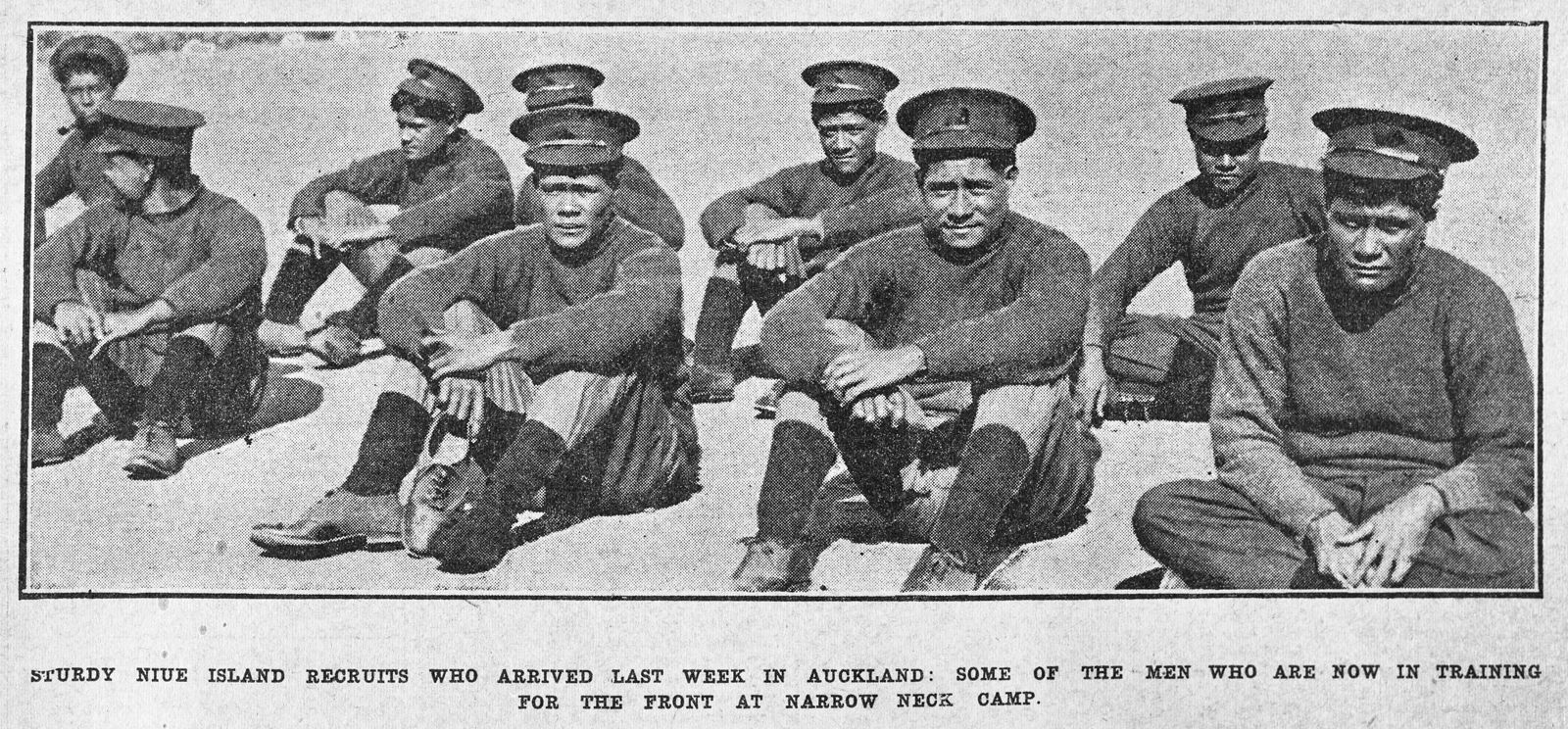

Niuean soldiers while in training at Auckland's Narrow Neck Camp. Photo/Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, reference: 7-A14272.

Legacy

There were several beautiful stories told in the documentary that after 100 years have lived on for these 150 soldiers' descendants to tell. They might have gone to a war that wasn’t there’s to fight, they might have died for a cause they didn’t know - but their legacy of courage has lasted lifetimes.

When I think of war, I think of my great-great grandfather Private Mitikele, who was one of 150 brave young men that had the courage to fight for our freedom. I think of his grandson, my grandfather Ikimaga Manukuo, who would champion Mitikele every year on Anzac Day services.

I think of Mitikele’s mother, my great-great-great grandmother who, upon hearing the news of her son's death, renamed herself “Ikipito” the transliteration of “Egypt” in honour of Mitikele’s final resting place.

Being involved in this beautiful re-telling of the stories of our tupuna, I feel humbled to have felt a glimpse of the world my tupuna lived.

It’s been 108 years since he passed, and while he is buried 17,000 kilometers away from Niue, the stories and memories of Mitikele and the 150 Niue soldiers who went to WW1 still live on and inspire us in the here and now.