Screengrab from Tales of Time - Tama Uli by Oscar Kightley, who is observing photos of indentured Solomon Islanders in Sāmoa.

Photo/YouTube/ TheCoconetTV

Meauli means 'black thing' or does it? How cancel culture can reinforce colonisation

PMN's Aui'a Vaimaila Leatinu'u dives into how the attempt to retire the word Meauli is also an insight into colonisation.

Tackling a health emergency: Pacific Tag tournament raises dementia awareness

NZ-born toddler denied visa despite severe brain injury and faces risk of unlawful status

Sāmoa backs visa-free travel petition as Pacific leaders reject ‘mass migration’ concerns

Tackling a health emergency: Pacific Tag tournament raises dementia awareness

NZ-born toddler denied visa despite severe brain injury and faces risk of unlawful status

During the height of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 various conversations around spotting and eliminating anti-blackness circulated.

Among those important conversations was one on the Sāmoan word meauli which some called a derogatory term for black people.

However, what hasn't been made clear is that some of the attitudes towards the term's cancelation is positioned from a colonial lens. And this colonial view is enacted by both those arguing to keep the term and those advocating it's retirement.

Mea means thing, uli means black

People have translated meauli to mean "black thing", given mea means thing and uli means black, and understandably this led to a flurry of negative reactions.

Auckland University's Sāmoan language lecturer Lemoa Henry Fesuluai says the translation is correct "but that's only one version".

"You're putting a westernised lens on a Sāmoan term without understanding the different layers of that term," he says.

Some have missed that mea means people too depending on the context. Therefore in the context of calling a person meauli a more accurate translation is "black person".

"Mea can be a descriptive term. It's also a noun followed by an adjective," Lemoa says.

An example of this is how titles are referred in honorific reference. One example refers to the title name Sitagata and his family within fa'alupega, or naming of chiefly titles that acknowledges individuals and families' connection to a land and origins of their past.

Lemoa says the title Sitagata refers to the mice the holder travelled with, one being brown, another black and another white.

"So they were given the names Sita'ena for brown, Sitauli for black and Sitasina for white.

"When we use it in that cultural sense and say le measina, le mea'ena, le meauli, we're not using it from a racial stance but referring to those people as that name."

Lemoa says the online reactions of people translating mea solely to thing is likely due to their level of gagana Sāmoa (Sāmoan langauge).

Sāmoan langauge teacher Lemoa Henry Fesuluai. Photo/PMN Samoa

The difference between uliuli and uli

Lemoa says in terms of colour uliuli is more accurate than uli, in which the latter holds various meanings.

"Uli does not only refer to black it also refers to something dark."

Lemoa says Sāmoa's Fa'atuatua ile Atua Samoa ua Tasi (FAST) political party's leader, La'auli Leuatea Polataivao has uli in his name but it isn't about colour.

"It refers to the story where he visited his sister in the night. So uli in his name refers to night.

"There's a lot of connotations, like taro coming from the ground and you see the skin of it is dark then that's fuauli."

Why etymology uplifts indigeneity

Lemoa says from an indigenous viewpoint words depend heavily on context and how the vā is upheld.

"It's about which lens is a person interpreting words from," he says.

Lemoa touches on an important point: The whakapapa, or history, behind the English word thing and the Sāmoan word mea are entirely different.

Therefore comprehending meauli without being saturated in Sāmoan language, culture and history leads to one-dimensional translations.

That brings us to the etymology of meauli

It's speculated that Meauli originated during Germany's occupation of Sāmoa in the early 1900s to describe the Solomon Islanders being brought to Sāmoa to work on plantations.

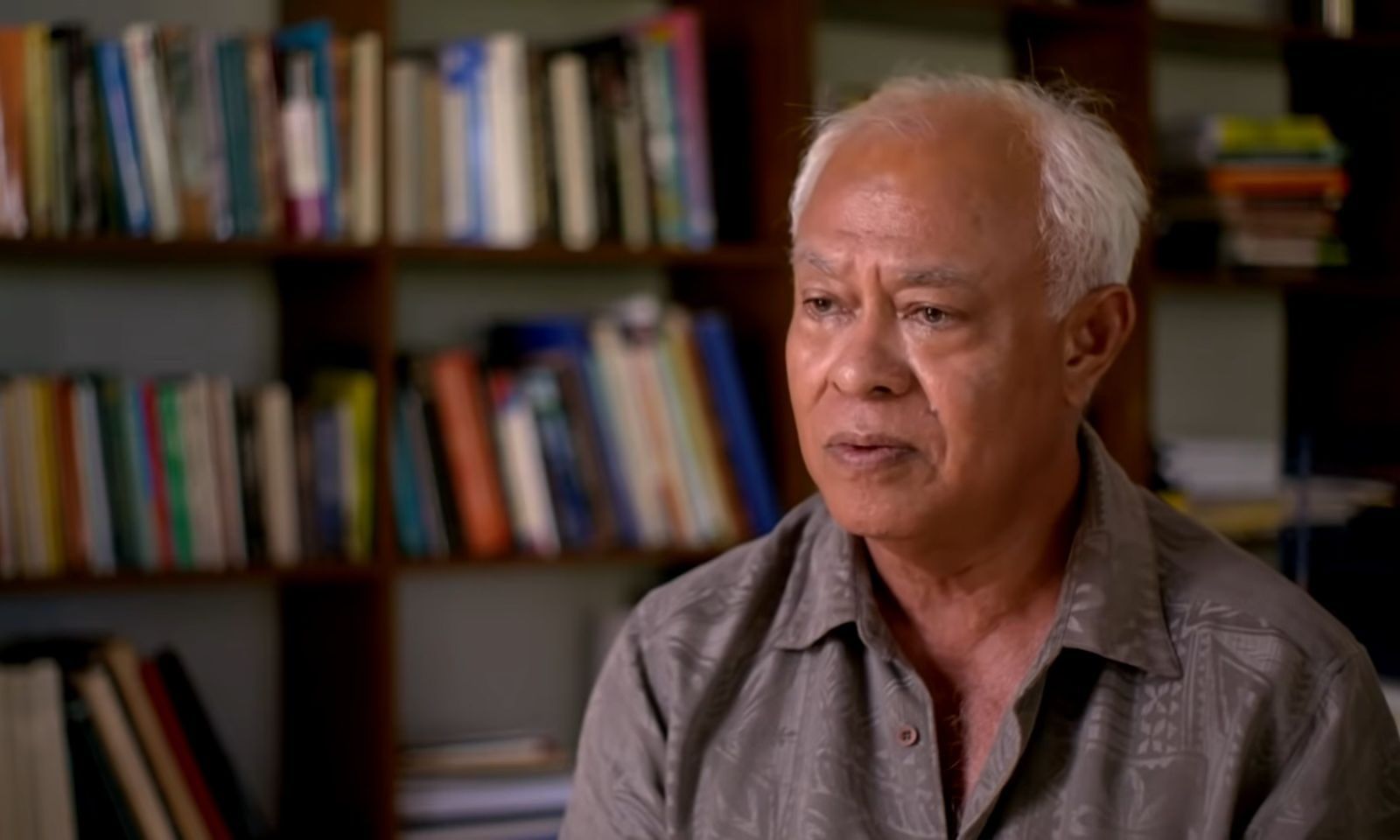

The author of O Tama Uli, Leasiolagi Dr Malama Meleisea explains in the documentary Tales of Time - Tama Uli that the German occupation exercised blackbirding.

He says this illegal recruiting process exploited up to 100,000 workers who were segregated from the local Sāmoans who also looked down on them.

By the end of the German occupation in 1914 the workers were meant to return home but due to New Zealand's following invasion and consequential occupation they involuntarily remained.

Screengrab from Kightley's documentary of Leasiolagi Dr Malama Meleisea. Photo/YouTube: TheCoconetTV

Lemoa says researching around the history of this period that meauli was a descriptive term for a collective of people and that "it seems that the negativity and derogatory connotations derived from the colonial power of the day".

"Their colonising and narcissistic attitude determined how people were received. They were occupying village land and the labourers of the day were carrying out orders and that's where that tension occurred."

This enslavement coupled with a segregation from the indigenous peoples echoes the history of indentured labourers in Fiji, where colonial forces weaponise indigeneity by introducing racial and class hierarchies to sustain oppression.

Why are palagi revered by God?

Some have argued though that Sāmoans calling colonisers palagi in relation to Godhood is evidence of a racist lens.

"Again it's descriptive, it's the same notion [as meauli]," Lemoa says.

"Sāmoans assumed they were from the heavens hence palagi: The heavens that burst, the skypiercers, so that's how we got that word."

He points out the story of how the name Aotearoa, or the long white cloud, came to be. He says similar to Sāmoans it's a descriptive notion, where if the sky was clear that day then Kuramārōtini may have named Aotearoa something completely different.

The distinction between Pacific naming conventions and western ones

Similar to Māori, Sāmoans traditionally identify with villages and chiefs going back hundreds of years rather than state identities like Sāmoan or New Zealander. Whereas in western culture, it's more common to homogenise a people and a country.

As we've seen over time Sāmoa learned more about the world since the early 1900s. Transliterations would then be adopted such as saina for Chinese and inkia for Indians, in line with western labelling.

Lemoa says saina has updated to asia, a learning curb due to saina being inappropriately used for any Asian and not specifically Chinese.

Furthermore, the Solomon Islanders today are referred to as Solomona, where even the name Solomon is a non-indigenous biblical reference.

And when it comes to meauli, particularly for those in the diaspora, it has merged with colonial constructs, which is why some continue to use it only for darker-skinned people and, sometimes due to language disconnection, not much else.

Sāmoa's relationship with colour and complexion

Another element in understanding the differences between an indigenous lens and a colonial diasporic lens is the importance of uli to Sāmoa.

Lemoa says colours are sacred to Sāmoans due to the night's connection to the sacredness of spirits, ancestors and God.

"People would always say o le mamalu o le pō, [with the word] Mamalu meaning that it's sacred or holy.

"It's a time when things are about to rest so you don't move in the night.

"The night is to know that people rest but our ancestors protect us. So in that sense pō o uli."

Lemoa also says a male having a darker complexion is a sign of his tautua (service) towards his village because it's the result of him actively tending to the plantation.

He says that that complexion is acknowledging how a person's efforts that may go unseen at the forefront shouldn't be undervalued.

Lemoa also says using black ink for tatau (tattoos) is a choice of intention not scarcity of inspiration, considering Sāmoa is surrounded by a blue ocean, red skies and green flora and fauna.

"We still try to go for that black ink. Once upon a time there was a whole sacred process to do it.

"The ink was hung over 14 years because once a male is born the ink is set up and preserved. By the time it's ready that male will go through the rites of passage of a tattoo."

Lastly, Lemoa points out tatau and tautua holding intentional symbolic importance to darkness extends further.

"If you look at our siapo mamanu (tapa cloth) it's black. Our original fale is black. When the thatched leaves turn from green it goes dark brown.

"There's a purpose behind those things."

Retiring the term meauli

For Lemoa he says he won't tell others what to say but implores people to "think before you speak".

"The term meauli to me is not a racial comment but it does have negative connotations if it's used in that manner.

"If we are using it for its negative connotations then again for Sāmoans that goes against our Christian and cultural values that doesn't honour the vā.

"I strongly advise if we hear the term that we think before we react. The whole context plays a huge factor of any setting and situation."