A new report says the first five years of a child's life forms a blueprint that shapes their whole future.

Photo/ Supplied

Think tank report reveals the importance of investing in a child's first five years

Experts say significant investment is needed from a child’s conception to starting school to change outcomes.

Government’s crime stance conflicts with housing cuts - expert

My Perspective: Should NZ start treating Pacific nations like partners and not dependents?

Cook Islands Prime Minister slams NZ aid freeze as ‘patronising’

Government’s crime stance conflicts with housing cuts - expert

My Perspective: Should NZ start treating Pacific nations like partners and not dependents?

A new report looks at ways to reverse intergenerational disadvantage and inequity in New Zealand.

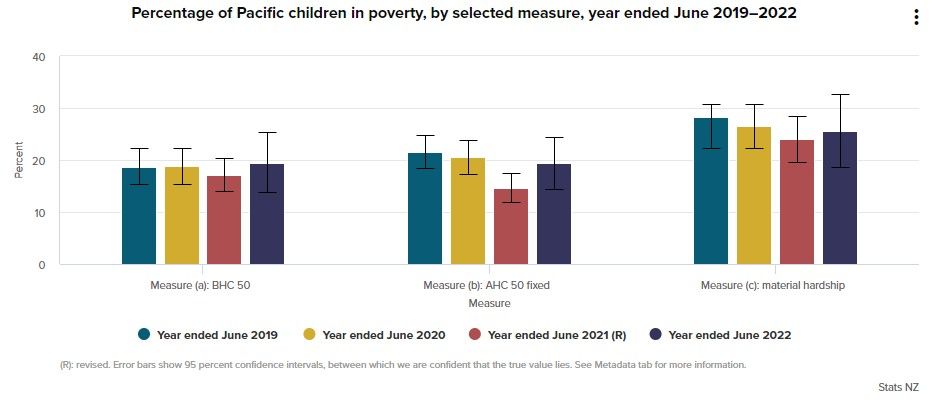

Up to three in 10 children are living in poverty, with Pacific and Māori children over-represented in those figures, according to the Early investment: A key to reversing intergenerational disadvantage and inequity in Aotearoa New Zealand report

The research, which has been published by the independent think tank Koi Tū: Centre for Informed Futures, lays out a brief for boosting funding for children and maternity services to stop the cycle of child poverty and disadvantage.

Report co-author Dr Johan Morreau says the first five years of a child’s life are crucial, where experiences can form a blueprint that shapes their future and that of their children.

“Whenever I see a young mum talking and laughing and playing with her baby, there’s a million neurons that she’s just introduced into this little person’s brain.

“If a child grows up in a hugely stressed environment, then that impacts their neurodevelopment. It impacts the parents’ ability to give them time, to give them love, to grow their little brains.

“And if a child grows up in that environment and doesn’t have the necessary development that enables them to function well socially, then that impacts that child’s ability to then parent.”

Despite measures to combat child poverty in recent years, the disadvantages felt by Pacific and Māori populations are still represented in the worst statistics.

“It has occurred against the backdrop of New Zealand’s colonial history, which has contributed to significant unacceptable disadvantage and inequity for Māori”, says Morreau.

“Children born into deprivation from the late 1980s were seriously stressed and are now the cohort of new parents whose children are also at greater risk of a continued cycle of disadvantage.”

The report lists contributing factors to the current picture; economic policy changes in the late 1980s, the removal of the universal family benefit, and less funding for home-visiting services like Public Health Nursing and Plunket.

Pacific poverty rates in the past three years. Photo/Stats NZ

Protecting brain development - a gamechanger and moneysaver

Morreau is a retired general and community paediatrician and former chief medical advisor at Lakes District Health Board. He says largely unseen, neglect, abuse or exposure to stress can stunt a child’s development.

“This is the part of the brain that enables you to learn empathy, that enables you to have relationships, to learn to make friends, to make good judgments in your life, to establish self-control over your activities so that you learn not to overreact to things that are minor.

“If you haven't learned those, you’re much more likely to end up in prison, you’re much more likely to fail in the education system, struggle with having friends, you're more likely to end up with wider health issues, mental health issues, so the whole thing is compounding.”

He admits this isn’t for all cases, but says having one adult in a child’s life who is besotted with them, can sometimes be all it takes to change their outcomes.

“These issues don’t impact every child, but when a child emerges through the system I find myself thinking, ‘I wonder who was there for that kiddy in those early days', who was actually there, growing that little influential brain, providing them with the love and the nurture that they needed.”

Morreau is urging the government to invest in children now, to save money further down the track.

“For every $1 of government spending, the return of investment is somewhere between $7-8 and $17-18, depending on different analyses, but it’s an absolute no-brainer, whether you look at it compassionately or economically.”

The report says support needs to kick in as soon as a pregnancy is recognised, with bolstered access to health, education and social development providers throughout the next five years.

Watch an interview with Koi Tū: The Centre for Informed Futures' Dr Felicia Low below: