Campbell University maritime history associate professor Salvatore Mercogliano says many critical issues remain unaddressed.

Photo/Campbell University and File

Questions remain about Manawanui shipwreck - expert

Maritime historian Salvatore Mercogliano suggests the sinking may have been caused by a lack of training.

Māngere-Ōtāhuhu's future leadership revealed for 2027

Second Apology: Fijian artist’s bold new film demands more for Pacific communities

Māngere-Ōtāhuhu's future leadership revealed for 2027

An American maritime historian says more information is needed following an inquiry into the sinking of the HMNZS Manawanui.

It has been two months since the New Zealand Navy vessel ran aground and sank off the southern coast of Sāmoa’s main island, Upolu, causing damage to the reef and raising concerns about the potential leak of 950,000 litres of fuel.

Last week’s interim report from the Court of Inquiry cited human error as the cause. However, Campbell University maritime history associate professor Salvatore Mercogliano says many critical issues remain unaddressed.

"They wanted to say right off the bat it was human error, but I do think there's a lot of issues as identified, including training, readiness.

“And [with] the type of ship that Manawanui was, a converted vessel from being used in the North Sea, it has a different system of propulsion and steering, an azipod system, so I think there's a lot more than what we got so far from the initial report.”

The ship had been conducting a coastline survey for 22 hours when it sank, but Mercogliano said the report needed to clarify who controlled the vessel when it struck the reef.

Watch Salvatore Mercogliano's full interview below.

“We know there's three people up on the bridge. We don't know who they are.

“Was this a watch officer, in other words, a junior officer who was standing watch? Were there senior officers up on the bridge, the ship's captain or the executive officer?

“How much training was done on the autopilot system and shifting between controls so that the ship's crew can do this without thinking so it's just pure muscle memory.”

Operator error or lack of training?

In an interview with William Terite on Pacific Mornings, Mercogliano said autopilot was often used for precise technical tasks, such as surveying, and questioned whether it was functioning correctly.

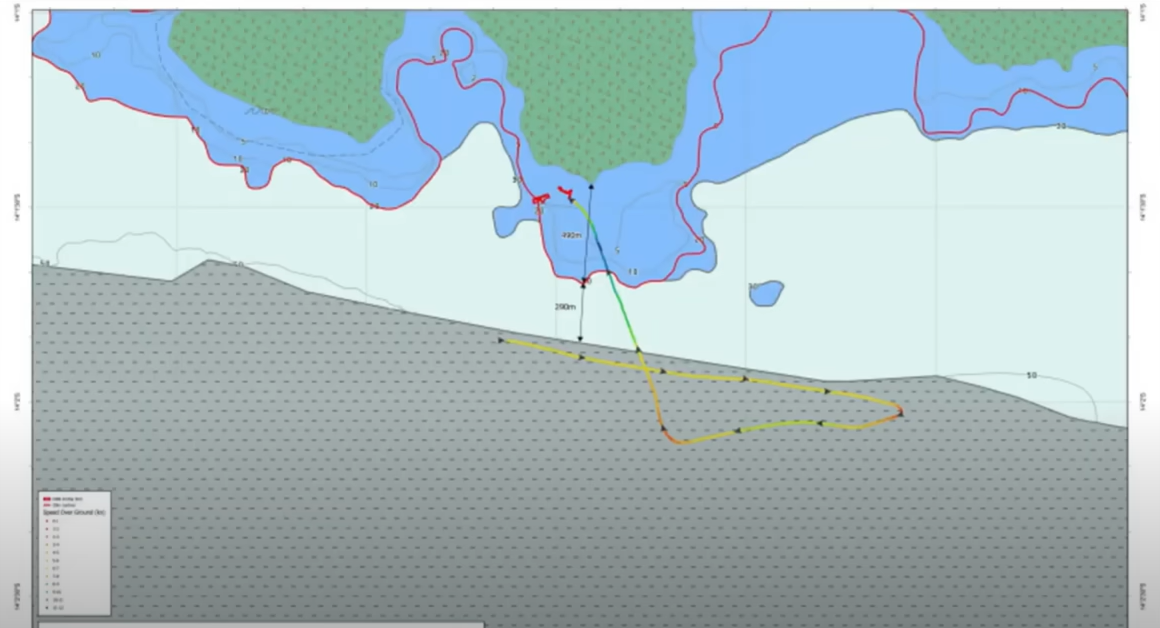

“The ship was heading eastward, and they had to swing back around, and they took the ship off autopilot to manually steer it, then they made another course turn, put it back onto autopilot, and then didn't realise they were on autopilot.

“I think the most disturbing element in the entire report was an indication that they thought they were slowing the vessel down by turning the propellers around and actually backing down, but what they wound up doing was actually giving more thrust to the ship and actually sped up from six knots to ten knots (11-18.5 kilometres per hour).”

The path of the Manawanui shows abrupt turns. Photo/What is Going on With Shipping screenshot

Mercogliano has consulted with ship classification societies, which oversee the construction and commissioning of vessels, and raised concerns about whether the crew received adequate training for the system they were operating.

“When the Royal New Zealand Navy purchased the vessel, they didn't get the full dynamic positioning system, the bells and whistles autopilot system that was originally on the vessel.

“Instead, they adopted a different system, and I have a question about what type of system they were using on board. Was it similar to ones that are on other Royal New Zealand Navy vessels or was it unique to the Manawanui?”

Mercogliano said the interim report presented by Chief of Navy Rear Admiral Garin Golding was damning and presented a wider issue in maritime operations.

“All militaries, all navies and shipping around the world are dealing with issues of funding, they're dealing with crew shortages, it's becoming much more difficult to get people to go on ships and sail over the horizon.

“Doing a survey operation on the southern shore of Samoa, close to a reef, is a hazardous operation, you're taking a risk with a ship, was there enough due diligence being done by the crew and the ship's captain to ensure that the ship was operating in a safe environment?”

What happens now?

A tug and barge carrying salvage equipment have departed from Whangārei. The fuel extraction process is expected to take 20 days from 16 December.

New Zealand Navy personnel are monitoring the Sāmoa wreck from the air and the sea.

The inquiry is expected to conclude in February, after which a separate disciplinary process will begin.

Mercogliano expects Commander Yvonne Gray, the ship's captain, to bear significant responsibility.

“A ship's captain is ultimately responsible for what happens. Even if that ship's captain is not on the bridge when this accident happens, they are responsible for ensuring that the crew is familiar with the operation of the ship, that they're well trained.”

While there were no casualties from the sinking, Mercogliano said other mistakes have had deadly consequences, which should be a lesson.

“Rules in ocean shipping are kind of written in blood. You need accidents to happen for change to take place, and the most important thing is to learn from this to prevent a future accident from happening and ensure that the other vessels in the Royal New Zealand Navy and other navies around the world are operating in a safe environment.”