From left: PMN News political reporter ‘Alakihihifo Vailala hosts Polynesian Panthers Lupematasila Melani Anae, Tigilau Ness, and Rev Alec Toleafoa at the Ngā Kākano talanoa, held at Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland Museum.

Photo/PMN News/Mary Afemata

‘That’s not our story’: Polynesian Panthers reject TV portrayal

At Auckland Museum, the group's founders urged Pacific youth to reclaim their history through truth-telling, talanoa, and civic action.

David Seymour defends Pacific communities, calls for smaller and efficient government

Pacific DNA research could change how diabetes and obesity are medicated

David Seymour defends Pacific communities, calls for smaller and efficient government

Founding members of the Polynesian Panther Party have called on Pacific youth to engage in politics and reclaim their history, after rejecting the 2021 TVNZ mini-series The Panthers, as a commercialised distortion of their movement.

Party founders Lupematasila Melani Anae, Reverend Alec Toleafoa and Tigilau Ness, made up the panel for a Auckland museum Ngā Kākano series event Mana, Media and the Polynesian Panther Party Legacy of Protest on Tuesday. PMN Political Reporter 'Alakihihifo Vailala was the host.

In a packed but intimate setting, the panellists urged young people to actively use talanoa, education, and voting power to fight racism, protect their community’s authentic stories, and build a stronger political voice.

Lupematasila, who chairs the Polynesian Panther Party Legacy Trust, says the TV mini-series failed to share their true kaupapa.

The Panthers drama mini-series was produced by Tavake and Four Knights Film for TVNZ and funded by NZ on Air.

“It’s not our story,” Lupematasila says. “Good on them for making it, but we know that it's not our story. They have artistic licence, but our input wasn’t taken seriously.

“We looked through scripts, suggested changes, but they pushed ahead with their own agenda.

“Our platform, our activities - none of that was covered in any depth - their main themes were Muldoon and the policemen, and that’s fine. But that’s not our story.”

Lupematasila says they managed to depict one thing right. “The only probably accurate portrayal was me climbing out the window to go to the first meeting."

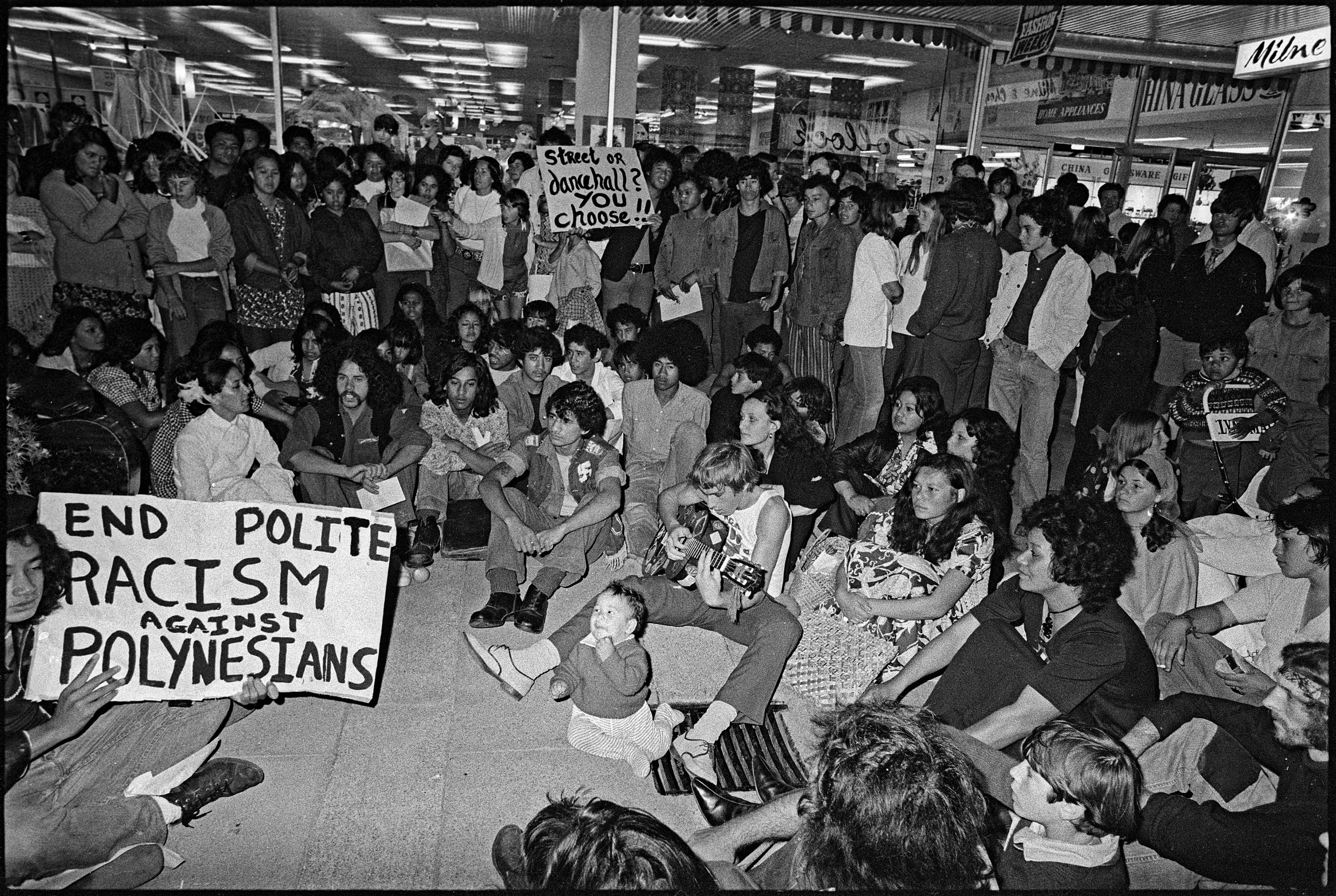

They’ve had to challenge the misrepresentation of the Polynesian Panthers as a gang - a stereotype reinforced by the mini-series - rather than the revolutionary social justice movement they truly were.

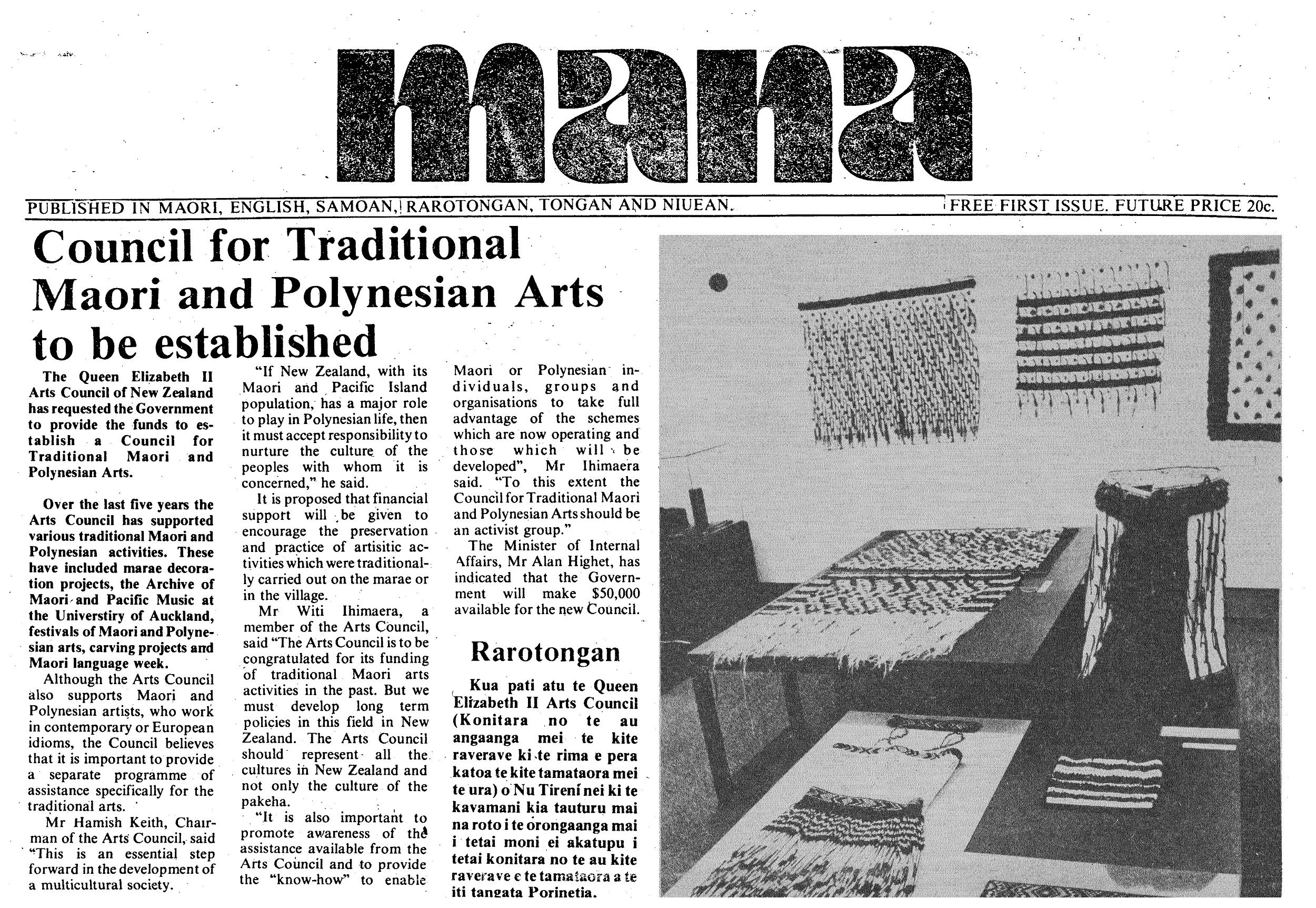

Mana Interim Committee (1977-1978), Mana, Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira. © Mana Interim Committee. Photo/Auckland Museum

“All of our Panthers couldn’t watch past the first episode,” Lupematasila says. “We’ve spent 20 years going into schools telling kids we weren’t a gang, then the show comes out, and all that work is undone.”

Toleafoa says the panel was approached about whether they would participate in the second series, and the producers were given a flat no.

“They wanted to talk to third parties and get the story second-hand, but out of respect for the Panthers, those third parties refused to comply,” Toleafoa says.

Joint Nga Tamatoa/Polynesian Panther protest about the closing of a near-by dance hall, popular with local youth. L-R seated: Hana Jackson; Morehu McDonald; Andre Rahman; unknown; Bruce Parr. 1972. Photo/John M Miller (Ngāpuhi)

“That’s why series two never happened…the story we’re hearing tonight is our story - that is our story.”

The event - Mana, Media and the Polynesian Panther Party Legacy of Protest - was part of the Museum’s Twilight Tuesdays series and tied into its Mana: Protest in Print exhibition.

The conversation highlighted how the Panthers relied on grassroots media to counter systemic racism and called on future leaders to do the same through civic action.

Instead of dramatised versions of their lives, the Panthers say truth lives in talanoa and print.

Polynesian Panther Party members and Auckland Museum staff gather following the “Mana, Media and the Polynesian Panther Party Legacy of Protest” talanoa at Auckland Museum on April 29. Photo/PMN News Mary Afemata

The Mana newspaper - launched in 1977 with multilingual stories by Pacific activists, including Ness - helped reclaim Pacific voices in a hostile media environment.

The Panthers' publications, such as RAPP and their legal aid booklets, also helped bring down arrest rates among Pacific youth.

“We had to print our own stories because the media wasn’t telling them,” Ness says.

“Those who translated and wrote - they were revolutionaries, even if they didn’t see themselves that way.”

Watch the Polynesian Panther Party reflect on 50 years of activism below.

Wayne Toleafoa, who served as the Panthers’ Minister of Information as a teenager, says getting their message out was a constant battle.

“We’d get our publications out wherever we could - but they’d edit everything,” he says.

“We were trying to show people we were non-violent - we were organised, but racism filtered everything.”

He says the wider public refused to believe what the Panthers were exposing about police harassment and state abuse.

Visitors explore the Mana: Protest in Print exhibition at Auckland Museum, which highlights the power of Pacific activism through grassroots media, print, and protest. Photo/PMN News Mary Afemata

“Even when we reported on real events like street checks or kids being picked up for no reason, people didn’t believe us,” Toleafoa says.

“It wasn’t until more and more Pacific people came forward that it started to shift.”

The talanoa made clear the Panthers were not just fighting street racism, but challenging institutional harm embedded in policy - from housing to policing, welfare and education.

Ness reflects on the racism of the era, saying Pacific youth were routinely targeted by police for statistics and quotas.

The Mana: Protest in Print exhibition at Auckland Museum showcases Pacific-led resistance through print, featuring publications like Mana, RAPP, and other grassroots media that amplified the voices of the Polynesian Panthers. Photo/PMN News Mary Afemata

“Today we know for a fact that the majority of Māori and Pacific Island youth were being picked up for statistics, police quotas,” Ness says.

“As a young person, I often wondered, where are they going, and why? Now we find out where they were going - welfare homes and eventually prisons, but at the time, nobody cared.”

Lupematasila says youth today must continue that legacy by voting and holding decision-makers to account. "It's more than that.”

“In Sāmoa's case, it's 100 years of persecution by the New Zealand administration and the distrust we have of governmental administration.

Mana Protest in Print exhibition at the Auckland Museum. Photo/PMN News Mary Afemata

“That's why we don't vote, that's why we don't even fill out questionnaires like the Census, because we've been hurt in the past by those administrative processes."

She adds civic protest means showing up, not just marching, but voting.

“The hikoi about Te Tiriti was a good example,” Lupematasila says. “The next big step is for that hikoi lot to register and vote - that’s real activism.”

Young people often ask how to become activists, and she says the answer starts at home.

Donna Awatere (second on right, with sign) and fellow activists protesting the visit of an American nuclear submarine, 1979. Photo/John Miller.

“We get asked in schools, How do I become an activist? The brothers say - ‘start by cleaning your room when your mum asks’.”

It’s about discipline, service and cultural grounding, she explains.

“We wear many hats - when we’re with our communities, we wear the fa’aaloalo - respectful hat, but in learning institutions, our hat is to be critical.”

Lupematasila reminds Pacific communities that representation is not enough.

“Just because they’re brown doesn’t mean they’re going to be good,” Lupematasila says.

“We want people who are passionate about change, no matter what party they’re from.

“Politics is one line of representation, but I’m saying - is it providing action? Is it providing change?”

She reflects on how the Panthers were dismissed in their time, even by their families.

Ka whawhai tonu mātou. Mana whenua occupy Takaparawhau Bastion Point, 1985. Photo/John Miller.

“Some called us activists. Some called us freedom fighters, and our own ‘āiga called us moepi - bedwetters.

“But we weren’t that. We were just kids standing up for our parents who were too respectful, too busy working, putting food on the table.”

Reverend Toleafoa says the Panthers chose non-violence not because they were soft, but because they understood the power of peaceful resistance.

“A true revolutionary is moved by great feelings of love for the people,” he says. “Violence solves nothing - our resistance was strategic.”

Mana newspaper. Auckland War Memorial Museum. HT1501 MAN. Photo/Auckland Museum

“Watching something like the Panther Series … you might want to know, is that really what happened? Go and find out,” Reverend Toleafoa says, encouraging people to be critical about what they consume.

As the event closes, the message for the next generation is clear: don’t let media define your story.

“You don’t need permission,” Lupematasila says. “If you care about your hood, surround yourself with people who care too - and get to work.”

Meanwhile, Reverend Toleafoa adds that the baton is now in the hands of Pacific youth. “Don’t let Netflix tell [your story] for you.”

LDR is local body journalism co-funded by RNZ and NZ On Air.